Los Angeles Philharmonic-100th anniversary concert in Santa Barbara — read the review

Visit the Los Angeles Philharmonic website

Visit conductor Gustavo Dudamel’s website

Visit the Community Arts Music Association website

++ Here is my review for Santa Barbara’s arts weekly VOICE Magazine of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s 100th anniversary concert in Santa Barbara on March 6 2020:

LA Philharmonic, Ives and Dvorák — Three American Masterpieces

Santa Barbara’s Community Arts Music Association celebrated 100 years hosting concerts here by the world’s great orchestras on March 6 with a day of centennial events, followed by an historic Los Angeles Philharmonic concert at the Granada Theatre and an after party at nearby Santa Barbara Museum of Art that blew the lid off the city’s social calendar and reminded the thoughtful how lucky is this tiny metropolis for its vigorous and long-lived cultural good health.

March 6 marked the 100th anniversary of CAMA’s first concert presentation, the debut performance in Santa Barbara by the then one-year old Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Potter Hotel Theater in 1920. The orchestra’s history of regular performances in Santa Barbara continued after the demise by fire of the Potter Hotel in 1922 with regular CAMA bookings at the new (1925) Granada Theatre beginning during the 1925-26 season. Miraculously, the nine-story Granada building survived the 1925 earthquake and is the city’s first, last and only skyscraper. CAMA has sponsored orchestras from around the world in the now fully refurbished venue more or less regularly since 1925.

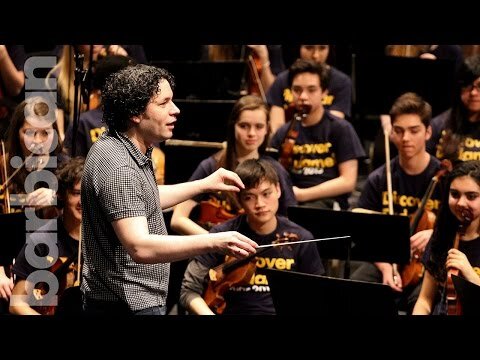

Last Friday’s LA Phil program, led by Music and Artistic Director Gustavo Dudamel, consisted of two monumental masterpieces, each inspired by the American experience. American composer Charles Ives’ Symphony No. 2 (1897-1909) opened the program and Czech composer Antonín Dvorák’s Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, Op. 95 - From the New World (1893) which was performed at the first LA Phil concert here in 1920, concluded the concert and brought a sold-out for months, Granada Theatre audience to its feet in a gush of community and artistic pride.

The third American masterpiece of the evening was the Los Angeles Philharmonic itself; a glorious living artistic organism and model for the consanguinity of the human experience, artistic integrity and creative empathy: e pluribus unum. Led by one of the great conducting geniuses of this century, the orchestra is a composite of world experience, but also a willing expressive conduit for Dudamel’s interpretive inspirations. A violist in the orchestra told me after the concert and with pride of profession that when Gustavo is on the podium, there is no room, no time for anything other than total commitment to his scholarship and interpretive vision.

Dudamel’s exacting command of orchestral color, dynamic terracing, mood, pulse, balance and voicing detail was palpable from the opening bars of Charles Ives’ masterpiece of American magic realism, his soul defining Symphony No. 2. It’s 40 minutes and several tableaux of a more rural America from Ives’ youthful memory, long lost even by the turn of the last century, flew by with cinematic intensity as the composer’s vivid musical portraits and frequent quotes from folk songs, patriotic tunes, spirituals and even little snippets of Dvorák/Brahms passed before our ears and imaginations with intuitive thus hypnotic, clarity. Eschewing stereotypes about how to interpret the piece, Dudamel and the orchestra turned in an Ives Second that was refreshingly romantic in pace and elegance, while also loaded with fresh ideas and asides.

Too easily dismissed as flip since its premiere in 1957 some years after the composer’s death, Dudamel’s approach to the Second Symphony was instead reverent and thoughtful. The result, a revelatory manifesto from the composer, discovered and delivered with clarity by conductor Dudamel that spoke volumes about Ives the man, the genius, the visionary and revisionist. Regarding the last and most notorious chord (discord) of Ives’ Symphony No. 2? Perfectly horrible, delivered with perfectly tuned and forceful irony.

After intermission and with thrilling intention and purpose, Antonín Dvorák’s Symphony No. 9 – From the New World. Conducting from memory, Dudamel proceeded without wink or nod to re-imagine this iconic and touching homage to the American id with heady dollops of personal as well as artistic insight informing every distinctively nuanced thread of his interpretation. Foreigners often know us better than we know ourselves and Dvorák’s take on Americans from the 1890’s conflated with Dudamel’s impressions of norteamericanos from his own experience, made for a remarkably pertinent and profoundly moving musical and intellectual experience. The packed house exploded, but not before 10 or more seconds of utter silence after the last, strangely bittersweet diminuendo chord of the work had long since ceased to exist sonically, but hovered still in consciousness. Dudamel finally dropped his hands - one of those goose bump moments that will be remembered for a generation by those in attendance – and an insanity of rapturous applause, shouts and whistles brought Dudamel back to the stage several times before everybody went home.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Gustavo Dudamel talks about working with the Berliner Philharmoniker

Vienna Philharmonic - Dvořák: Symphony No. 9 'From the New World', IV. Allegro con fuoco

Gustavo Dudamel's musical mission

Discover Dudamel