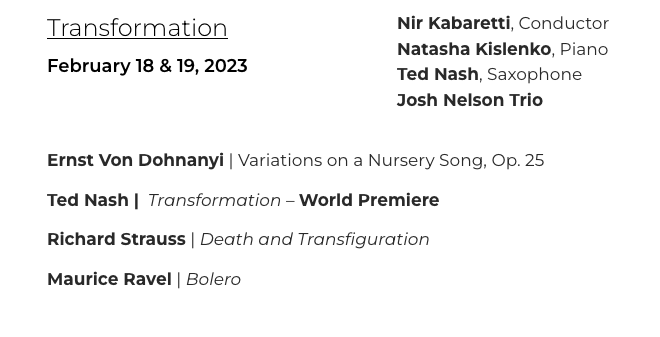

Santa Barbara Symphony on January 18-19 2025 - Mozart Marathon

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony website

Read Music and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti’s bio

Read violinist Jessica Guideri’s bio

Read flutist Amy Tatum’s bio

Read harpist Michelle Temple’s bio

Visit actor Tim Bagley’s website

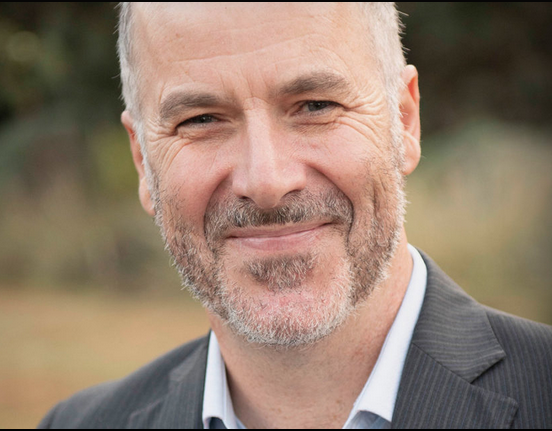

Read stage director Jonathan Fox’s bio

The Trouble with Marathons/Saturday, January 18, 2025

The Beauty and the Beast about marathons, particularly when they focus on a single composer, filmmaker, painter, architect, whatever . . . is curation. Curators, those tasked with selecting the content of an exhibition or performance series, can sometimes get a bit carried away, losing sight of the most important responsibility of the curatorial art; avoid at all costs, turning adventure and discovery into an awful bore.

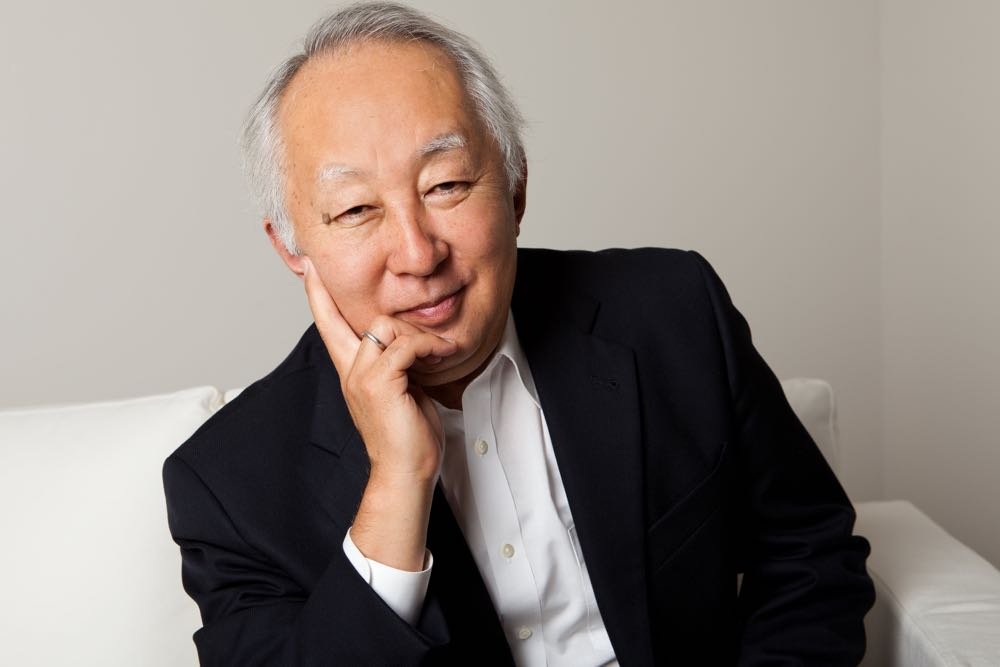

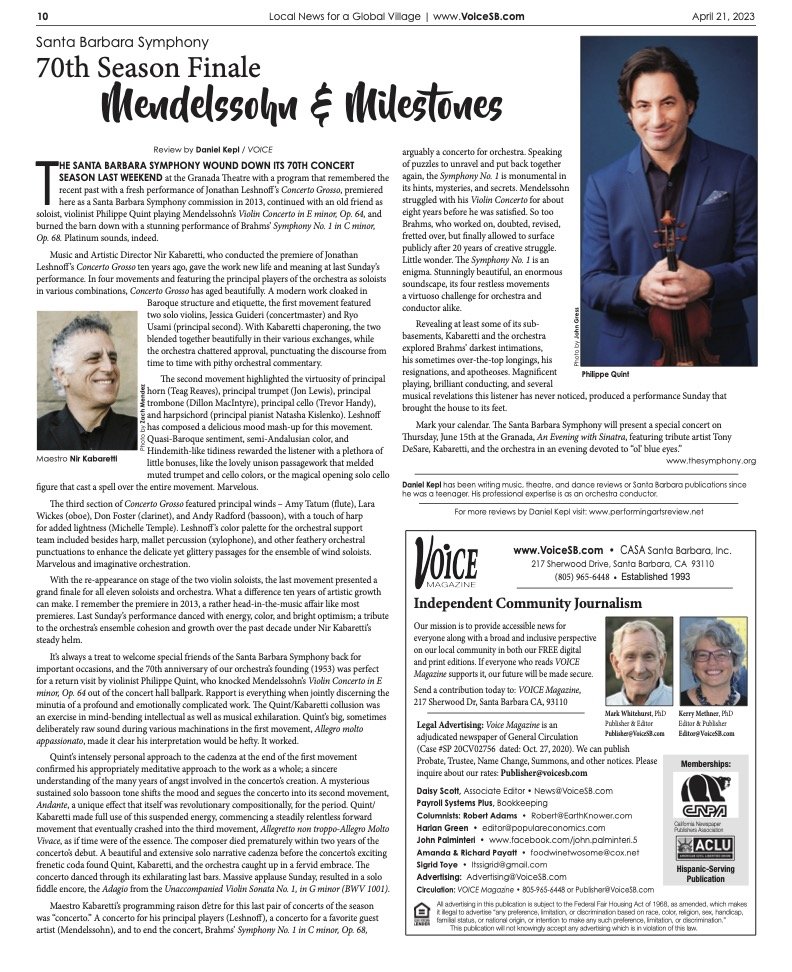

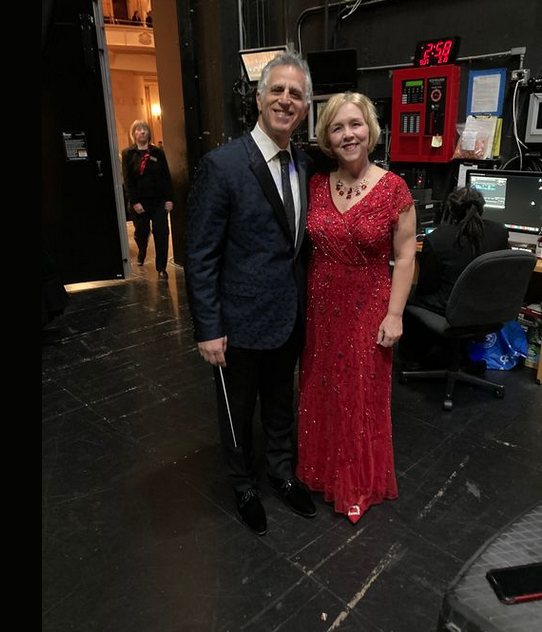

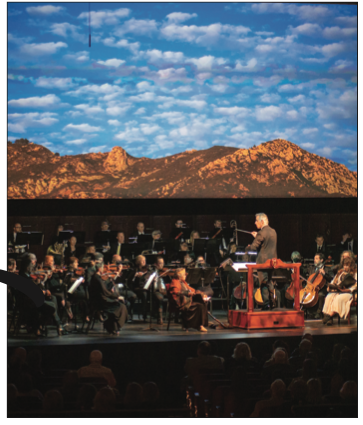

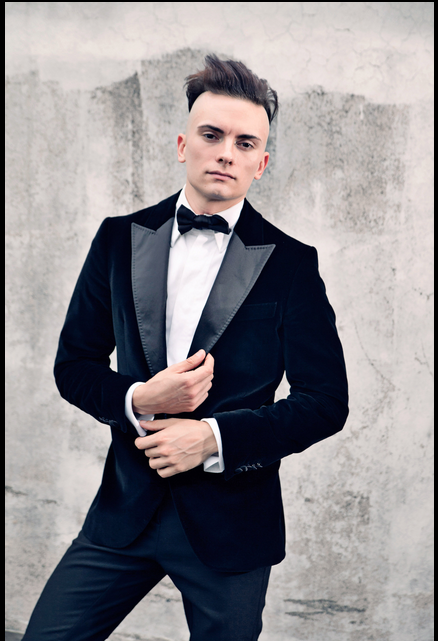

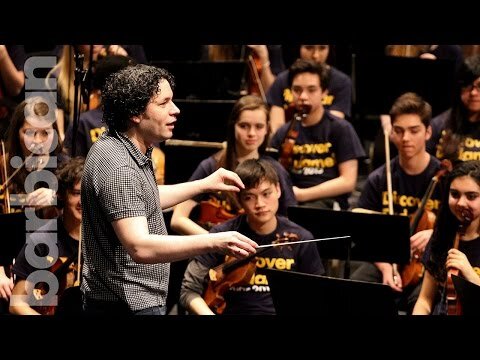

Santa Barbara Symphony audiences are fortunate. The curator-in-chief of music programming for the orchestra, Music, and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti is a master at conjuring fresh, beautifully imagined, and carefully crafted concert programs. Not the least flustered when tasked with creating two consecutive and separate all-Mozart programs for the orchestra’s January 18-19 concert pair in the Granada Theatre, Kabaretti chose to focus on the bright and playful side of Mozart’s complex personality, while also cleverly weaving a potent handful of narrative anecdotes into the fabric of the two concerts to gently separate the human being from the demigod.

Kabaretti’s programming architecture for the two Mozart concerts allowed for a satisfying and carefully calibrated flow from one piece to another, from Saturday evening to Sunday afternoon without a restless stir from auditors. Success was in balance, and aesthetic. The programs grazed Mozart’s copious oeuvre with scholarly magnanimity. An overture, a little night music, four concertos, and two symphonies were the ingredients for Kabaretti’s Mozartiana.

His spices? Forget savory. The tonalities filling the Granada Theatre for both concerts were in Mozart’s happiest key areas - C major, D major (lots of D major), and A major. Does curation, even of tonal centering matter? Of course! Two concerts over two days gave us a roomful of positive energy and, well, happiness. Did maestro Kabaretti think this magic up? Creativity and innovation are in his job description.

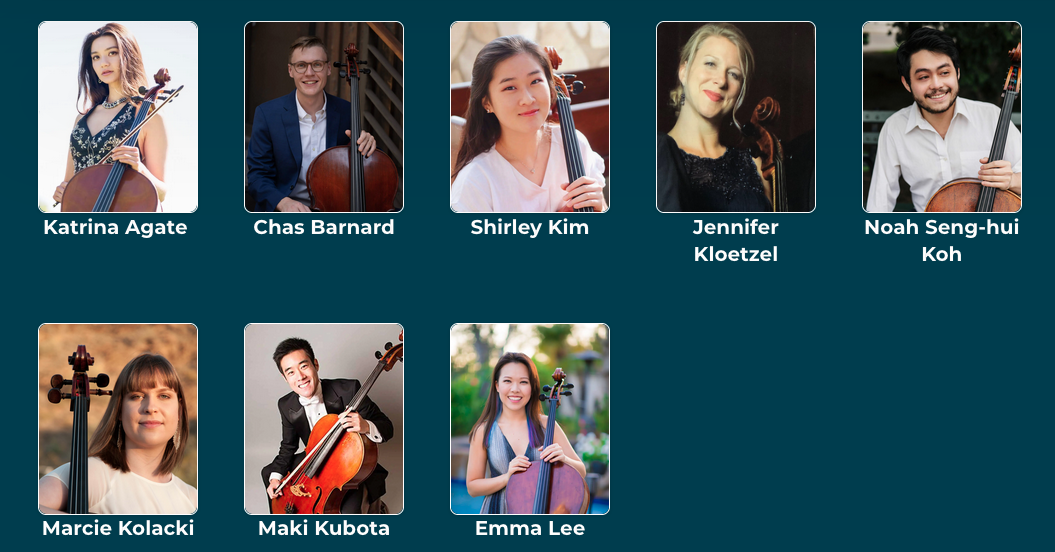

The concerto soloists for both concerts (more on each later) were the principal players of the SBSO. In southern California, with the Los Angeles megalopolis a little over an hour south, the SBSO principals also enjoy similar positions in the film and TV industry, and with many of the dozen or so professional orchestras, opera, and dance companies in the Greater Los Angeles area.

In other words, the Mozart Marathon concerto soloists were a collective treat to the ear; magnificent execution, authoritative styling, interesting cadenzas, and the confident virtuosity that comes with being at the top of one’s game.

It makes sense to open a Mozart Marathon with an overture. Without wink or nod but surely from intention, Kabaretti selected with straight face, the overture to Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario), a brief singspiel opera from 1786 commissioned for a private entertainment at the Vienna palace of Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II about the vanity of Italian singers. There’s more to the fascinating story. Think Salieri, and Google Impresario.

The Santa Barbara Symphony, tastefully reduced in string numbers to abide period performance practice, gave the roughly five-minute overture it’s stylistic due on Saturday’s opening night of the Marathon - clean articulation, spunky playing, lovely balances between departments, and an irresistibly glib C major temperament. A light confection to open the Mozart festivities.

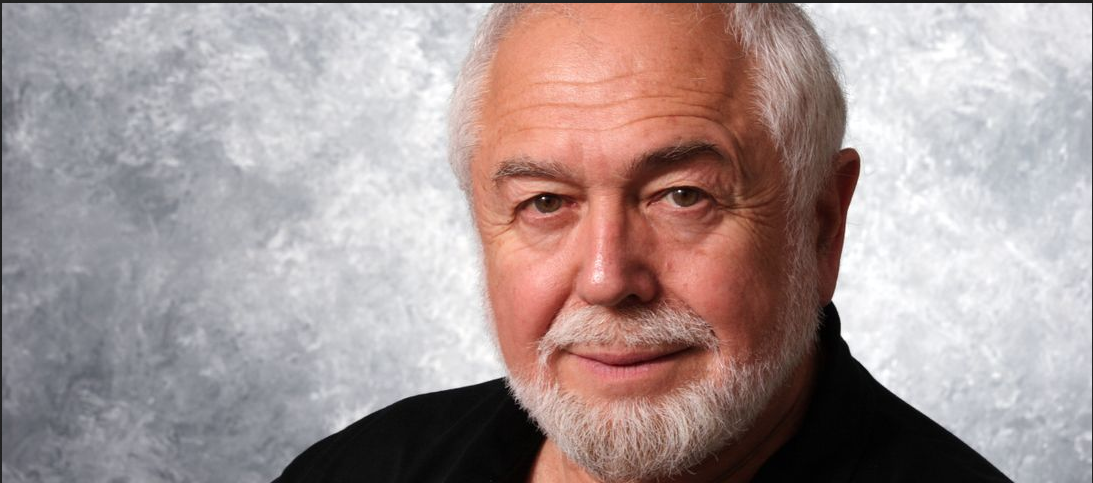

Kabaretti loves to collaborate with his colleagues at Santa Barbara’s other professional performing arts organizations. His relationship with stage director Jonathan Fox has been steady and productive over several years. Recently retired after 16 years as Artistic Director at Santa Barbara’s Ensemble Theatre Company, Fox has remained active as a freelance director for recent productions in Frankfurt and Cologne (Germany), Vienna (Austria), and Basel (Switzerland).

Having worked with conductor Kabaretti on several memorable concert/narrative collaborations pairing semi-staged dialogue to musical themes, Fox was a no brainer to join the Mozart Marathon creative team. Adding de-mystifying anecdotes about the composer as punctuation points to the extraordinary music, Fox devised a non-invasive narrative peek into the backstory of Mozart and his world.

Fox’s Mozart-as-Everyman story launched immediately after the Impresario overture on Saturday evening. Hollywood actor/comedian Tim Bagley (Will & Grace) entered the stage to read a scatological but fun letter from the young genius to his female cousin. After breaking culture and class stereotypes with a dose of Mozart’s delightfully descriptive potty mouth, Bagley reminded all what we were likely doing as ‘tweens (stomping in mud puddles was my favorite activity) while Mozart at the same age was touring Europe as a violin prodigy, composing masterpieces by the gigaton.

Saturday night’s concert continued in the same key as Impresario, a nice segue from one work to the other - the Concerto for Flute, Harp, and Orchestra in C major, K. 299/297c (1778). Amy Tatum flute, and Michelle Temple harp gave this classic of the repertoire a reading that was fresh as well as fascinating.

Amy Tatum, principal flute with Santa Barbara Symphony since 2023 plays all over the place including regularly for LA Opera, the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Pacific Symphony, Pasadena Symphony, New West Symphony, Los Angeles Master Chorale, and Long Beach Opera.

Michelle Temple has been principal harp with Santa Barbara Symphony since 1991 and for Pacific Symphony since 1994. She also serves as principal harp for Opera Santa Barbara, and undoubtedly gigs extensively throughout southern California, and beyond.

Out of the gate the two were pals in perspicacity, brushing a cobweb or two off this gorgeous and regularly performed work. The duo cadenzas they presented throughout the concerto were wonderful to enjoy (author?), because fresh to these ears. The lovely cadenza at the end of the Allegro for example, ushered the beautifully expressive Andantino into the soundscape, both artists enlightening the aesthetic with lots of dynamic contrast, subtly shaded colors, and pithy rubato.

After another wonderful duo cadenza, the two matching each other’s finesse equally, the last movement Rondeau-Allegro. Tricky this one, especially for the harpist. An aura of Mozartian playfulness was successfully conjured by the two, despite some busy pedal work on the harp! Breezy conducting from Kabaretti, and tight nearly gossamer playing from the orchestra closed a delightful first half of Saturday’s program in style.

After intermission, a brief return to the stage by Tim Bagley to enlighten the audience on the quasi-Oedipal, reasonably dysfunctional yet also loving co-dependency between Mozart and his father, Leopold. The narrative, which Jonathan Fox honed from source materials and letters was, in a canny coup de théâtre, the perfect setup for the creative if occasionally bruised fruit of this manager/artist, father/son connubial conundrum.

The Violin Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218 composed at the age of 19 in 1775 to use as a touring showpiece for himself along with the other violin concertos the young Mozart composed between 1773 and 1775 represents at a psychological sub-basement level, the pressure from the father to produce fresh material for tours, and the resultant brilliance unleashed from that parental pressure point.

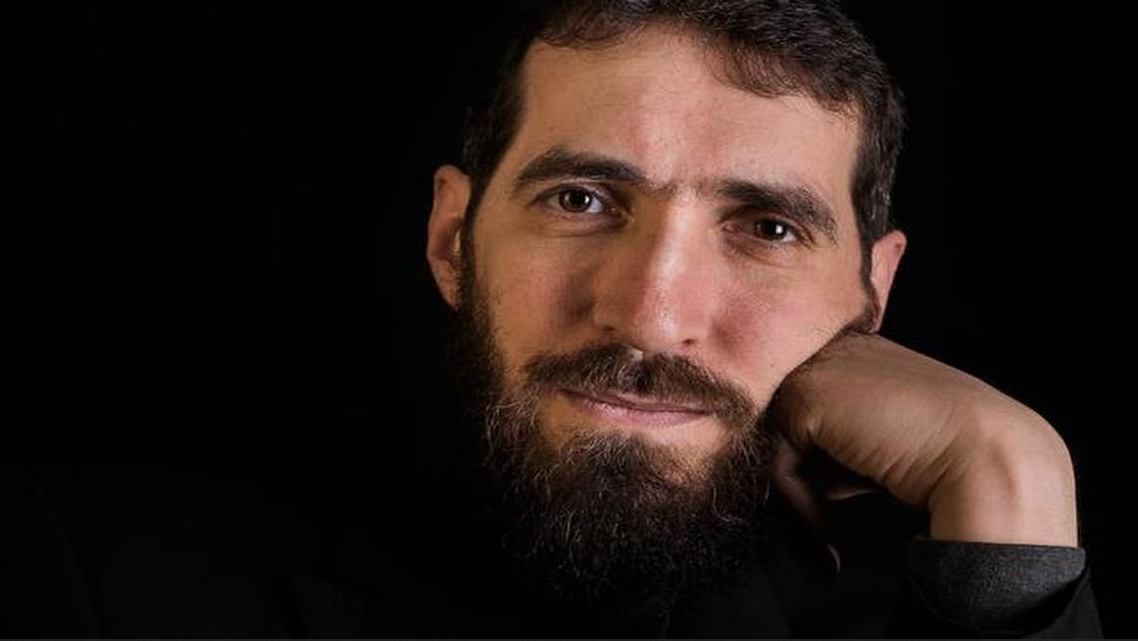

Another blockbuster performance was on tap. Jessica Guideri’s stunning interpretation of the work was as fresh and exciting as it gets. Concertmaster of Santa Barbara Symphony since 2015, Jessica Guideri has held principal positions with several orchestras including the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, Pacific Symphony, and Phoenix Symphony. Her Hollywood film and TV studio recording gigs indicate she’s at the top of the contractor lists for the best recording orchestras in the business.

Training and professionalism showed in her impeccably executed and innovative - fabulous and fresh cadenzas - interpretation of the work. Breathtaking articulation, pure, ringing tone production with superlative intonation, not to mention her significant palate of dynamic nuance, breathed life and rhythm into every movement of the concerto.

The first movement Allegro instantly cleared the air about where Guideri stands in the fiddle firmament. It could have been hallucination, but I swear Guideri deciphered, for that is what performing great music is about, a few things I had never heard before including perhaps, her unearthing of a prescient subconscious (Mozart’s) fragment in the first movement that reminded this listener for the first time of the composer’s coloratura aria for the Queen of the Night, Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen (Hell's vengeance boils in my heart).

It’s possible Guideri discovered and showed us a shard that might have grown in the composer’s mind over time, to be found fully developed years later in The Magic Flute (1791). Fresh discovery or hallucination, it doesn’t matter. The performance was revelatory.

The solo cadenza into the slow movement Andante contabile jumped off the page for this listener - a version I had never heard before. A fabulous choice of cadenza (there are many), which was modern in a Classic Period way, and fresh. The house listened in fascinated silence. Have I mentioned Guideri plays with authority and finesse? Her performance of the Andante cantabile was expressive certainly, but with added dollops of color and powerful but contained energy in super-soft passage work that electrified.

The last movement Rondeau: Andante grazioso - Allegro ma non troppo, one of the jewels of the violin concerto repertoire for its coy and youthful playfulness, was the more remarkable in this performance by Guideri. A stout if also playful performance, it was altogether genuine in temperament, thus engaging. The violinist gave us intellectual nourishment in spades, and also bathed us in her considerable elegance and style. Maestro Kabaretti and the orchestra gave back in kind.

To conclude this first of two ridiculously pleasant Mozart Marathon concerts, the Symphony No. 35 in D major (Haffner), K. 385 (1782). A work of Holy Grail-like significance and familiarity to orchestra musicians amateur and professional alike since, well, 1782, the Santa Barbara Symphony, Nir Kabaretti at the helm, offered a brisk and velveteen performance of its four iconic movements that was light, enthusiastic, candidly bracing, and completely satisfying.

Mariposa Series - JACK Quartet on December 7, 2024: Modern Medieval

Visit the Music Academy Mariposa Series website

Visit JACK Quartet’s website

Visit composer Taylor Brook’s Wikipedia page

Visit composer Vicente Atria’s website

Visit composer Juri Seo’s website

JACK Quartet: Modern Medieval - The Once and Future Micro-tonalists

We don’t often go into a transformative experience willingly. When it happens, the event wipes out distractions about oneself, immediate time, personal goals - the stuff of everyday conscious thought. Psychologists call it the “awe” effect.

An hour or more of evanescent whispers from sonic worlds past, present, and future conflated into a single musical riddle wrapped in 700 years of history, does not readily come to mind even for brainwave activists, as a wild night out on the town.

Wrong!

New York City-based JACK Quartet’s marvelously esoteric and thoroughly mind altering (no kidding) program on December 7 at the Music Academy in Santa Barbara - the second recital of the Academy’s 2024-2025 Mariposa Series - was also an utterly fascinating intellectual broadside.

Programmatic parable? Perhaps something about string theory, worlds in collision, and the oneness of all matter in the universe. Not bad for a Saturday evening adventure in music at the Music Academy.

In over 60 years of reviewing live concerts, it’s been my general policy to experience performances in the moment, without much if any preparation. I was not ready, therefore, to have neural surgery performed on my mindset by JACK Quartet’s profound thus a bit rattling, programming acumen.

Modern Medieval, a slightly disorienting, moderately oxymoronic program title on its face, was in fact a construct of bunker busting musical and cultural revelation. JACK captured the audience’s attention by means of sound sorcery, taking us on a journey through historical/musical time that set my head spinning softly in the moment, with long ruminations on the experience days after. How magnificent is that!

JACK Quartet - Christopher Otto violin, Austin Wulliman violin, John Pickford Richards viola, and Jay Campbell cello - have created together, in a burst of foursquare intuitive genius, a deceptively unassuming, quasi magical realist, and thoroughly satisfying touring program of new music inspired by Medieval compositional experimentation centered in Venice, which Nostradamus himself could not have prognosticated.

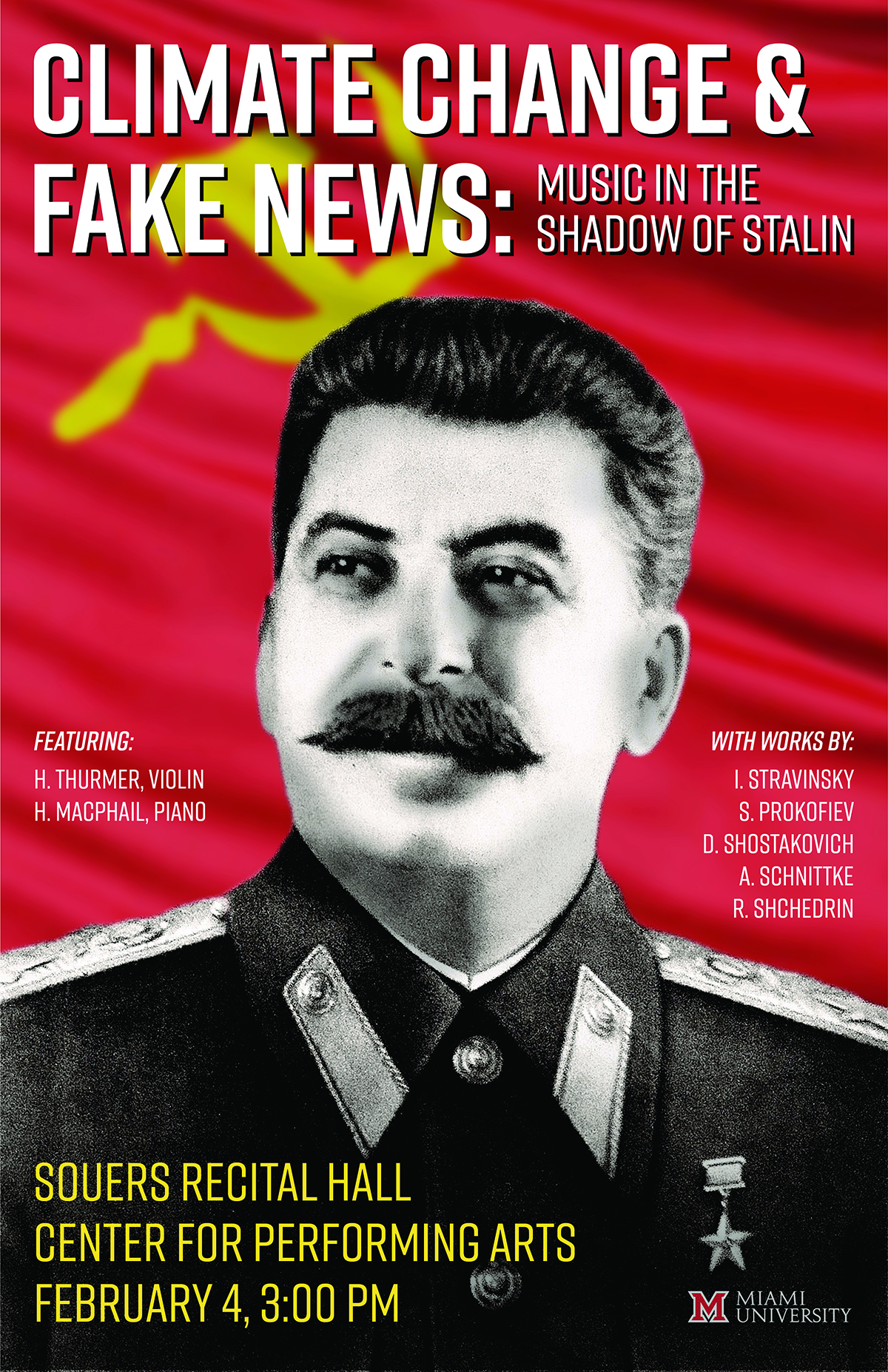

The program’s raison d'être was inspired by one of the most progressive composers of his time, Nicola Vicentino (1511-1576) who invented a micro-tonal keyboard instrument, the archicembalo, which should have earned him a burning at the stake.

Jack Quartet’s approach to unlocking the Rubick’s Cube of Modern Medieval is like dumping puzzle parts out of a box and asking the audience to put it together while sniffing chloroform. The “awe” kicked in immediately upon trying to figure out the program order itself. Lots of new voices.

Despite the pan-generational music history jigsaw JACK Quartet put before us, the great joy of the quartet’s meticulously organized Modern Medieval program was its mindful construction, which created an overall confidence among us auditors, at least subconsciously, that deep down in our synapses a re-wiring of thinking about music and history was in play, and we were going to be the beneficiaries.

The evening’s several seductions began with violinist Christopher Otto’s beguiling narrative before the first work was performed. Luring us down a verbal micro-tonal rabbit hole, a 700-year musicological dive upward from Medievalism to the present sound universe Westerners are generally accustomed to hearing while sedated at the dentist, the mind-melting message from JACK Quartet to its audience was simple, “Whatever is has already been, and what will be, has been before.” (Ecclesiastes 3:15).

JACK Quartet’s Modern Medieval program in a codpiece, considers the fight several hundred years back over which tuning method “just” or “tempered” would prevail in Western music. The quartet has a thing or two to say about the issue, it’s outcome then, and how things that go around, come around.

Pieces by Taylor Brook, Organum (2017) and Ars Nova (2017) served as programmatic bookends for the Modern Medieval thesis. His Phrygea, also composed for JACK Quartet in 2017 was slipped into the second half of the recital as a bonus. All three are contemporary homages to the bedrock forms and sounds of Nicola Vicentino and his free-thinking Venetian colleagues.

Organum prepared us for the musical soundscape ahead in whispering, languorously sustained whole tones. And as a kind of benediction at evening’s end, his Ars Nova hinted at the profundity of the 360-degree circumnavigation of time and musical process JACK Quartet had created and bestowed upon us.

The music in between those bookends consisted of three works tweaked for JACK by violinist Christopher Otto - Angelorum Psalat after Rodericus (2011/1390), Miserere after Nathaniel Giles (2023/1594) and Fumeux fume par fumee after Solage (2018/1390); with two works by Nicola Vicentino realized by JACK - Musica prisca caput and Madonna, il poco dolce (1555).

On the menu as well, JACK Quartet violinist Austin Wulliman’s fascinating 2024 composition for the ensemble, Dave’s Hocket; Vicente Atria’s hot off the press 2024 composition, Round-About; and Juri Seo’s Three Imaginary Chansons, also composed in 2024.

Suffice to say, the most satisfying aspect of JACK Quartet’s intoxicating program December 7 was not about individual pieces, though there were plenty of trophy winners in that category. Rather, the helium in the room was generated by a realization that sounds past and present were intermingling easily, as in a ghost story, reinforcing the idea of timelessness. Sounds discovered and explored in the Medieval period (micro-tonalism), were lost for centuries then re-discovered and deployed in our own age. How “woke” is that!

Memories from the vaporous daydreaming of the concert’s sound experience: colors and pitches deliberately skewed in dizzying but fun mashups; fascinating pitch clusters and tonal meltdowns; high harmonics creating “ghost” echos; rogue pitches splendidly informing the mystical wonder of sound.

Compositional highlights: Juri Seo’s Three Imaginary Chansons, particularly the last, Confronted Cocks and Running Dogs, Austin Wulliman’s Dave’s Hocket (one had to turn away, look to the ceiling to hear everything subtly taking place in the sounds), and Vicente Atria’s Round-About, with its energetic passage work and busy winks and nods to all kinds of things musical, modular, and multi-tonal, not to mention his powerful skills at writing for string quartet.

Daniel Kepl | performingartsreview.net

“I try to use words as I would sounds - I want them to have meaning and create visualization.”

JACK Quartet - Christopher Otto violin, Austin Wulliman violin, John Pickford Richards viola, Jay Campbell cello

PROGRAM

Taylor Brook, Organum (2017)

Christolpher Otto, Angelorum Psalat, after Rodericus (2011/1390)

Nicola Vicentino, Musica prisca caput - Madonna, il poco dolce (1555)

Austin Wulliman, Dave’s Hocket (2024)

Christopheer Otto, Miserere, after Nathaniel Giles (2023/1594)

Taylor Brook, Phrygea (2017)

Johnny MacMillan, Songs from the Seventh Floor (2021)

Christopher Otto, Fumeux fume par fumee, after Solage (2018/1390)

Juri Seo, Three Imaginary Chansons (2024)

Taylor Brook, Ars Nova (2017)

Composer Nicola Vicentino

Download a PDF of the review

Live performance photos by Emma Matthews

Composer Taylor Brook

Violinist/composer Christopher Otto

Violinist/composer Austin Wulliman

Composer Vicente Atria

Composer Juri Seo

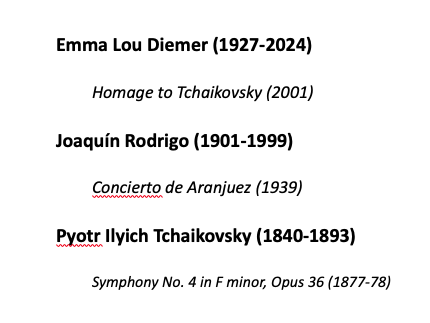

Santa Barbara Symphony on October 19, 2024 - Tributes and Triumphs

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony website

Read Music and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti’s bio

Visit guitarist Pablo Sáinz-Villegas’ website

Read In Memoriam: Emma Lou Diemer 1927-2024

Tributes and Triumphs

The special honor for most of us who knew American composer and longtime Santa Barbara resident Emma Lou Diemer (1927-2024) was the opportunity to bask even briefly, in the aura of her indefatigable energy. Like the sprawling prairie from which she came, the Kansas-born composer, who died here at 97 in June 2024, lived every minute of her time with us in happiness, joy, and a purposeful Somewhere Over the Rainbow optimism.

Tiny in stature, seemingly fragile as Delft though actually tough as nails with a side order of discipline, Diemer’s sincerely cheerful personality, her enthusiasm for just about everything, and most importantly her steadfast musical integrity, made her life and music a bright shining object in the classical music firmament. Diemer’s prodigious folio of works large and small are her legacy for us all to enjoy.

Music and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti and the Santa Barbara Symphony opened the orchestra’s 72nd season on October 19 at the Granada Theatre with a particularly apt tribute to Emma Lou Diemer’s creative compositional skills - a work of hers utilizing late Romantic orchestrations, like-minded ensemble balances and colors together with devilish-clever manipulations and melodic references to the composer being “homaged.”

Commissioned and premiered by the Santa Barbara Symphony in 2001, Homage to Tchaikovsky is a feisty concert opener of about six minutes. A perfect musical bon voyage to Emma Lou from her friends and musical colleagues in Santa Barbara, Homage bubbled with energy, pulse, optimism, and not a few winks and nods. Diemer’s playful tunes passed through various departments of the orchestra with sly accessibility and an unmistakably sassy American musical attitude.

Were bits of Tchaikovsky tunes present, however fractured, in Diemer’s compositional mashup? Honestly, I didn’t hear any in 2001, nor at this second opportunity on October 19, which is likely the point. Every time I convince myself there are no recognizable Tchaikovsky tune fragments in the piece, I see Emma Lou Diemer’s face looking down at me with that famously disarming twinkle in her eye!

The composer admitted in an earlier program note the piece was her first use of the technique of hiding fragments and other characteristics of one composer within a “fresh” composition by another. If themes from Tchaikovsky’s jukebox are there, hats off to Diemer’s skills at smoke and mirrors, the very object of the exercise. Kabaretti and the orchestra gave their own homage to Diemer’s genius with a performance that bristled with playful energy and technical expertise.

I remember my first encounter (it was visual) with Joaquín Rodrigo’s eponymous Concierto de Aranjuez for Guitar and Orchestra (1939). I was in high school (1963-1966) taking college-level summer classes at UC Santa Barbara. Exploring the Student Union building one day I found, running the length of a long interior hallway corridor, a seven-inch-high strip of colorful graphic art depicting in Schenkerian musical analysis style, a visual representation of the forms, structures, harmonic progress and resolutions of Concierto de Aranjuez.

I must stop by one day and see if it’s still there or painted over. In any case, that graphic and the time it took to create it speaks to the popularity of Rodrigo’s concerto over the decades since it’s premiere in 1939.

Like Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, most people have heard and recognize Rodrigo’s masterpiece, or bits of it. In both cases, the public might not know who the composers are, but can recognize the tunes. As career paths go, a composer can’t ask for much better.

Before the performance on October 19 by Spanish guitarist Pablo Sáinz-Villegas, who is a favorite guest artist with the orchestra, I had not heard the work performed in truly Iberian fado/flamenco (evocative/provocative) temperament - the key to its soul.

The concerto speaks with energy and rhythm of which it has plenty, but prior to Sáinz-Villegas’ interpretation, I had not experienced the sense of historical zeitgeist (Moorish conquest and removal) that informs Sáinz-Villegas’ sensibility. His psychologically piercing and genuinely authentic interpretation at so many levels, was a revelation.

The first movement Allegro con spirito, seemed at first quite straightforward, but it didn’t take long to realize Sáinz-Villegas’ performance was different from most - calm in execution, no drama. A meditative and appropriately melancholic performance that gave the movement new meaning and mysterious atavistic heft. Kabaretti and the orchestra obliged with incredibly sensitive collaboration.

The second movement Adagio, found Sáinz-Villegas in particularly magnificent expressive form, his playing regal, sophisticated, wildly expressive, while also superbly articulate; angst and joy commingling in a glory of sweet and savory irony.

During the solo cadenza before the last movement Allegro gentile, Sáinz-Villegas emphasized dissonant harmonics in a manner I’d not heard before - shocking, heartfelt, and meaningful. Powerful stuff. The audience received his charismatic playing with hushed obeisance, preparing perhaps unconsciously for the unfettered solidarity of technique and execution Sáinz-Villegas brought to the last movement itself.

His encore, Argentinian composer Astor Piazzolla’s Viva Tango in an arrangement for guitar and orchestra. Delightful.

Considering the moniker for the October 19-20 Santa Barbara Symphony concert pair was Tchaikovsky Immersion, there was little left for audience imagination than to experience one of the composer’s rip-snorting symphonies to close the evening with panache. Maestro Kabaretti, who has conducted the work on numerous occasions and knows it from memory, decided the composer’s Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36 would fit the bill. It did, handsomely.

With Kabaretti at the helm, and the orchestra an ensemble of professionals from Santa Barbara and Los Angeles who have played together for decades, it will cause no surprise to report the performance was stunning. With so many technical challenges in its four comprehensive and complicated movements, so much exposed section playing and unforgiving writing for horns to say nothing of the monumental arc of Tchaikovsky’s mighty vision, the No. 4 was the proverbial cherry on an evening of wonder.

Daniel Kepl | performingartsreview.net

“I try to use words as I would sounds - I want them to have meaning and create visualization.”

Conductor Nir Kabaretti and guitar soloist Pablo Sáinz-Villegas/performance photos by Nik Blaskovich

Download a PDF of the review

Camerata Pacifica recital in Santa Barbara on September 20, 2024

Visit Camerata Pacifica’s website

Visit violinist Paul Huang’s website

Visit pianist Gilles Vonsattel’s website

Visit cellist Santiago Cañón-Valencia’s website

Maurice Ravel - Sonata for Violin and Cello Claude Debussy - Images pour Piano, Book II Maurice Ravel - Piano Trio in A Minor for Violin, Piano, and Cello

The Synesthesiologist

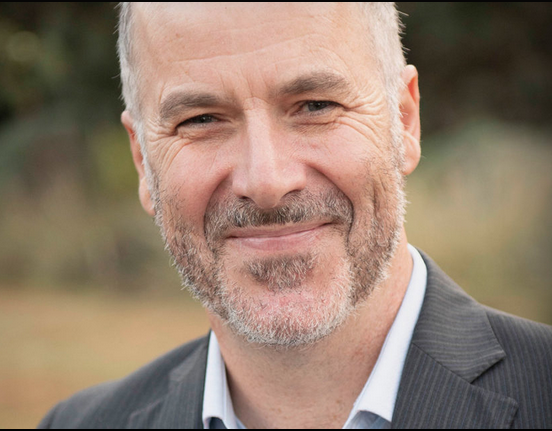

I’ve been attending and reviewing Camerata Pacifica concerts off and on since its first iteration as a chamber orchestra in 1990. Artistic Director Adrian Spence’s career project has morphed considerably over the past 34 years, especially after he moved the ensemble to its present Music Academy venue in Santa Barbara and added three more southern California cities to Camerata Pacifica’s sphere of musical influence - Thousand Oaks, San Mateo, and Los Angeles.

Spence re-branded the ensemble’s purpose and personnel early on and has nurtured lifelong artistic friendships with a broad roster of chamber music colleagues over the years. The result, chamber music of unquestioned artistic merit, emotional worth, and world class technical prowess.

Camerata Pacifica’s opening recital of the 2024-2025 season in Santa Barbara at the Music Academy on September 20th featured principal artists violinist Paul Huang and pianist Gilles Vonsattel, with guest artist cellist Santiago Cañón-Valencia. Music of Ravel and Debussy.

It was during this magnificently fragile and exquisitely realized French program I experienced a major Adrian Spence epiphany. I should have known Spence never fools around; nothing gets past his finely tuned brain. My revelation? He’s been pulling a Scriabin on his audiences for decades!

Synesthesia is a neurological condition and perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. For Russian composer Alexander Scriabin, sounds were colors and colors were sounds. The two were experienced as one.

Camerata Pacifica’s artistic director has been gifting his audiences with a synesthetic experience at his concerts. Call me callow for not seeing/hearing Spence’s serious messaging and thoughtful intent over the years.

Using a portable theatrical stage lighting rig at all four venues upon which to hang color-capable lighting systems as needed, Spence has created an AI event if you will, conflating sound and color for his audiences. Synesthesia indeed. Marvelous!

Beyond jumping out of planes for the rush of it Spence is not, I suspect, particularly into cheap entertainments. Choices about lighting each work in Camerata Pacifica’s musical portfolio over hundreds of programs, have been made with careful, intelligent purpose. Complimenti!

Case in point, Maurice Ravel’s Sonata for Violin and Cello composed during 1920-22 and dedicated to Claude Debussy (1862-1918). Bathed in subtly changing Monet blues throughout the performance, the sound/color effect was fabulously evocative. Violinist Paul Huang and cellist Santiago Cañón-Valencia communed together with stunning ensemble passage precision, gratifying sensitivity to musical coloration, and sweet, fragile harmonics; a superb performance of the first movement, Allegro.

The second movement, Très vif, with its fascinating pizzicato opening and pitch-perfect bowed ensemble playing between the two artists, was realized with Bartók-like intensity - very exciting.

The third movement Lent, which is the very soul of the sonata with its heartbreaking cello solo opening passage joined in mourning by the fiddle, was performed by the two at a shattering level of deep sensitivity - a duet of exquisite pain and sadness. A fabulous performance. The last movement of the sonata, Vif, avec entrain, brought the work to a balanced, dancerly finish - simultaneously ironic and fateful, with a little coda of pure exhilaration as the thrilling cherry on top.

Color hues in Emerald City greens lent pianist Gilles Vonsattel ample ambiance for his wizardly performance of Claude Debussy’s piano suite Images pour Piano, Book II (1907). Cloches à travers les feuilles (Bells through the leaves) with its pentatonic tonality and flowing, watery imagery, was executed by the artist in one delicious breath of fluidity.

Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut (And the moon descends on the temple that was) found Vonsattel in a state of superbly delicate and thoughtful meditation - a wildly intelligent interpretation, the lighting canvas easing into blues and mahoganies. Poissons d’or(Golden Fish), with its restless dashes of brilliant color and movement - the faster section of the piece a thrill of virtuoso technique - brought pianist Vonsattel’s segment of the program to an exhilarating close.

Ravel’s masterpiece from 1914 the Piano Trio in A Minor for Violin, Piano, and Cello brought this robust program of French masterpieces to a satisfying close. Bathed in soft woody lighting hues, Huang, Cañón-Valencia, and Vonsattel traversed Ravel’s 28-minute journey through four distinctly moody movements with a rich panoply of marvelous musical colors, delicate as confectioners icing.

The first movement Modéré was balance and intonation perfection, Huang’s tone color and technical control functioning splendidly in collaboration with his colleagues. No room for unconscious or frivolous playing from this crew.

Another pizzicato opening for the second movement Pantoum - Assez vif - Spence’s programmatic sensibility sparkling with intelligence - illustrated the joy and ease of Huang’s gorgeous playing in particular, while the third movement Passacaille: Très Large was just that - capacious and entirely bracing, with nearly painfully intense ensemble playing from the artists, an altogether engaging and moving experience.

The Finale: Animé featured Ravel’s innovative sense of orchestration, even for only three players. Begging the question, how can three people make so much sound, the performance was deliciously overwhelming.

Daniel Kepl| Performing Arts Review

Founder/Artistic Director Adrian Spence

Download a PDF of the review

blue hues for Ravel’s Sonata for Violin and Cello

pianist Gilles Vonsattel

browns for Ravel’s Piano Trio in A Minor for Violin, Piano, and Cello

violinist Paul Huang

Cellist Santiago Cañón-Valencia

the lighting cage - from an earlier recital

Time for Three joins Santa Barbara Symphony on November 18-19 2023

Performance photos by Nik Blaskovich

State Street Ballet and Santa Barbara Symphony make history: Giselle on October 21-22 2023

Visit the State Street Ballet website

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony website

An historic collaboration: State Street Ballet + conductor Nir Kabaretti and the Santa Barbara Symphony = a sublime full-length Giselle

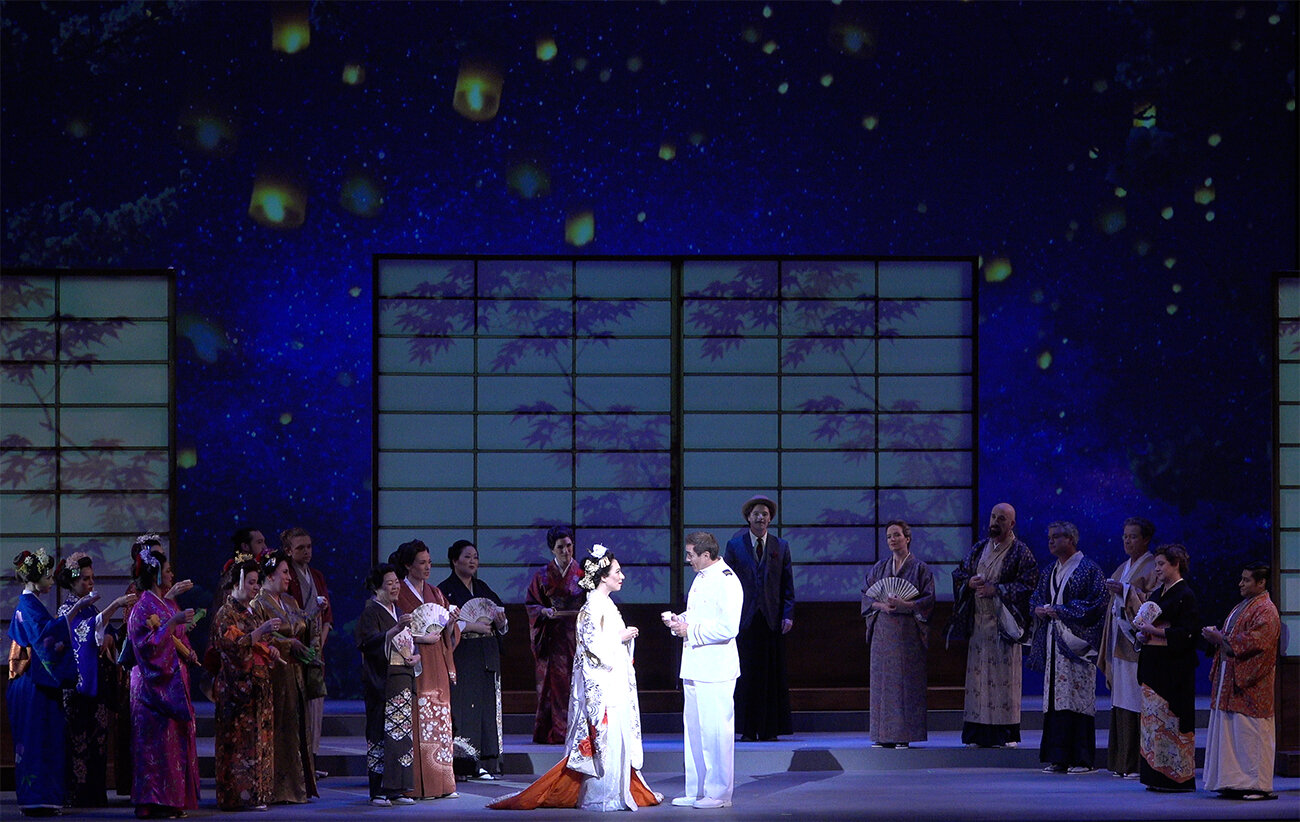

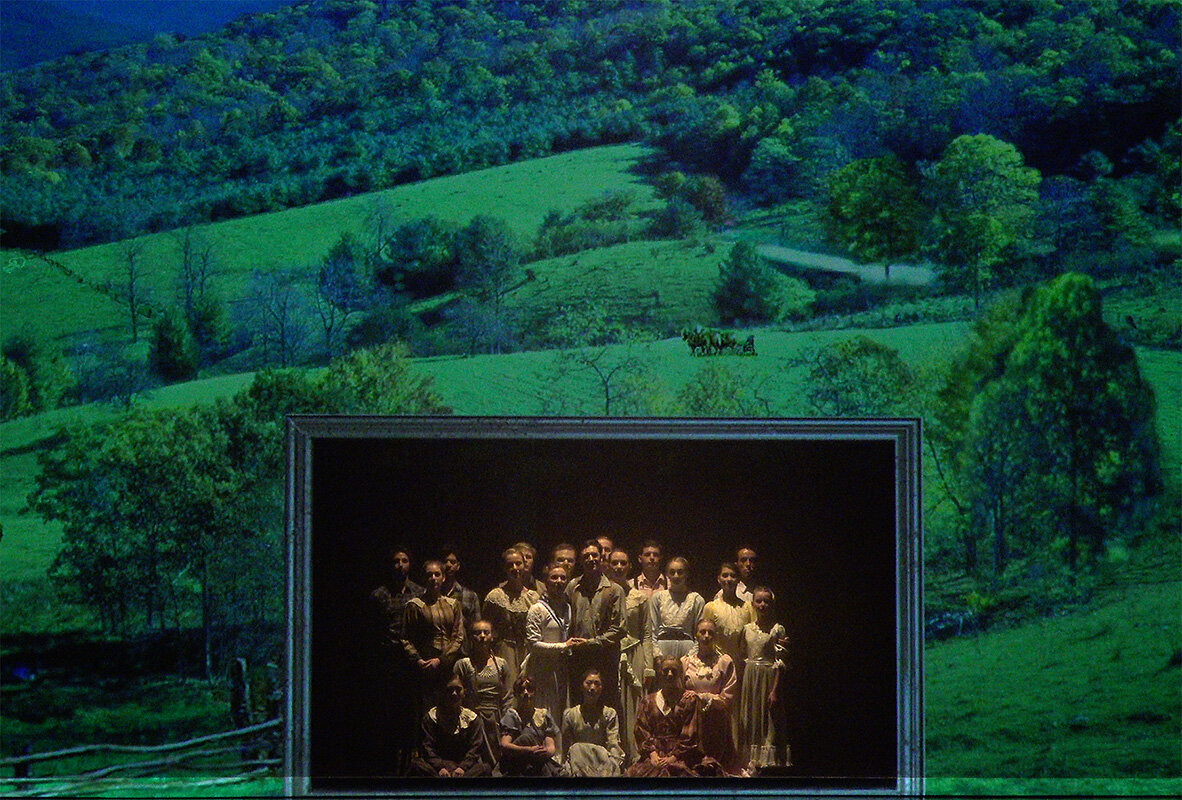

For the first time in the history of collaborations between these two major organizations, the Santa Barbara Symphony was in the Granada Theatre’s orchestra pit for State Street Ballet’s season opening performances on October 21 and 22 of Adolphe Adam’s full-length romantic pantomime ballet from 1841 Giselle, one of a handful of the most famous and virtuoso ballets in the repertory.

Music and Artistic Director of the Symphony Nir Kabaretti was at the helm in the pit, and the professional dancers of State Street Ballet under new Artistic Director Megan Philipp knew it. The company was more than up to the task, achieving a high level of artistry and execution, confident the maestro would have their back. The Granada Theatre was sold out for both weekend performances.

The Giselle performance on October 22nd was music and dance heaven, top to bottom. A delicate soufflé of great beauty requiring stamina as well as virtuosity. The entire company was inspired. The principal soloist’s bravura dancing and the corps de ballet’s precise articulation took everything up a notch from the company’s already high bar.

Professional confidence, both in the pit and on stage gave the performance a magical shimmer. Studious attention to mid-nineteenth century stylized mime, to say nothing of the stunning classical ballet technique on display was matched by music making from the pit besotted in emotional power and thrall.

This gorgeous conflation of two great organizations into one spectacularly focused artistic realization of Adam’s masterpiece powered a magical aura in the room, a nimbus that everybody felt on stage and throughout the house. Fireworks, balletic and orchestral was the order of the day. Set design, lighting and staging were also of extraordinary professionalism and subtlety. This production of Giselle will remain in audience memory for a long time – the very goal of live performance art.

No stranger to Europe’s great opera houses - Vienna, Madrid, Milan, Florence, Rome, and most recently the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm - maestro Kabaratti has conducted ballet as well as opera in these houses and others around the world frequently. Giselle has been in his repertoire for several years, and it showed. His ease with the responsibility, his confident expertise in executing Adam’s huge two-and-a-half-hour narrative arc of dance, music and drama was thrilling to watch and hear on the 22nd.

Buoyed from working with such an experienced ballet conductor, the dancer’s artistic self-confidence became beautifully empowered. The result on stage was more than usually exciting, often spectacular. The company’s expertise in executing this historic model of virtuoso classical ballet was clearly enhanced by the company’s trust in the conductor in the pit. Risks were taken, heights were achieved.

It takes two to tango, and State Street Ballet Artistic Director Megan Philipp crafted a superb curation of Adam’s masterpiece. Attention to choreographic detail was as breathtaking as Kabaretti’s conducting. State Street Ballet has refreshed itself in recent years, hiring exciting new talent and shaping its solo and ensemble discipline to a high standard. Giselle was the perfect season-opening showpiece for the company.

The original 1841 choreography for Giselle was created by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot. A slew of choreographers like Marius Petipa have tinkered with the original choreography since - high compliment. Over the years, Giselle has remained solid – the marvelous arc of its original Coralli/Perrot structure essentially unchanged.

The performance on the 22nd was gorgeous in execution thanks to skillful staging by Marina Fliagina, Chauncey Parsons, and Megan Philipp. Skill, flair, and the discipline of years of acquaintance with the work by the three colleagues paid off in superlatives. Nicole Thompson’s costume design was exactly what the music told us to imagine, abetted by Samantha Jelinek’s obliging lighting design, and the functional sets of Rolf Freeman, and Inland Pacific Ballet.

State Street Ballet’s principal cast were powerful acting dancers, their individual technique superb. Credibility in acting out one of the craziest stories in ballet history disarmed and was moving. Sometimes stunning to the eye, always a perfection of detailed classical ballet movement, virtuoso performances were turned in by all the principals to mind-boggling effect and audience delight. The nearly lost art of mid-nineteenth century mime was masterfully achieved by all with true Period elegance.

Breaking out Blasis’s Traité élèmentaire, théorique et pratique de l’art de la danse (1820) to describe in detail the encyclopedic footwork on display in Giselle would be exhausting. Suffice to say, Nerea Barrondo was one of the most touching and believable Giselle’s in this viewer’s memory stretching over several decades seeing the ballet in much larger cities. Her acting, demur and without affectation, her dancing delicate, fragile, deeply moving.

A finer Count Albrecht than State Street Ballet’s Ryan Lenkey would be hard to find. His stature on stage, his understanding of his character as Giselle’s almost lover, his mastery of the art of nineteenth century mime, and most importantly his believability made him a great Count Albrecht, and a solid asset for State Street Ballet. Lenkey has mastered the role.

Noam Tsivkin has been with the company since 2016 and created a character of high energy and determined resistance in his role as Hilarion, Giselle’s true love. Superb virtuoso dancing from Tsivkin was often breathtaking. Denise Grimm (Berthe), Tanner Blee (Duke of Courtland), Kaia Abraham (Bathilde), and Sergei Domrachev as Wilfred honored the provenance of Giselle with amazing character studies and solid dance virtuosity. Ditto Marika Kobayashi and Harold Mendez (Peasant Pas de deux), and a truly impressive State Street Ballet corps de ballet.

Download a PDF of the review

Theatre Group at Santa Barbara City College - Kate Hamill's Emma on October 13, 2023

Kate Hamill’s 2022 play based on Jane Austen’s last novel Emma, misses by a country mile

American actress and playwright Kate Hamill makes clear in her biographical material that when she adapts the novels of Jane Austen for theatrical presentation, 60% of the re-write is her own original material. Hamill’s boast proved uncomfortable on opening night October 13, 2023 as the Theatre Group at Santa Barbara City College presented her adaptation of Jane Austen’s subtly satirical, gently comedic, and seriously message-driven last novel Emma (1815). Playwright Hamill has turned Austen’s perceptive masterpiece into cringe worthy slapstick.

Director and instructor of acting at SBCC Theatre Arts Katie Laris set her company of student and adult amateurs an unnecessarily difficult task from the get-go by deciding to present the play in British English. The resulting mishmash of accents - questionably British, predominantly American, and otherwise unidentifiable – was regrettable. Dialects appeared and disappeared throughout the evening with the regularity of a pesky speech impediment.

Laris’ cast struggled valiantly but without much success to meet the director’s unnecessary language challenge when they could have presented the play far more successfully in American English. Playwright Hamill had, after all, turned the literary cheek by morphing Austin’s British masterpiece into American comedic schtick.

Co-chair of the Department of Theatre Arts Patricia L. Frank didn’t have much to do as Scenic and Lighting Director for Emma. Her lighting throughout the play’s two acts stayed pretty much ice cold bright, more-or-less unchanging and static - decidedly unimaginative. Her single set piece for the show, more Crusader castle than English country estate, begged the question - budget constraints?

Sound Designer Barbara Hirsch scattered credible period music samplers spanning a hundred years or so up to and around 1815 throughout the play, but considering Jane Austen was a well-known and gifted musician, Hirsch might have sought out popular pieces for fortepiano and voice (Austen sang too) from the Georgian Period; the tunes most likely to have been on hand and performed by wealthy amateurs at their country estate social gatherings (the motif for most of the play). A little research would have made for a more focused and interesting sound ambiance.

Stage movement and other blocking – the dance choreography for party and wedding scenes in particular – was an entirely improvised mess on stage - embarrassing. To her credit, Costume Designer Pamela Shaw achieved excellent results at assembling wardrobe with the look of the Napoleonic Period. Brava!

The cast for Emma - City College students with adult amateur actors from the community - needed much more artistic leadership than director Laris delivered. Lexie Brent who played the title role of Emma, was all over the map in her attempt to prod laughs from the audience. A little balancing by director Laris of these raw fluxes of temperament and accent would have redounded to Brent’s credit. Clayton Barry in the role of Mr. Knightley managed his English accent and improvised blocking with solid success – a job well done in a generally precarious ensemble acting environment.

Grace Wilson as Harriet Smith, and Jenna Scanlon as Miss Bates navigated their scenes together with rough-hewn but empathic finesse. Playing the vicar as a dandy - who came up with that one? - Mario Guerrero was permitted unfettered tastelessness as he improvised his way through a ballet of awkward moments on stage. His delivery? Indecipherable.

The character of Mr. Weston was imagined by Robert Allen as something between P.T. Barnum and Boss Tweed. At least Allen made no bones about speaking in gangster American English exclusively. A sensible decision. Anikka Abbott as Jane Fairfax, Emma’s perceived rival, managed to hold her own, despite apparently limited pedagogic help from faculty to understand at a deeper level, one of the most pivotal characters in Austin’s novel.

Luke Hamilton, who stepped into the role of the amiable young sex object and true dandy Frank Churchill, found himself also abandoned by leadership - un-coached thus uncouth in his understanding and presentation on stage of this crucial character in Austin’s novel. Other cast members – Van Riker as Mr. Woodhouse, Rachel Brown as Mrs. Weston, Lana Kanen as Mrs. Elton and a maid, and Sue Smiley as Mrs. Bates - pretty much sorted out character development on their own. It showed.

Playwright Hamill states her mission in adapting Jane Austen’s novels for the theater is about looking at Austen’s work through a 21st century lens, especially a modern woman’s perception of sexism, marriage dependency, independence, and self-worth. Jane Austen’s advocacy for women and their struggle for equal rights, the thematic subtext of all of her novels, was prescient in 1815 and more so today. Adapting her last and some say best novel for the theater is a noble project. Hamill has unfortunately missed the mark by opting for cheap laughs.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the review

Santa Barbara Symphony launches 2023-2024 season with Beethoven's Ninth on October 14 & 15, 2023

Enjoy my review of the Santa Barbara Symphony for VOICE magazine

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

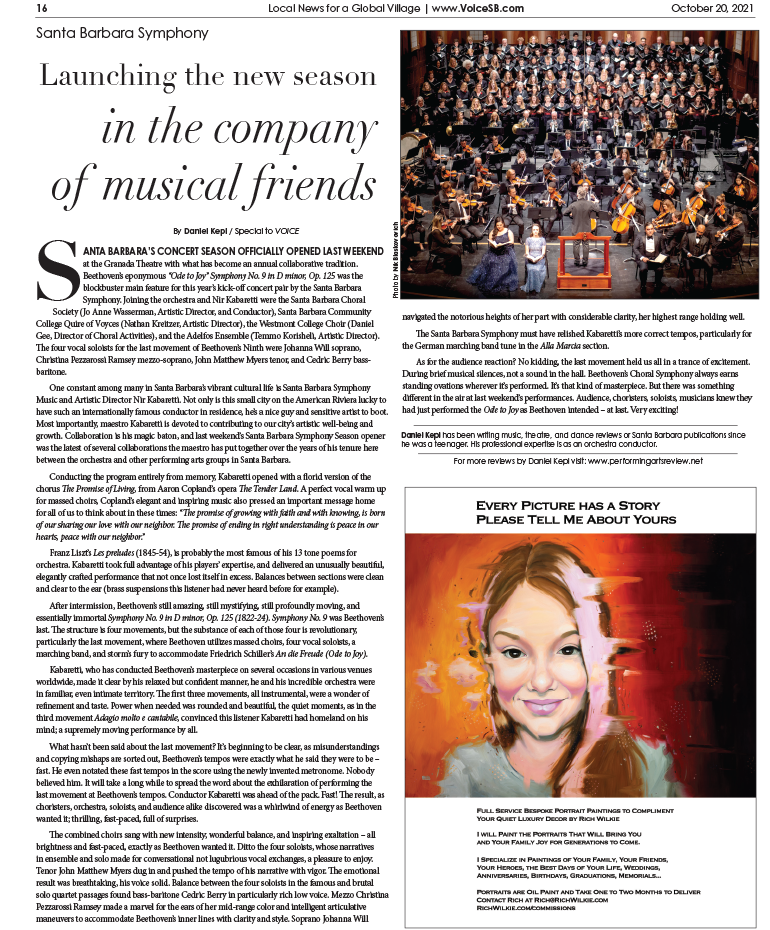

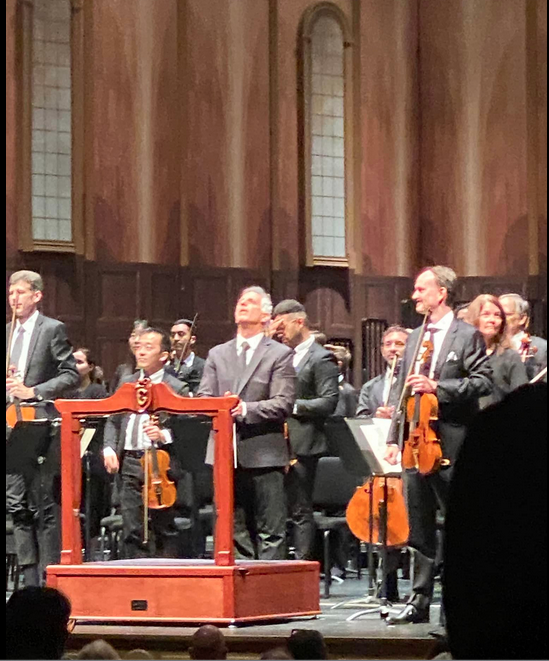

Launching the new season in the company of musical friends

Santa Barbara’s concert season officially opened last weekend at the Granada Theatre with what has become an annual collaborative tradition. Beethoven’s eponymous “Ode to Joy” Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 was the blockbuster main feature for this year’s kick-off concert pair by the Santa Barbara Symphony. Joining the orchestra and Nir Kabaretti were the Santa Barbara Choral Society (Jo Anne Wasserman, Artistic Director, and Conductor), Santa Barbara Community College Quire of Voyces (Nathan Kreitzer, Artistic Director), the Westmont College Choir (Daniel Gee, Director of Choral Activities), and the Adelfos Ensemble (Temmo Korisheli, Artistic Director). The four vocal soloists for the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth were Johanna Will soprano, Christina Pezzarossi Ramsey mezzo-soprano, John Matthew Myers tenor, and Cedric Berry bass-baritone.

One constant among many in Santa Barbara’s vibrant cultural life is Santa Barbara Symphony Music and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti. Not only is this small city on the American Riviera lucky to have such an internationally famous conductor in residence he’s a nice guy and sensitive artist to boot. Most importantly, maestro Kabaretti is devoted to contributing to our city’s artistic well-being and growth. Collaboration is his magic baton, and last weekend’s Santa Barbara Symphony season opener was the latest of several collaborations the maestro has put together over the years of his tenure here between the orchestra and other performing arts groups in Santa Barbara.

Conducting the program entirely from memory last Sunday, Kabaretti opened with a florid version of the chorus “The Promise of Living,” from Aaron Copland’s opera The Tender Land. A perfect vocal warm up for massed choirs, Copland’s elegant and inspiring music also pressed an important message home for all of us to think about in these times: “The promise of growing with faith and with knowing, is born of our sharing our love with our neighbor. The promise of ending in right understanding is peace in our hearts, peace with our neighbor.”

Franz Liszt’s Les preludes (1845-54), is probably the most famous of his 13 tone poems for orchestra. Several members of the Santa Barbara Symphony have likely performed the work many times over the years in various orchestras throughout southern California. Kabaretti took full advantage of his players’ expertise, and delivered an unusually beautiful, elegantly crafted performance of the war horse that not once lost itself in excess. Balances between sections were deliciously clean and clear to the ear (brass suspensions this listener had never heard before for example). Maestro Kabaretti led an expansive but at the same time tightly controlled performance. Memorable, and that’s saying a lot about the conductor’s rapport with his players.

After intermission, Beethoven’s still amazing, still mystifying, still profoundly moving, and essentially immortal Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 (1822-24). For those who have just emerged from under a rock, the Symphony No. 9 was Beethoven’s last. The structure is four movements but the substance of each of those four is revolutionary, particularly the last movement, where Beethoven utilizes massed choirs, four vocal soloists, a marching band, and storm’s fury to accommodate Friedrich Schiller’s An die Freude (Ode to Joy).

Kabaretti, who has conducted Beethoven’s masterpiece on several occasions in various venues worldwide, made it clear by his relaxed but confident manner, he and his incredible orchestra were in familiar, even intimate territory. The first three movements, all instrumental, were a wonder of refinement and taste. Power when needed was rounded and beautiful, the quiet moments, as in the third movement Adagio molto e cantabile, convinced this listener Kabaretti had homeland on his mind; a supremely moving performance by all.

What hasn’t been said a thousand times about the last movement? Here’s a new truth. It’s beginning to be clear, as misunderstandings and copying mishaps of the past two hundred years are clarified and sorted out, Beethoven’s tempos were exactly what he said they were to be – fast. He even notated these fast tempos in the score using the newly invented metronome. Nobody believed him. It will take a long while to spread the word about the exhilaration of performing the last movement at Beethoven’s tempos. Here in Santa Barbara last weekend, conductor Nir Kabaretti was ahead of the pack. Fast!

The result, as choristers, orchestra, soloists, and audience alike discovered, was a whirlwind of energy as Beethoven wanted it; thrilling, fast-paced, full of surprises. The combined choirs sang with new intensity, wonderful balance, and inspiring exaltation – all brightness and fast-paced, exactly as Beethoven wanted it. Ditto the four soloists, whose narratives in ensemble and solo made for conversational not lugubrious vocal exchanges, a pleasure to enjoy on account of Kabaretti’s faster tempos.

Tenor John Matthew Myers dug in with Kabaretti and pushed the tempos of his narrative with vigor. The emotional result was breathtaking, his voice solid. Balance between the four soloists in the famous and brutal solo quartet passages found bass-baritone Cedric Berry in particularly rich low voice. Mezzo Christina Pezzarossi Ramsey made a marvel for the ears of her mid-range color and intelligent articulative maneuvers, accommodating Beethoven’s inner lines with clarity and style. Soprano Johanna Will navigated the notorious heights of her part with considerable clarity, her highest range holding well. It has to be easier to get through all those high C’s, at a faster tempo.

The Santa Barbara Symphony must have relished Kabaretti’s more correct tempos, particularly for the German marching band tune in the Alla Marcia section. As to the audience reaction to Kabaretti’s exciting helmsmanship? No kidding, the last movement held us all in a trance of excitement. During brief musical silences not a sound in the hall. Beethoven’s Choral Symphony always earns standing ovations wherever it’s performed. Audiences last weekend have probably heard and given standing ovations to many previous performances over the years. It’s that kind of masterpiece. But there was something different in the air at last weekend’s performances. Audience, choristers, soloists, musicians knew they had just performed the Ode to Joy as Beethoven intended – at last. Very exciting!

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the review

Larissa FastHorse's The Thanksgiving Play at Ensemble Theatre on October 7, 2023

Read my review for VOICE magazine

Visit Santa Barbara’s Ensemble Theatre Company

Visit Larissa FastHorse’s website

The Thanksgiving Play: Larissa FastHorse’s hilarious black comedy

Celebrating the art of storytelling with one of the most brilliant new plays of the last ten years, Ensemble Theatre Company opened its 45th Santa Barbara season last Saturday at the New Vic with playwright Larissa FastHorse’s The Thanksgiving Play, a drop dead funny (tasteless pun intended), mercilessly eviscerating examination of white America’s “attempt to reconcile the weight of historical inaccuracies with the desire for inclusion and sensitivity,” as the award-winning director for this production, Brian McDonald remarks in his program note.

Highlighting with slashing stilettos of mirth, the tragicomic absurdity in recent years of well-intentioned but naïve attempts by white Americans to make up for what playwright FastHorse (Sicangu Lakota Nation) calls “the longest black comedy in the world,” her funny as an acid bath 2015 masterpiece, which received its Broadway debut in 2023, doesn’t need to mention the near total extermination by the US government of Native Americans over the past couple hundred years to make it’s point; silly platitudes and twisted word salads do not adequately compensate for countless trails of tears, and Wounded Knees. FastHorse, a 2020-2025 MacArthur Fellow, makes it punishingly clear that indigenous peoples understand cycles – there’s nothing new in the white man’s talk, it just goes round and round.

Four superlative professionals, all masterfully intuitive in understanding the substance or lack thereof of their characters, were also acutely attuned to each other on stage at last Saturday’s opening of The Thanksgiving Play. The split-second timing required for successful comedic interaction between the four sparkled with energy. FastHorse’s 90-minute dark comedy danced with wry spirit and agile consequence. Numberless nuanced subtexts and gossamer allusions to Native American terrors past, present, and future sped by, greased with slick, laughter-wracked schtick and timing. Director McDonald did not miss a single opportunity for swift verbal punch or sub-textual superlatives. This cast was surely a dream come true of ensemble creativity and interaction.

The four characters are all white, one of several FastHorse cannonades about who tells history’s tale - the victors. Los Angeles-based Devin Sidel played the earnest if for all the wrong reasons Logan, director in charge of creating a new, politically correct version of the traditional and traditionally wrong First Thanksgiving story. Sidell’s hyperventilated unctuous cloying, her supplications to colleagues about collaboration and community, her rituals of desperate “method,” and her borderline hysterical, usually simultaneous episodes of inspirational hypertension and exhausted fetal retreat made for priceless dollops of comedic opportunity and character caricature. Sidell was on top of every swift-moving gaff and verbal pitfall at last Saturday’s opening – her character fragile intellectually, and shallow in leadership skills.

Aging surfer and occasional theatrical hire, the “cool” character of Jaxton was given perfect Hollywood casting couch insouciance by Los Angeles-based Adam Hagenbuch, no stranger to the endless audition game himself. Jaxton becomes, in Hagenbuch’s crafting of the character, the most rational member of this somewhat squirrely foursome. Jaxton is at least certain of his own certainty, while the others grasp at intellectual and emotional straws. A wonderfully subtle, warmly comedic, and vibrantly human character study by Hagenbuch in his Ensemble Theatre Company debut.

The role of schoolteacher and wannabe playwright Caden is juicy, and southern California-based Will Block escalated his character’s increasingly manic behavior by slow degrees, on a spit of comedic edginess. Quite perfectly over the top from time to time, no easy task, Caden’s character is in a way the most genuine manifestation of emotional truth of the four principals. Walking a tightrope between antipodes of excessive flourish and solid history, Block gave Caden an aura of real if fractious humanity.

Los Angeles-based but more importantly, daughter of the Jersey shore Ashley Platz, turned the dangerous role of sexy but dumb Alicia into a triumph of understated comedic chutzpah. The slightest flaw in empathic understanding of her character, the briefest failure at cha-ching gotcha statement and response synchronicity, a faltering in any way of Alicia’s disarming charms and hilarious mind to mouth faux pas could easily have plunged the character into the dross of stereotype. Platz’ understated exultation of Alicia was, put simply, brilliant.

A single but somehow engrossing set piece by scenic and lighting designer Mike Billings - an elementary school classroom where the four hapless colleagues gather to improvise their way toward collective Thanksgiving consciousness - worked like a charm; chairs and a settee being the means, by which scene variety could be actualized visually. Costume designer Abra Flores dressed her four charges in contemporary So-Cal rehearsal garb, adding a little snigger perhaps, with the character Logan’s ensemble of implied if nerdy authority. Separating scene breaks with devilish funny videos of kids in Pilgrim couture singing blasphemous, ill-fitting Turkey Day lyrics to Christmas favorites was the clever work of Randall Robert Tico, his 17th original music and sound design project for Ensemble Theatre.

Above all, director Brian McDonald deserves kudos with laurels, for a tight, brilliantly staged, diction-perfect – I understood every word – clockwork of precisely timed comedic virtuosity. His spectacular ensemble cast presented a masterpiece in masterful manner.

There’s more though, and it’s what makes FastHorse one of America’s most important playwrights. The number and urgency of issues addressed with wit and forgiving irony in The Thanksgiving Play nevertheless culminate in a fascinating, Godot-like enigma at the very end of the play. Maybe the journey isn’t about becoming anything, but rather about unbecoming everything, so human beings can be what they were meant to be in the first place.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the review

Opera Santa Barbara's 2023-24 season opener: Bizet's Carmen on Friday, September 29, 2023

Visit Opera Santa Barbara

Read my review for VOICE magazine

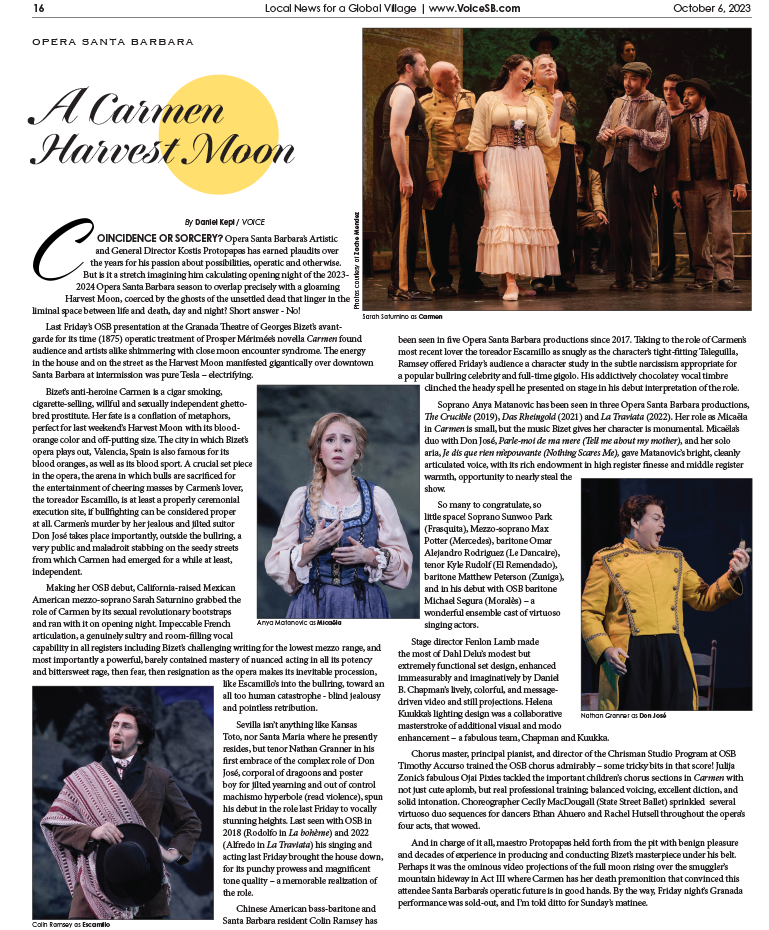

A Carmen Harvest Moon

Coincidence or sorcery? Opera Santa Barbara’s Artistic and General Director Kostis Protopapas has earned plaudits over the years for his passion about possibilities, operatic and otherwise. But is it a stretch imagining him calculating opening night of the 2023-2024 Opera Santa Barbara season to overlap precisely with a gloaming Harvest Moon, coerced by the ghosts of the unsettled dead that linger in the liminal space between life and death, day and night? Short answer - No!

Last Friday’s OSB presentation at the Granada Theatre of Georges Bizet’s avant-garde for its time (1875) operatic treatment of Prosper Mérimée’s novella Carmen found audience and artists alike shimmering with close moon encounter syndrome. The energy in the house and on the street as the Harvest Moon manifested gigantically over downtown Santa Barbara at intermission was pure Tesla – electrifying.

Bizet’s anti-heroine Carmen is a cigar smoking, cigarette-selling, willful and sexually independent ghetto-bred Gypsy prostitute. Her fate is a conflation of metaphors, perfect for last weekend’s Harvest Moon with its blood-orange color and off-putting size. The city in which Bizet’s opera plays out, Sevilla, Spain is also famous for its blood oranges, as well as its blood sport.

A crucial set piece in the opera, the arena in which bulls are sacrificed for the entertainment of cheering masses by Carmen’s lover, the toreador Escamillo, is at least a properly ceremonial execution site, if bullfighting can be considered proper at all. Carmen’s murder by her jealous and jilted suitor Don José takes place importantly, outside the bullring, a very public and maladroit stabbing on the seedy streets from which Carmen had emerged for a while at least, independent.

Making her OSB debut, California-raised Mexican American mezzo-soprano Sarah Saturnino grabbed the role of Carmen by its sexual revolutionary bootstraps and ran with it on opening night. Impeccable French articulation, a genuinely sultry and room-filling vocal capability in all registers including Bizet’s challenging writing for the lowest mezzo range, and most importantly a powerful, barely contained mastery of nuanced acting in all its potency and bittersweet rage, then fear, then resignation as the opera makes its inevitable procession, like Escamillo’s into the bullring, toward an all too human catastrophe - blind jealousy and pointless retribution.

Sevilla isn’t anything like Kansas Toto, nor Santa Maria where he presently resides, but tenor Nathan Granner in his first embrace of the complex role of Don José, corporal of dragoons and poster boy for jilted yearning and out of control machismo hyperbole (read violence), spun his debut in the role last Friday to vocally stunning heights. Last seen with OSB in 2018 (Rodolfo in La bohème) and 2022 (Alfredo in La Traviata) his singing and acting last Friday brought the house down for its punchy prowess and magnificent tone quality – a memorable realization of the role.

Chinese American bass-baritone and Santa Barbara resident Colin Ramsey has been seen in five Opera Santa Barbara productions since 2017. Taking to the role of Carmen’s most recent lover the toreador Escamillo as snugly as the character’s tight-fitting Taleguilla, Ramsey offered Friday’s audience a character study in the subtle narcissism appropriate for a popular bullring celebrity and full-time gigolo. His addictive chocolatey vocal timbre clinched the heady spell he presented on stage in his debut interpretation of the role.

Soprano Anya Matanovic has been seen in three Opera Santa Barbara productions, The Crucible (2019), Das Rheingold (2021) and La Traviata (2022). Her role as Micaëla in Carmen is small, but the music Bizet gives her character is monumental. Micaëla’s duo with Don José, Parle-moi de ma mere (Tell me about my mother), and her solo aria, Je dis que rien m’epouvante (Nothing Scares Me), gave Matanovic’s bright, cleanly articulated voice, with its rich endowment in high register finesse and middle register warmth, opportunity to nearly steal the show.

So many to congratulate, so Little space! Soprano Sunwoo Park (Frasquita), Mezzo-soprano Max Potter (Mercedes), baritone Omar Alejandro Rodriguez (Le Dancaire), tenor Kyle Rudolf (El Remendado), baritone Matthew Peterson (Zuniga), and in his debut with OSB, baritone Michael Segura (Moralès) – a wonderful ensemble cast of virtuoso singing actors.

Stage director Fenlon Lamb made the most of Dahl Delu’s modest but extremely functional set design, enhanced immeasurably and imaginatively by Daniel B. Chapman’s lively, colorful, and message-driven video and still projections. Helena Kuukka’s lighting design was a collaborative masterstroke of additional visual enhancement – a fabulous team, Chapman and Kuukka.

Chorus master, principal pianist, and director of the Chrisman Studio Program at OSB Timothy Accurso trained the OSB chorus admirably – some tricky bits in that score! Julija Zonic’s fabulous Ojai Pixies tackled the important children’s chorus sections in Carmen with not just cute aplomb, but real professional training; balanced voicing, excellent diction, and solid intonation. Choreographer Cecily MacDougall (State Street Ballet) sprinkled several virtuoso duo sequences for dancers Ethan Ahuero and Rachel Hutsell throughout the opera’s four acts, that wowed.

In charge of it all, maestro Protopapas held forth from the pit with benign pleasure and decades of experience producing and conducting Bizet’s masterpiece under his belt. Perhaps it was the ominous video projections of the full moon rising over the smuggler’s mountain hideaway in Act III where Carmen has her death premonition, that convinced this attendee Santa Barbara’s operatic future is in good hands. By the way, Friday night’s Granada performance was sold-out, and I’m told ditto for Sunday’s matinee.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the review

Music Academy Festival Orchestra concert on August 5, 2023 with Hannu Lintu

Read my review for VOICE magazine

Visit conductor Hannu Lintu’s website

Finnish Conductor Hannu Lintu: Painting Big Pictures

Bringing to vivid life, through a tsunami of orchestral color and valorous sound pageantry, two of the most explicitly narrative tone poems of the Romantic era, Richard Strauss’ monumental 55 minute long through-composed masterpiece, Ein Heldenleben: A Hero’s Life, Op. 40 (1898) and Tchaikovsky’s eponymous tribute to eternal love, the Overture-Fantasia Romeo and Juliet (1880), the Music Academy Festival Orchestra wrapped their 2023 summer season last Saturday at the Granada Theatre.

Tall, lean, long armed, and possibly endowed with extra digits on each of his ten fingers, Finnish conductor Hannu Lintu, Chief Conductor of Finnish National Opera and Ballet, wrapped his mind, body, and expressive arms around the task of painting these two graphic musical narratives in a manner that might illuminate and inspire. He succeeded handsomely.

Strauss calls for an enormous orchestra for Ein Heldenleben which opened Saturday’s concert. Several Music Academy faculty members joined the orchestra Fellows to help achieve the composer’s sonic demands. Nine horns, two harps, and two E-flat trumpets boosted the already huge string, wind, brass, and percussion sections of the orchestra to manifest a glimpse into the composer’s massive vision; nothing less than an expression through music, of the pan-Germanic ideal taking shape in the last part of the nineteenth century that ultimately became the modern German state.

Though performed without pause, Ein Heldenleben does segue through several episodic changes in temperament and mood. Strauss later withdrew reference to specific section titles after audiences began to think the work might be about his own life story, filled as Ein Heldenleben is with musical motifs from Strauss’ other tone poems – Also sprach Zarathustra, Till Eulenspiegel, Don Quixote, Don Juan, and Death and Transfiguration.

The hero motif is intoned at the beginning of the piece, the hero’s adversaries are musically diagrammed next, and the obligatory love companion is exquisitely developed musically in the third sequence of the tone poem. Battle scenes and works of peace that follow victory serve as denouement to the hero’s ultimate retirement from this world and completion of life’s journey.

No stranger to the art of illuminating all manner of complex visual/musical scenes in his role as Chief Conductor at Finnish National Opera, Lintu danced and prowled the tiny confines of the Granada’s podium, leaning precariously this way, then that as he addressed various matters of balance, color, and subtext in Strauss’ magnum opus. During the battle sequence, which contains some of the most powerful brass ensemble writing in the repertoire, Lintu flung his arms in cyclonic fits on more than one occasion to describe the imaginary scene. The Festival Orchestra responded appropriately, caught in the conductor’s overwhelming energy vortex.

Making nearly tangible his long-armed embrace of the entire orchestra during spacious arcs of lush string sound or broad woodwind passages, Lintu inhaled his colleagues’ enthusiasm to please, and exhaled with every sinew of his lithe physique and expressive intellect wave after wave of simply gorgeous music making. The hour-long Ein Heldenleben narrative flew by. That’s synergy.

After a needed intermission to gossip about the epic Strauss tone poem just heard, Lintu and the Festival Orchestra gave us exactly what we needed to wind down the evening, Tchaikovsky’s bittersweet yet somehow hopeful tone poem Romeo and Juliet, in a performance that shimmered with well-prepared sectional balances, featured carefully tapered and extended phrasing, and focused the confrontational sequences between rival Montague and Capulet clans on the musical virtues of clean articulation and controlled dynamic. A first-rate performance.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Music Academy Festival Orchestra concert on July 29, 2023 with conductor JoAnn Falletta

Enjoy reading my review for VOICE magazine

Visit JoAnn Falletta’s website

JoAnn Falletta: Surprises & Satisfactions

American conductor JoAnn Falletta is one of those extraordinary forces of art and nature who tears the fabric of convention to shreds but always tidies up the scene of each of her several apotheoses. Importantly, she never looks back.

The litany of orchestras Falletta has helmed and recordings she’s made is legion. Watching her conduct last Saturday’s Music Academy Festival Orchestra concert at the Granada Theatre in Santa Barbara, a concoction of spicy magical realism (Roberto Sierra’s Fandangos), French angst (Maurice Ravel’s La Valse), and Russian mystery (Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances, Op. 45), it became clear immediately, Falletta was not just in charge but in supreme command of every color-filled, rhythm-bursting moment of Fandangos and later, the Ravel (a revelatory performance), and moody Rachmaninoff.

Walking onto the Granada stage looking for all the world like a worried mom fussing over her massive family of musicians, Falletta’s conducting – straight and clean and clear, but not particularly charismatic – did not in the first nanoseconds of the evening appear to be lighting any fires. Then the high brass fanfares began in the opening moments of the Sierra piece – unique sparkles of thrillingly complicated color.

Falletta, still no-nonsense about stick technique, nevertheless began a slow melt into a subtler and palpably effective body language of rhythm and pulse that successfully lured her colleagues into a slow-dance crescendo of such excited intensity the piece reached full rollicking throttle while the audience held its breath; a spectacular take by Roberto Sierra on two earlier fandangos by predecessors Soler and Boccherini. The orchestra, now thoroughly seasoned as an ensemble for this, its next to last concert of the summer season, gave Fandangos a slick performance, and Falletta 120% of their attention.

Before conducting Maurice Ravel’s La valse (1919-1920), JoAnn Falletta took a few minutes to instruct the audience about the piece. Both La valse and his other masterpiece Boléro (1928) hold profound messages in their harmonic and structural incongruities. Ravel, a survivor barely, of World War I, was injured physically and psychologically by the experience. La Valse, like Boléro, eventually collapses of its own weight and hysteria; the waltz pattern in La valse is a musical totem to antebellum Europe, washed away in a confused tidal wave of blood and despair.

The opening bars, conducted by Falletta as a throbbing heartbeat, were just the first of several interpretive revelations brought to the listener’s attention. Little pockets of color not noticed before came into audible play under Falletta’s microscopic attentions. And with unerring noblesse oblige, Falletta advocated on behalf of Ravel’s sense of outrage about the effects of world conflict on societies. Finesse and elasticity of bar line, orchestral sighs and pouts, ominous forebodings from the bottom of the orchestra that build to its hysterical climax – made for a particularly thoughtful and inspired interpretation of La valse.

Sergei Rachmaninoff’s last major composition, the Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (1940), were created during the composer’s only stay in the United States at Centerport, New York, overlooking Long Island Sound. Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered the work in January 1941, as another world war began to ravage the European continent, including the composer’s homeland.

Falletta and the Festival Orchestra plumbed the richly Russo-nostalgic three dances of the suite with particular emphasis on Rachmaninoff’s gorgeous orchestrations, including his lush string writing, which Falletta dug into with unabashed gusto. Balances throughout and between various sections of the orchestra were carefully tweaked by the conductor for maximum color.

If heartbreak were an instrument, Rachmaninoff’s use of alto sax, his breathtaking melodies for high strings, his orchestral whispers and sighs describe the composer’s homesickness for Russia with unadulterated, post-revolution passion. Falletta, whose powers of persuasion are those of a goddess – gentle, and without error – gave her Festival Orchestra colleagues several lessons in the art of interpretation, and her audience several opportunities to cheer.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the review

Music Academy Festival Orchestra & Chorus concert on July 1, 2023

Read my review for VOICE magazine

Visit the Music Academy

Visit conductor Osmo Vänskä’s website

Visit American composer Jessie Montgomery’s website

Conductor Osmo Vänskä - From Here to Eternity

A Nicola Tesla of the podium, conducting energy instead of notes, allowing musical phrases to soar by not controlling them, Grammy winning Finnish conductor Osmo Vänskä led the Music Academy Festival Orchestra and Festival Chorus in an eclectic program last Saturday night at the Granada Theatre that also electrified for its successful destruction of the bar line. Sometimes hard to follow, Vänskä’s gestures and cues were more about endorphins than textbook technique. The conductor successfully convinced his colleagues in the orchestra to trust intuition and impulse, his and theirs, go out on more than a few musical limbs with him, and by taking such risks discover the magic and freedom of unbridled expression.

Music by Leonard Bernstein, the Overture to his 1956 operetta Candide; American composer Jessie Montgomery, the West Coast premiere of her Hymn for Everyone, which enjoyed its first performance by the Chicago Symphony this past April; and Gustav Holst’s enduring masterpiece from 1914-1917, The Planets, Op. 32, found Vänskä’s presence on stage – a roiling Delphic oracle – inspired and purposeful.

Conductor Laureate of the Minnesota Orchestra and now guest conductor to the world, Vänskä’s is a technique that while often nearly incomprehensible to the eye, achieves stunning artistic result. This follower of Music Academy concerts since the early 1960s was reminded of the legendary conducting machinations of Maurice Abravanel. Vänskä like Abravanel, is all over the place between bar lines, often crashing into guardrails of structural order in the name of elastic phrasing. But when push comes to shove - those moments when an orchestra needs a traffic cop to keep it all together - Vänskä is crystal clear in his movement and focus, as was Abravanel.

From the opening fanfare of the Overture to Candide it was clear something different, even revelatory was afoot in Vänskä’s interpretation of this popular concert opener. Fluid, textured, easy going in its various raptures and feints, the maestro’s coaxing and shaping of the musical narrative was a symphony of intuitive movement liberated from strict stick technique. The orchestra in turn plunged into the deep end of nuance with their chief, and together they gave the full house at the Granada Theatre a truly rapturous and joyful performance.

American composer Jessie Montgomery is finishing her third and final year as the Mead Composer-in-Residence of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Her Hymn for Everyone, premiered by the Chicago Symphony in April 2023 and receiving its West Coast premiere last Saturday, is the last of three commissions during her residency. A meditation on memory and loss, Hymn for Everyone is in the composer’s own words, “a bit of a catharsis,” created during the isolation of COVID and speaking to its aftershocks, while also reflecting on the death of Montgomery’s mother in 2021.

Conducting this new work with precise due-diligence, Vänskä embraced and nurtured the low unison dirge that opens and sets the mood for all that follows. Montgomery’s orchestrations invoke ecstasy as easily as atonement, particularly a few minutes into the piece, when the dark opening dirge becomes briefly ecstatic – fabulous messaging. Montgomery’s subtle color constructs, including some fascinating unison instrumental pairings like high strings and tuba, revealed a keen understanding of musical color as psychological epiphany. Hymn for Everyone reaches a final breaking point – relentless dirge rhythms from a massive percussion battery, then softens to a clarinet meditation with other solo winds and strings, and softly out.

Gustav Holst (1874-1934) began work on his seven-movement exploration of the inner and outer planets of our Solar System, The Planets, Op. 32, in 1914 and somehow managed to complete the suite by 1917 while World War One raged around him. It should be no surprise The Planets is far more than its astronomical nomenclature. Maestro Vänskä became, not to take this metaphor much further, a Tesla Coil of conducting energy and leadership from the first ominous drumbeats of Mars, straight through the gloriously achieved sirens (thanks, William Long, Festival Chorus chorusmaster) of the final movement, Neptune.

Highlights: sonic thrills as only the Music Academy Festival Orchestra can muster, in an edge-of-seat performance of Mars, Vänskä winding up the tension and drama of “the Bringer of War” to near hysterical levels. We all loved it. A shimmering performance of the surreal second movement, Venus, the Bringer of Peace; a superbly conducted and masterfully executed performance of the lively third movement, Mercury, the Winged Messenger; a lovingly conducted fourth movement, Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity with its always moving anthem, now Britain’s national hymn, I Vow to Thee, My Country.

The stunning power of Vänskä’s body movements, oozing rhythm and energy even in stasis during Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age; the fabulous musical storytelling of Uranus, the Magician; and as mentioned earlier, the mystical allure of eternity as beautifully realized by the backstage chorus in Neptune, the Mystic.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Osmo Vänskä conducting the Music Academy Festival Orchestra on July 1, 2023 at Santa Barbara's Granada Theatre - photos by Zach Mendez

Download a PDF of the review

American composer Jessie Montgomery receives applause after the West Coast Premiere of her new work, Hymn for Everyone

Music Academy Festival Orchestra on June 24, 2023: all Berlioz concert

Read my review for VOICE magazine

Visit the Music Academy

Visit conductor Stéphane Denève’s website

Visit mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke’s website

All Berlioz program - Beauty and the Beast!

Alchemy, witches cauldrons, death by execution, summer nights both sanguine and otherwise; a Julia Childs masterpiece of sweet and savory sounds stirred up last Saturday’s Academy Festival Orchestra program at the Granada Theatre. Featuring the Music Academy’s Lehrer Vocal Institute co-chair, mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke, in a radiant performance of the composer’s 1841 song cycle Les Nuits d’été (Summer Nights) Op. 7 and concluding – how could it have been otherwise? - with Berlioz’ 1830 hallucinogenic opium trip, Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14, the concert left the audience spellbound and punch drunk. A glorious night!