Santa Barbara Symphony program notes May 13-14 2023: Platinum Sounds

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit violinist Philippe Quint’s website

Visit composer Jonathan Leshnoff’s website

Read my review of the May 14 2023 performance

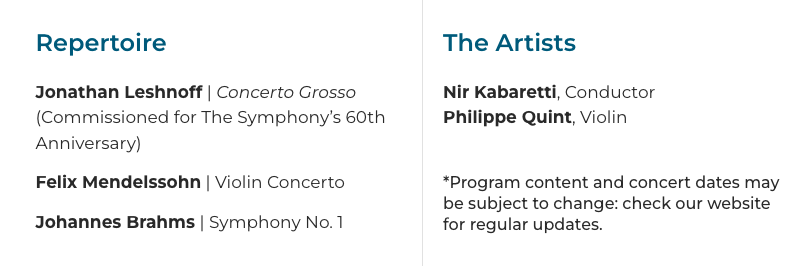

Platinum Sounds: The Symphony Turns 70

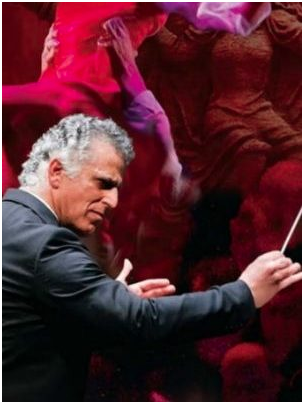

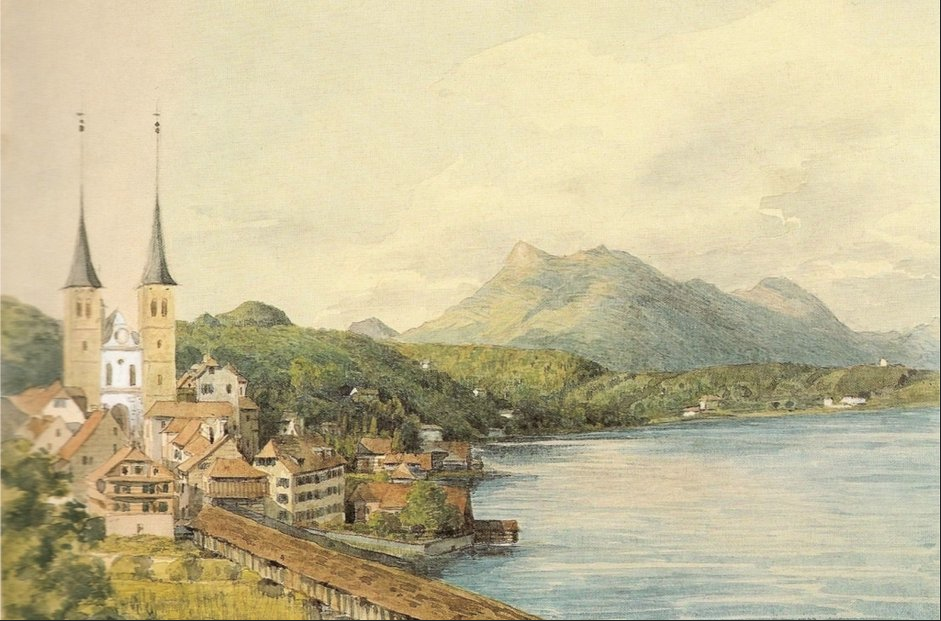

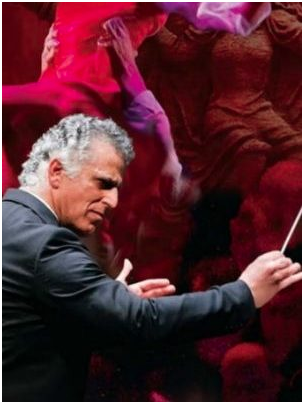

The May 13-14 2023 concerts celebrate the orchestra’s 70th anniversary season with a particularly thoughtful program. Conductor Nir Kabaretti looks at juxtapositions; past, present, and future. Opening with a work commissioned by the orchestra to mark its 60th birthday, American composer Jonathon Leshnoff’s Concerto Grosso (2012), Kabaretti next turns the spotlight on a guest artist who last appeared with the orchestra in 2017, Russian-born American violinist Phillipe Quint. Felix Mendelssohn’s cheerfully enigmatic Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1838-1844) is the centerpiece for Quint’s return visit. Bringing the concert to a properly platinum close, maestro Kabaretti channels the Classical Period (Mozart, Haydn) through the lush, late romantic polyphony of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 (1855-1876).

Baltimore-based American composer Jonathan Leshnoff (1973-) has become one of the most widely performed composers in the world. Described by the Baltimore Sun as “cohesively constructed and radiantly lyrical,” Leshnoff’s enormous portfolio of symphonies, oratorios, chamber music, and concertos have consistently satisfied concert audiences without compromising compositional integrity for popular accessibility.

After conversations between conductor Nir Kabaretti and the composer, the Santa Barbara Symphony commissioned Leshnoff in 2012 to compose a work that would feature several of the orchestra’s principal players. Concerto Grosso in the Baroque Style, modeled after the Baroque concerto grosso form, was given its premiere in Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre on March 16-17, 2013.

Highlighting ten principal soloists from the orchestra during its four movements, the first movement, Allegro, features two violin soloists in a perfectly crafted 21st century tip of the hat to Vivaldi, Bach et al. The second movement’s simple instruction, quarter note = 60, indicates its dirge-like tempo and temperament, offering solo and chamber ensemble moments to a unique combination of four soloists - cello, trumpet, trombone, and horn - a fascinating timbral cocktail.

The third movement, dotted quarter note = +128, gives florid compositional attention to the principal flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon chairs with various solo and chamber music combinations. Flighty and fun, its pleasant tune flows through the wind soloists and orchestral accompaniment like a rolling wave. The fourth and last movement of Concerto Grosso, Finale, brings all ten soloists together for what the composer described on stage before the premiere in 2013 as a “Stravinsky pep, that just keeps it running through to the end.”

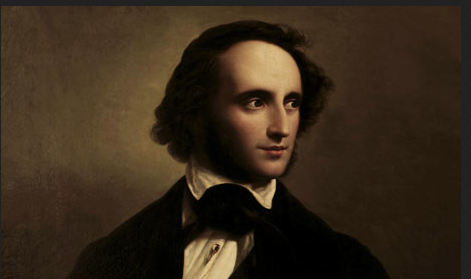

With his appointment as conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1835 composer, pianist, organist, editor, and conductor Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), threw himself into the musical life of the town, founding its music conservatory, editing the prestigious Leipzig music journal, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, conducting at the city’s opera house, and championing the music of Schubert and Schumann. Little wonder he died young there, at the age of 38.

Contemplating composing his first violin concerto after consultations with his Gewandhaus Orchestra concertmaster, Ferdinand David, Mendelssohn initially sketched out in 1838 what would become his Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64, finally premiering the multiply revised final product with the orchestra and David as soloist in 1845 – two years before the composer’s early passing. The Violin Concerto was an instant success with the public and violin virtuosi alike, remaining at the top of the repertoire, to this day.

Bubbling for the most part with Puckish jollity and lightheartedness – a fascinating echo of the energy and optimism of his incidental music three years earlier to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1842), the Violin Concerto, his last composition in the concerto genre, is also reflective and subtly enigmatic. While the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream is in E Major, a jolly key, two years on, Mendelssohn needed E minor as the expressive tonal nimbus for his Violin Concerto; a musical metaphor perhaps, for his increasingly fragile psychological as well as physical health toward the end of his life.

The first movement, Allegro molto appassionato has the soloist playing with the orchestra from the very first bars, an innovation that must have excited audiences at the time, as it still does today. A gorgeous melody, tempered in moody reflection with a touch of ironic sadness, comes and goes between recurrent bursts of cheerful energy. A final, nearly manic cadenza before a last romantic interlude, is followed by a speed fest of virtuoso writing for orchestra and soloist that brings the movement to an exhilarating close.

The slow movement, Andante – Allegro non troppo, is the cipher that discloses a deeper story. A lonely solo bassoon tone is suspended in the silence between first and second movements, a prescient umbilical connection of emotional subtexts, and an eerily and completely unique musical special effect. A gorgeous, somewhat yearning waltz-like tune begins the movement with compelling certainty. Surges of romantic sighs prepare the scene for increasingly passionate ascending sequences from the soloist, answered in-kind by the orchestra. The movement settles finally, into a Peaceable Kingdom of exhausted calm.

The last movement Allegro molto vivace opens with a few lingering dramatic sighs from the earlier movement, before a martial but elegant brass fanfare announces a new quadrille and with it, a return to the lively pace and frolicsome charm inspired by the composer’s early music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The concerto ends in a hail of virtuoso solo fiddling and orchestral brilliance.

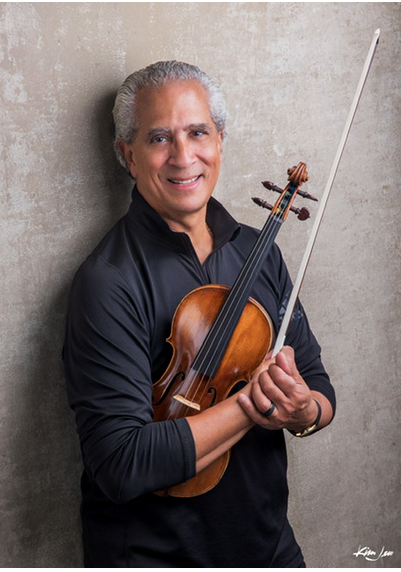

Russian-born violinist Philippe Quint (1974-) studied at the Special Music School for the Gifted in Moscow, making his debut as a concerto soloist at the age of nine. Immigrating to the United States in 1991 to study at The Juilliard School, Quint earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees there. He is now an American citizen. Philippe Quint has appeared with orchestras around the world, including his appearance with the Santa Barbara Symphony in 2017 playing Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, and Astor Piazzolla’s, The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires. The artist plays a 1708 “Ruby” Antonio Stradivari violin, a loan from the Stradivari Society, a philanthropic organization based in Chicago.

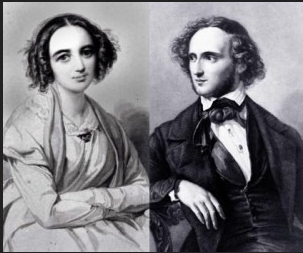

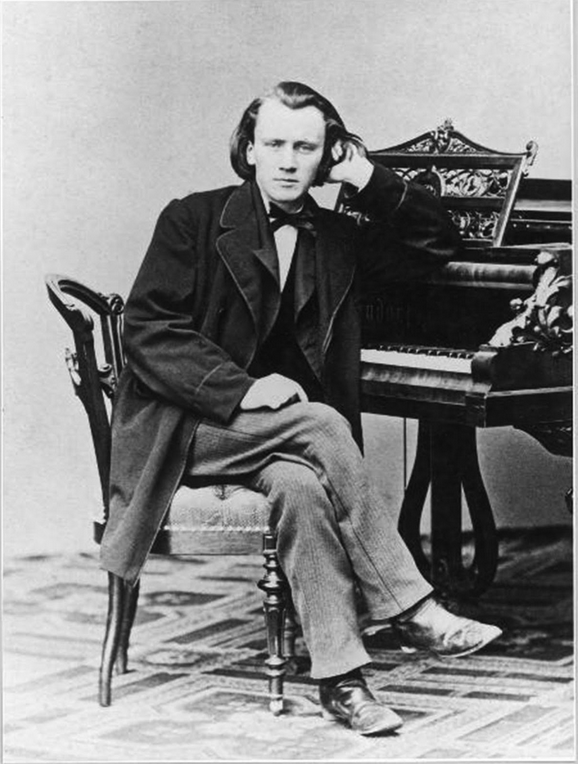

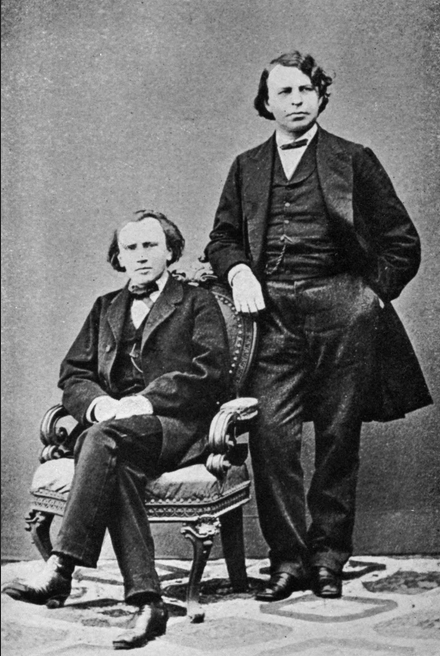

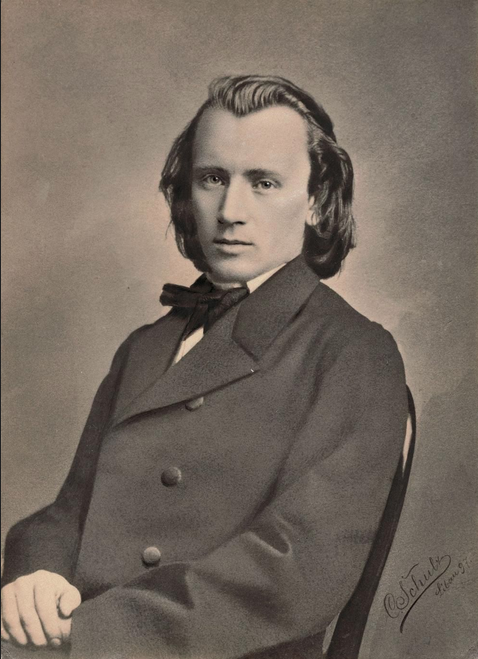

For Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) the 1850’s, when he was in his late teens and early 20’s, were fraught with passion, rejection, and self-doubt. The young genius ran with an impressive crowd, including Felix Mendelssohn, and Clara and Robert Schumann among others. Falling hopelessly in love with Clara, Brahms even moved in with the Schumann family to help with their growing flock of children and Robert’s increasing mental instability; a ruse of course on Brahms’ part, to be closer to the source of his lifelong infatuation. Clara, grateful for the handsome young Brahms’ support, nevertheless was quite clear with him about the impossibility of a more intimate relationship.

Brahms began sketches for his Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 in 1854, just two years before Robert Schumann’s death at age 46 in 1856, and after an earlier attempt at a symphony that morphed into his Piano Concerto No. 1, in D minor, Op. 15 (1858). It took the composer another 22 years of revisions, re-writes, doubt, and hesitancy, before he allowed a first performance of the Symphony No. 1 in 1876.

While Mendelssohn’s seven-year long Violin Concerto project can be comfortably attributed to the composer’s practical desire to create a virtuoso masterpiece for the ages (he succeeded), Brahms’ several re-writes and delays in finishing and finally producing his sometimes troubling and arduous, ultimately triumphant Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68, are more difficult to decode.

Clara Schumann looms large as the secret emotional backstory for this work; a gossamer and reticent presence to be sure yet possessing a powerfully intoxicating intellectual and sexual attraction for the composer. After Schumann’s death, Clara remained a widow for the rest of her life, as the Victorian age dictated. Brahms too, remained single, his passions and disappointments expressed in his music.

With its harsh opening bars and insistently pounding fate rhythm on timpani, the first movement, Un poco sostenuto – Allegro, begins in a state of catastrophic predilection. There are eye-of-the-storm calms in an otherwise anxious first movement, but a building wave of orchestral sighs regenerates the tempest, time and again. Finally, in exhausted resignation, the movement an enormous, nearly stand-alone tone poem on romantic angst, settles like the Titanic at the nadir of its plunge, in dark, uneasy quiet.

Nothing short of a love song, the second movement, Andante sostenuto, is a prayer of longing that builds to an ecstatic, bittersweet-tinged soliloquy of adoration and unrequited love. Near the end of the movement, a horn and fiddle duo of nearly unbearable delicacy like the movement itself, is one of the tenderest accounts of heartbreak in the repertoire.

A leisurely walk in the woods is the opening imagery of the third movement, Un poco allegretto e grazioso, a mood that eventually morphs phoenix-like through several orchestral sighs toward a noble theme of magnificent breadth and optimism, then back to the woodland idyll of the beginning of the movement, this time slightly tinged in subtle apprehension, preparing the listener for the dramatic emotional opening section of the last movement, Adagio – Più andante – Allegro non troppo, ma con brio – Più allegro.

The movement’s long title indicates the sturm und drang of its several moody episodes, but with the introduction of the main theme in strings, Brahms announces a change of psyche, the beginning of an orchestral tsunami of spiritual triumph that reaches its ecstatic peak with the introduction of a stunning brass choir tune that propels the movement to its hair-raising final bars.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the program notes

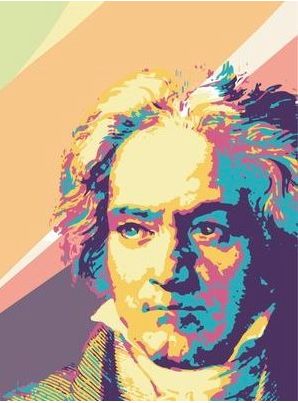

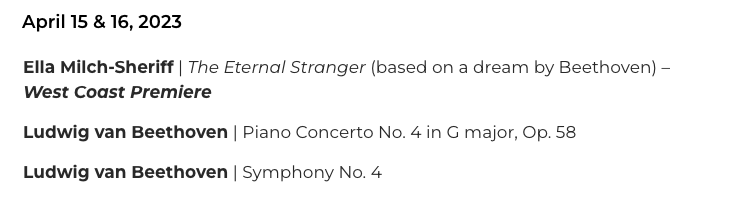

Santa Barbara Symphony program notes April 15-16 2023: Beethoven Dreams

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit composer Ella Milch-Sheriff’s website

Visit Santa Barbara’s Ensemble Theatre Company website

Read my review of the April 15 2023 concert

Beethoven Dreams

Music and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti has constructed a Beethoven-centric program for the April 15 and 16 concert pair that explores the good, the bad, and the truly mystical aspects of Beethoven’s exceptionalism in the world; a loss of hearing that began in 1798 and left him completely deaf by 1818. Shuttered from in-the-moment shared experience with others as his deafness became a social sepulcher, the composer’s inner mind, a consciousness free of the boundaries of time, place, and conventional expectation, flourished.

“In order to create a work of art you need distance,” according to contemporary Israeli composer Ella Milch-Sheriff, whose 2020 Monodrama for Actor and Orchestra: The Eternal Stranger, to a text by Joshua Sobol, opens the concert. In artistic collaboration with Santa Barbara’s Ensemble Theatre Company (ETC), the West Coast Premiere of Milch-Sheriff’s contemporary score at first seems light years from Beethoven’s sound world. Or is it?

The Eternal Stranger is a complex and multi-layered meditation containing aural, theatrical, and symbolic imagery inspired by a letter from 1821 in which Beethoven describes a dream about a long journey over changing geography and cultures. Ensemble Theatre Company’s Artistic Director, Jonathan Fox, directs the two actor narrative. Ella Milch-Sheriff’s ear-opening examination of displacement serves as the thought-provoking catalyst for the entire concert program.

A delicate thread of unusual tonal continuity links present and past; Milch-Sheriff’s mystical Beethovenian journey, and the next two Beethoven works maestro Kabaretti has chosen for this program, both composed during a burst of creative energy in 1805 and 1806. The Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 (1805-1806), with guest artist, pianist Inna Faliks, and the sunny Symphony No. 4 in Bb Major, Op. 60 (1806) express poignantly, Beethoven’s continued optimism in the face of a soul-crushing reality.

By 1821 Beethoven, now totally deaf and communicating with visitors by exchanging written notes, slipped deeper into an inner world of private thought and subconscious creativity. A stranger for the rest of his life except in memory, to the sounds and interactions of the outside world which for him had gone completely silent, he wrote his friend and publisher Tobias Haslinger on September 10, 1821, a letter that remained mostly unknown to biographers until recently.

Beethoven describes a dream about a very long journey “as far even as Syria, as far even as India, as far even as Arabia,” culminating at Jerusalem, where his friend the publisher greets him with an epiphanic but secret revelation. Beethoven includes a hastily sketched musical sequence in contrapuntal canon form, a dream-inspired conscious afterthought Ella Milch-Sheriff references subtly in The Eternal Stranger.

Israeli composer Ella Milch-Sheriff was commissioned by conductor Omer Meir Wellber in 2019 to compose a work commemorating Beethoven’s 250th birthday the following year. Empathizing with the composer’s increasing isolation from society because of deafness, searching for a contemporary text that might express that loneliness, Milch-Sheriff quickly discovered Israeli playwright and author Joshua Sobol’s poem, The Eternal Stranger, inspired by Beethoven’s mysterious dream letter from 1821.

“Whenever I compose for text, I become identified with its content - it becomes me,” Milch-Sheriff writes. “This work is about a stranger, a refugee, or any other person in a hostile environment with no legitimate reason to be rejected but the fact that they are different, look different, move differently, speak differently.” Milch-Sheriff continues. “The Beethoven dream letter and Joshua Sobol’s poem enabled me to use vast musical connotations from my home country of Israel and the sounds of my childhood; a mixture of Arabic music, Jewish music of all kinds (eastern and western) as well as the music of the old European world.”

With an Ensemble Theatre Company actor in silent, motionless repose on stage (Beethoven dreaming?) The Eternal Stranger begins in a mist of atavistic sonic mystery; low string and wind rumble under high string harmonics create a mood of spooky divination. As the score becomes more colorful, with oboe and bassoon narratives and denser wind/brass textures, the sleeper awakens and begins to move about the stage, reciting Joshua Sobol’s first stanza: “On a shore where a wave from the stormy ocean tossed him. Seeking to grasp the ways of the people there, the masters of the land. They take him for a misanthrope. He can see it . . . by the looks in their eyes.”

A waltz-like section, increasingly frenzied, colors the narrator’s response: “I am not a misanthrope! On the contrary! I love people, I also love animals, plants, and the woods; All of nature.” A new section, an ironically fateful and darkly orchestrated march to Sobol’s words, “My mother’s language is buried in me. Her voice in quietude is calling to me,” produces The Eternal Stranger’s musical apotheosis; a flash of emotionally paralyzing high string angst, followed by an uncanny calm, the narrator reacting to the event with his only prop, a hand drum, “Letting the dead people be resurrected in a dream!” Finally, a brief but terrifying orchestral maelstrom, fabulously conceived and magnificently orchestrated by the composer, explodes then dies away to the final words, as also at the beginning of the narrative, “A man is observing people . . .”

Whether in cahoots with the composer, or simply as the result of a novel personal programming notion, conductor Omer Meir Wellber, who commissioned The Eternal Stranger, chose to link without break Milch-Sheriff’s work to Beethoven’s Mass in C Major for a video performance at Teatro Massimo in Palermo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMQVk4ZZtHA – a marvelous artistic maneuver that bonded nineteenth century Beethoven to the twenty-first century, exactly the purpose of composer Ella Milch-Sheriff’s Monodrama. For the West Coast premiere of The Eternal Stranger in Santa Barbara, the last bar segues directly as well, this time to the solo piano passage that opens Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4.

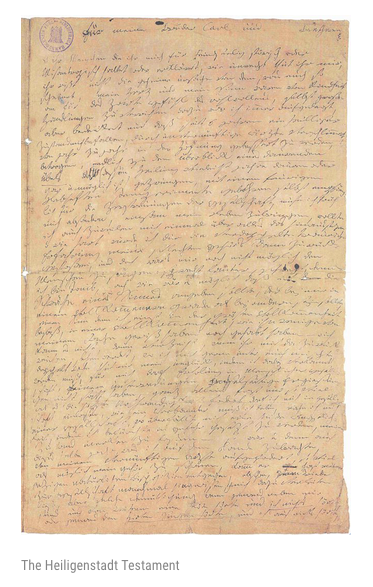

Dated 6 October 1802 and referred to by historians as the Heiligenstadt testament, Beethoven (1770-1827) penned a note to himself he kept secret the rest of his life – a stream of consciousness rant about his agony at being so offhandedly misunderstood because of his hearing loss, which he managed to keep secret for several years. It reads in part: "O you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you.” With dire thoughts about the reality of his increasingly debilitating affliction occupying his horrified mind as early as 1802, it is all the more astonishing Beethoven was able to create several of the most optimistic works of his entire catalogue during that period, especially the two buoyant works on this program, composed in 1805-1806.

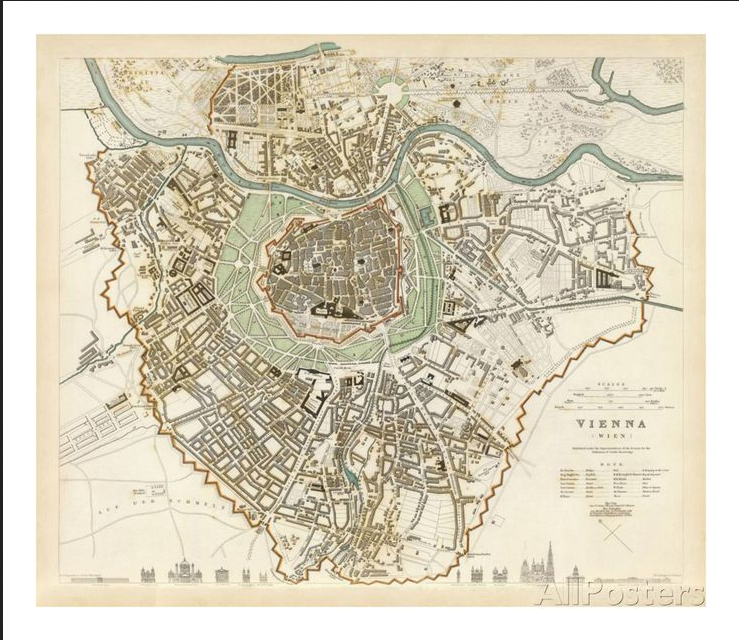

The Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 (1805-1806) was premiered in Vienna in 1808, as the Napoleonic Wars were beginning to tear Europe to pieces. The composer, not yet totally incapacitated by his hearing loss, was able to function as piano soloist for the concerto’s debut. The first movement, Allegro moderato, is unique and visionary, from its quiet opening solo piano statement, echoed softly by the orchestra, to the extended orchestral section immediately after, the pianist remaining still during that section before the two protagonists engage each other in narrative, their various virtuoso musical jousts and cadenzas choreographed carefully by the composer.

The second movement, Andante con moto, with its forceful, even sternly judgmental opening orchestral sequences, the piano a meek supplicant in response to each, eventually yields to the piano’s more eloquent plea for calm and reason. The admonition motive diminishing, emotions ebb and flow. Reveries and sighs, both orchestral and in solo piano, suggest struggle and denial. The movement reaches exhausted resignation, then segues Guignol-like, into an off-the-string orchestral gallop that erases all previous doubt, and presents the third movement, Rondo vivace, at a jolly pace. Bravura exchanges between soloist and orchestra embellish the thematic material cleverly, Beethoven squeezing every drop of developmental possibility from his tunes – a triumph of compositional invention and colorful orchestration.

Ukrainian-born pianist Inna Faliks is Professor and Head of Piano at UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. “Adventurous and passionate” (The New Yorker), she has established herself as one of the most exciting, committed, communicative, and poetic artists of her generation, a champion of the standard repertoire as well as genre-bending interdisciplinary projects by contemporary composers. A writer as well as world-traveling concert pianist, Inna Faliks’ musical memoir, Weight in the Fingertips was published in 2023.

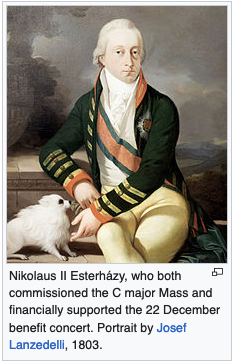

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in Bb Major, Op. 60 (1806) was premiered in Vienna in 1808 on the same four-hour long program as his Piano Concerto No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, and the Choral Fantasy – a gala benefit concert on behalf of the composer.

Mixed reviews greeted the Symphony No. 4. It’s first movement, Adagio – Allegro vivace, clearly an homage in structure at least to the opening sections of Haydn’s late symphonies, its slow introduction inching hesitantly toward a sudden tidal wave of vigorous energy and change of mood, may have seemed a bit old fashioned to the audience. Nevertheless, the Allegro vivace section is one of the most inventive in the symphonic repertoire; bright and youthful, with unpretentious dollops of happiness – a sparkling musical jewel.

The second movement, Adagio, which Hector Berlioz declared to be the work of the Archangel Michael, is a strangely awkward lullaby, its odd and emphatically repetitive dotted rhythmic figure morphing over time and compositional development into a noble hymn - courage in the face of adversity? The last bars settle into the sound imagery of a woodland idyll akin to the ambiance of the Symphony No. 6, Pastorale (1808); a fond memory of the composer’s many happy walks in the German countryside, whose intimate sounds would soon be lost forever to his ears.

If the first stage of grief is denial, the years from Beethoven’s hearing loss diagnosis (1798) to his Vienna benefit concert in 1808 might arguably represent this first phase of the composer’s seven-stage grieving process over hearing loss. Interestingly, his compositions during this span of years, despite debilitating prescience about the inevitability of the future, are disarmingly optimistic, full of energy, innovation, color, and heroic valor. Denial? Cover up? Whatever the motives behind these compositions, subconscious or otherwise, they all speak magnificently to the composer’s resolve in the face of adversity.

The two last movements of the Symphony No. 4, Menuetto – Allegro vivace, and Allegro ma non troppo, are the musical embodiment of youthful hope, resilience, and vigor. Playfulness is king-of-the-mountain in both movements, but particularly the last, which begins at a thrilling tempo, then barrels forward with additional breathtaking speed and energy. Clever compositional nods to Haydn – Mannheim rockets, coy rhythmic and harmonic dodges – charge this happy musical cyclone toward a full throttle finish, notwithstanding one last sneaky Haydnesque deception just before the sudden and much faster last few bars. Out of adversity, strength!

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the program notes

Download a PDF of Joshua Sobol’s text to The Eternal Stranger

Santa Barbara Symphony program notes February 18-19 2023: Transformation

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony website

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit saxophonist/composer Ted Nash’s website

Visit the Josh Nelson Trio website

Visit pianist Natasha Kislenko’s bio page

Read my review of the February 18 2023 concert

Transformation

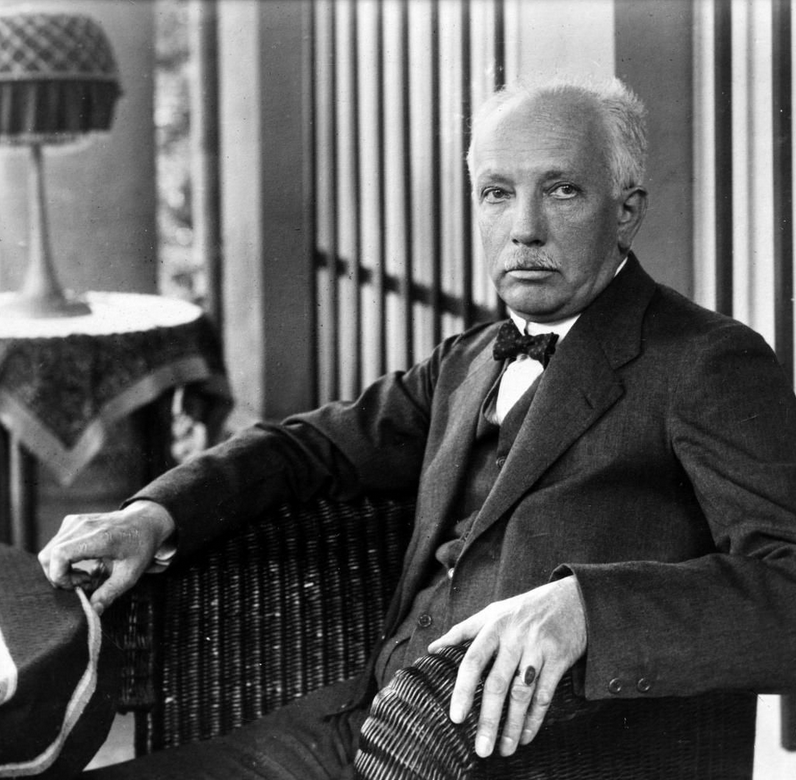

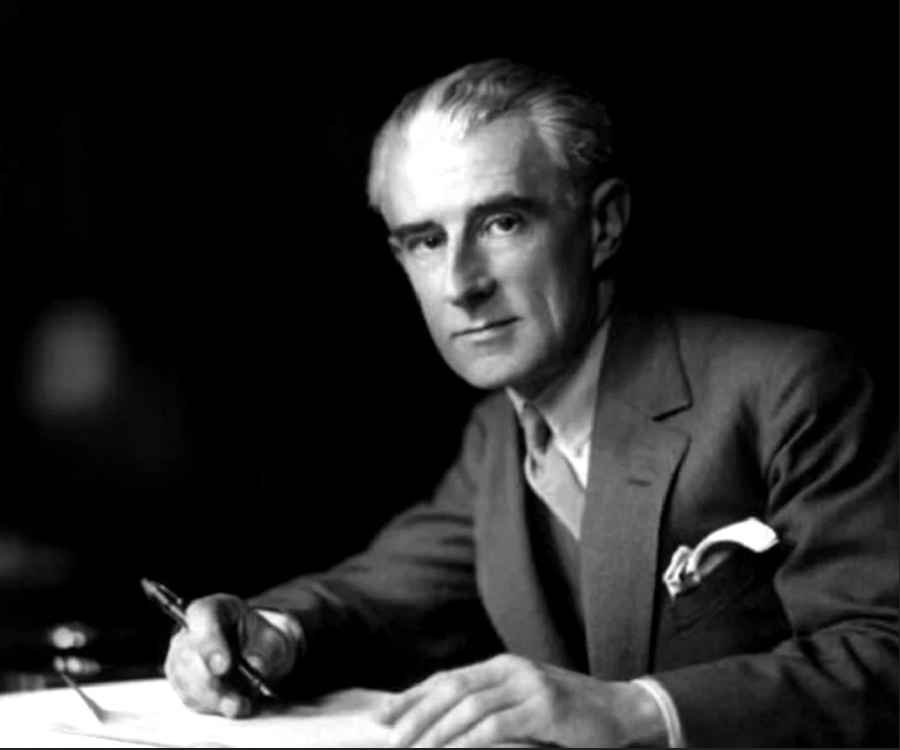

There are several kinds of transformation; animal, vegetable, mineral, musical . . . Conductor Nir Kabaretti has set himself the task of illustrating two levels of transcendental experience with four works on the February 18 and 19 concerts. Variations on a Nursery Song for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 25 (1914) by Hungarian composer Ernst von Dohnányi (1877-1960) opens each concert, and Boléro (1928) by Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) serves as the final work on each program. These two pieces represent physical/mechanical metamorphoses - simple tunes morphed into complex and imaginative orchestral masterpieces through human intellect and the techniques of composition and orchestration.

Nestled between the Dohnányi and Ravel, a fresh re-thinking of jazz saxophonist/composer Ted Nash’s 2021 collaboration with actress Glenn Close, Transformation: Personal Stories of Change, Acceptance, and Evolution (2021) In its new incarnation called simply, Transformation, together with the tone poem Death and Transfiguration, Op. 24 (1888-1889) by German composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949). These two works speak through different musical prisms and centuries to mysteries psychological and spiritual about human transition and re-birth. Strauss meditates on unconscious, mystical transformation, while Nash’s Dear Dad, one of four sections in his new Transformation suite, is about conscious, purposeful transition. Together, the four works on this program offer our minds and ears thought-provoking examples of physical and metaphysical change.

The concerts open with Ernst von Dohnányi’s Variations on a Nursery Song for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 25 (1914). The composer’s subtitle, scribbled on his manuscript score but never published reads, “For the enjoyment of friends of humor, to the annoyance of others,” an admonition that is not to be taken lightly about one of the great orchestral brain twisters of the early twentieth century. Dohnányi uses as his creative inspiration the nursery song, Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star, a tune that seems in historical retrospect rather whimsical and naïve, a prescient if unconscious farewell to the innocence of antebellum Europe on the brink of World War I.

Born in 1877 in Bratislava, Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia), Dohnányi enrolled at the Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music in Budapest at age 17 in 1894, graduating in piano and composition in 1897. After World War I, Dohnányi served periodically over the next 20 years as Director of the Budapest Academy of Music and conductor of the Budapest Philharmonic. Unassailable in matters ethical as well as musical, by 1941 Dohnányi had no choice but to resign his post at the Academy of Music rather than submit to anti-Semitic legislation that denied Jews with musical talent entry. By 1944 when Germany occupied Hungary, Dohnányi had assisted hundreds of Jews to escape the Nazis. German occupation the final blow, Dohnányi disbanded the Budapest Philharmonic rather than fire only the orchestra’s Jewish players.

After World War II the composer and his wife moved to Florida, where they received American citizenship in 1955 while he taught at Florida State University School of Music. He died in New York City on February 9, 1960, just days after conducting Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 with his doctoral student as piano soloist. This concerto had been Dohnányi’s signature touring piece as an international soloist in his youth. A sweet way (prescience?) to take leave of the planet.

Variations on a Nursery Song caricatures with tongue-in-cheek compositional guile, several composers with whom late-Victorian, early modern European audiences would have been familiar circa 1914, like Tchaikovsky and Ravel among others. Disguised fragments from these composers’ works, or playful parodies of the compositional styles of other composers, have been puzzled carefully by the composer into his eleven variations on the nursery song Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. Finding these sly musical clues, let alone discovering traces of Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star in the variations, serves as the composer’s gentle last laugh with audience and scholars, alike. Variations on a Nursery Song, like Elgar’s Enigma Variations, is one of the most complex Rubik’s cubes in the repertoire.

A virtuoso tour de force for orchestra, the piano “obbligato” is in every way but name, a concerto. Keeping in mind, Dohnány was one of the great piano virtuosos of his time, the piano riffs - amusing, coy, playful, virtuosic – are not to be taken lightly. Continuing Lecturer in Keyboard at UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Music, collaborative faculty member at the Music Academy, and Santa Barbara Symphony Principal Pianist, Natasha Kislenko, is the capable soloist for Dohnányi’s devilishly virtuoso piano hijinks.

“We wanted to create an evening around the transition from darkness to light, from despair to hope, from hatred to forgiveness,” explained Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild Awards winning actress, activist, and jazz lover Glenn Close, during a video chat in New York City (https://youtu.be/ReuTZFKZ1bg) with Los Angeles-born jazz saxophonist and composer Ted Nash in 2019 about their collaboration in words and music, Transformation: Personal Stories of Change, Acceptance, and Evolution. Progeny of a well-known family of jazz and studio musicians in Los Angeles, Ted Nash has become one of the most significant jazz composers of the 21st century. He is co-founder of the New York-based Composers Collective and is a long-standing member of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis.

Nash composed the music for Transformation while Close found pertinent texts and stories about transformative experiences she could narrate to “inspire, and basically comfort our audience.” The Jazz at Lincoln Center live show was cancelled because of COVID, but a CD was released in 2021 of Transformation: Personal Stories of Change, Acceptance, and Evolution.

Two years later enter Nir Kabaretti and the Santa Barbara Symphony with the composer himself on solo saxophone, joined by the Los Angeles-based Josh Nelson Trio, to perform Nash’s new version of Transformation, including two new pieces, and the world premiere of Nash’s extensive orchestrations. Four segments make up the reincarnated version of Transformation. The only piece remaining from the original 2021 concept is Dear Dad, a letter from Nash’s son Eli to his father, this time fully orchestrated with sax soloist, jazz quartet, and narrator.

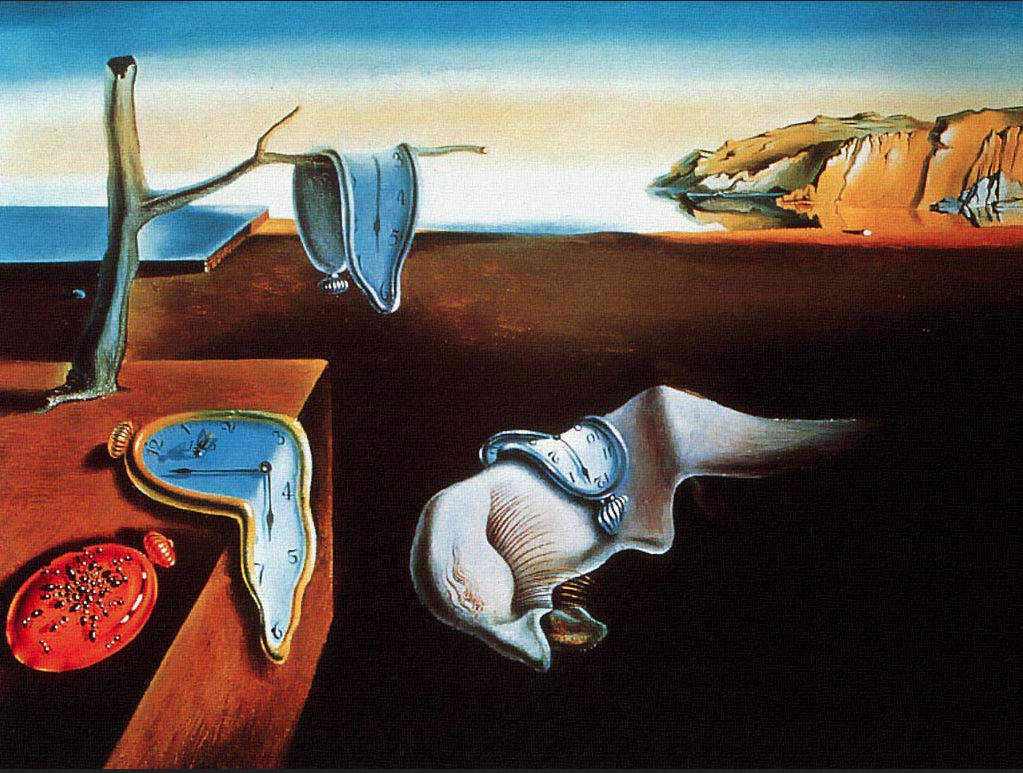

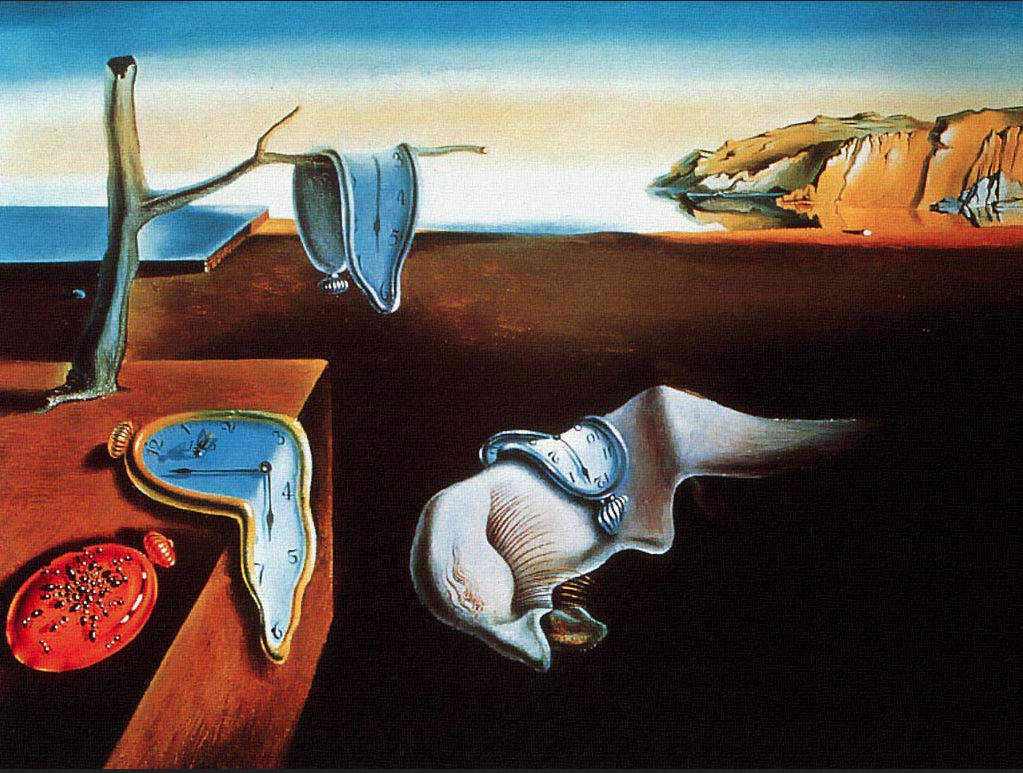

“One of the things I’m going to do with this piece is bend time,” Ted Nash explains about the world premiere of his new orchestration for Transformation, of Dali, a movement from his Portrait in Seven Shades composed for Jazz at Lincoln Center a few years back. Focusing on Dali’s eponymous canvas, The Persistence of Memory, with its melting clocks on a barren landscape, Nash does indeed bend time with his musical interpretation. “Through music, I want people to experience this iconic image in a new way,” Nash explained at the time. Now, in its fully orchestrated version, Dali dazzles the imagination even more.

The remaining two pieces in Nash’s new version of Transformation, Wolfgang’s Samba and Scriabin Prelude, Op. 11, No. 1, take existing melodies, in this case Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet and the Scriabin Prelude, and re-imagines them in a jazz/orchestral idiomatic mash up. “We will go back and forth from full orchestra to a jazz quartet with improvised solos,” the composer explains.

Composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist Richard Strauss (1864-1949), a leading representative of the German late Romantic and early modern periods, had a special knack for tone poems; descriptive musical narratives that tell big stories in one continuously flowing movement. Of his eight tone poems, the first two, Don Juan, Op. 20 (1889) and Death and Transfiguration, Op. 24 (1888-1889) are arguably the most profound. The protagonist in Don Juan is a libertine who wills his own death. Yet after its premiere Cosima Wagner, widow of Richard Wagner (1813-1883) whose operas Strauss learned and loved in his job as assistant conductor in Bayreuth under her sovereignty as heir to Wagner’s vision, found the story lacking the high metaphysical ideals of her husband.

Strauss’ second tone poem was his answer to Cosima Wagner’s high-handed criticism of Don Juan. Death and Transfiguration depicts the psychological travail and journey of a man dying; his thoughts on life and its struggles disturbing his peace of mind, until he receives deliverance from mortal life by transfiguration “from the infinite reaches of heaven.” In four parts woven together as one continuous musical fabric, the composer asks then, as he did 60 years later, using the same Transfiguration motif in At Sunset, from Four Last Songs (1948), “Is this perhaps death?” A year after Four Last Songs and on his own deathbed, Strauss said to his daughter, "It's a funny thing Alice, dying is just the way I composed it.”

French Impressionist composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) wrote a friend in 1924 that he was contemplating composing “a symphonic poem without a subject, where the whole interest will be in the rhythm." The very idea would have sent the imperious Cosima Wagner into a tailspin. Ravel was a revolutionary thinker and musical innovator as well as a rather sly fellow about his messaging, especially after the horrors of World War I. His tone poem Boléro (1928) which closes the concerts on February 18 and 19, is arguably the most successful exercise in sonic erudition in the history of music. Even the composer was amazed at the instant success of the piece.

On a more subtle, post WW I level of cognition, Boléro is also a brilliant musical slap in the face of antebellum romanticism, suggesting in its final cataclysmic bars, the end of the old order.

Literally a transformation by volume, Boléro begins with a tiny rhythmic figure on snare drum, pianississimo, which never changes over the course of the piece except in heft (added percussion). An alluringly mellifluous tune floats above the steady rhythmic pattern, also never changing but growing slightly larger in volume (orchestration) each time it repeats. An inverse pyramid of orchestral magic is achieved, the lightweight and barely audible rhythmic figure played on the edge of a snare drum, eventually supporting a massive sound structure carefully assembled by adding instruments bit by bit. Like a house of cards, or the end of monarchical Europe, the hulk eventually collapses of its own artificial weight, Boléro’s brilliantly chaotic last seconds graphically illustrating the catastrophe.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the program notes

Santa Barbara Symphony program notes January 21-22 2023: Plains, Trains & Violins

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit composer Elmer Bernstein’s website

Visit guitarist/composer/arranger Peter Bernstein’s website

Visit composer Miguel del Águila’s website

Read my review of the January 21 2023 concert

Plains, Trains & Violins

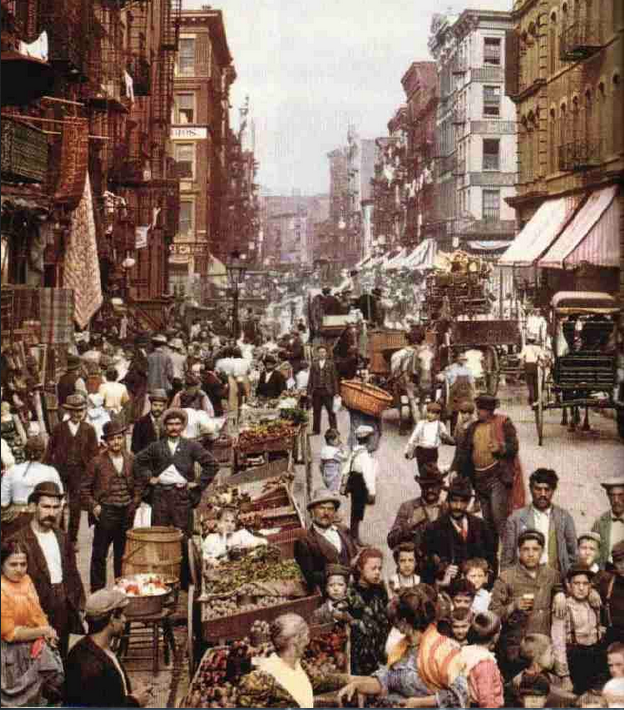

Season 2023 opens January 21st and 22nd with a program that speaks eloquently to the history of human migration on our planet, especially in the last two centuries. Conductor Nir Kabaretti has crafted a musical experience that speaks with bittersweet poignancy to the vast movement of peoples and cultures sparked worldwide, by the Industrial Revolution (1750-1914) that continues to this day.

Rapid advances in public transportation - trains in particular – is the concert’s narrative backstory and topic of the first piece, Peter Bernstein’s orchestration for the Santa Barbara Symphony (world concert premiere) of his father Elmer Bernstein’s charming score to the 1950’s stop-action animated film, Toccata for Toy Trains. Violinist Guillermo Figueroa joins maestro Kabaretti to explore Miguel del Águila’s evocative Concerto for Violin, El viaje de una vida (The Journey of a Lifetime) with its own unique migration story to tell. Crowning the concert’s subtle and inspiring messaging about diversity, one of the greatest musical insights into American multiculturalism ever penned by a visiting foreigner, Dvořák's New World Symphony.

Long time Santa Barbara Resident before moving to nearby Ojai in his last years, American composer Elmer Bernstein (1922-2004) was one of the most highly regarded film composers of his era, composing scores for over 150 major movies including blockbusters like The Ten Commandments, The Great Escape, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Magnificent Seven.

A graduate of New York University and The Juilliard School, Elmer Bernstein was blacklisted during the McCarthy era in the early 1950’s. For a period of years during that bleak time in American history, the composer accepted lesser jobs to cover rent and groceries, composing music for cheesy monster movies, TV shows, and commercial documentaries.

The composer was nurtured artistically during those blacklist years by collaborations with Charles and Ray Eames, the world-famous mid-century husband and wife furniture and architecture design team. The Eames’ produced around 125 short art films focused on various of their many passions, including antique toy trains. Bernstein was employed to write the music for several of their shorts, including a film about toy trains.

Toccata for Toy Trains (1957) which can be seen on YouTube, is a stop-action animation fantasy of about 14 minutes, shot from a toys-eye-view with a whimsical opening narrative by Charles Eames himself, about the subtle artistic differences between antique toy trains and mere model trains. Most of the trains, automobiles, people, towns, and train stations in the film date to the late nineteenth century, the very heartbeat of the Industrial Revolution.

Elmer Bernstein’s son Peter, a professional jazz guitarist and film composer in his own right, has expanded his father’s original Toy Trains score written for eight players to the full orchestral capabilities of the Santa Barbara Symphony. In doing so, this charming score will now enjoy the wider audience it deserves.

Fleeing Uruguay’s repressive military government in 1978, Miguel del Águila immigrated to the United States and in time, received his American citizenship. Graduating from the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, he attended the prestigious Hochschule für Musik in Vienna, returning to the US in 1992 (Ojai, California). He now lives in Seattle. Águila has enjoyed three Latin Grammy nominations in recent years for his compositions and has served as composer in residence with orchestras in America and around the world.

Miguel del Águila’s Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 94 El viaje de una vida – The Journey of a Lifetime, was commissioned by the New Mexico Symphony in 2007 and premiered by that orchestra with its music director, violinist Guillermo Figueroa as soloist in 2008. Figueroa is guest artist for these Santa Barbara Symphony performances of the Violin Concerto – a real treat.

Águila assigns the violin soloist the role of traveler and protagonist in his musical narrative. Abandoning the homeland (Spain) for South America in the first movement, Cruzando el océano hacia un nuevo mundo – Crossing the Ocean to a New World, Águila describes the Atlantic crossing in music; a soundscape as vast and expectant as the sea itself. The second movement, En la tierra púrpura – In the Purple Land, is a somewhat withdrawn and somber narrative, suggesting the melancholy style of the Vidalita, a slow and nostalgic song of the Uraguayan gauchos; the music a sensual conversation between soloist and orchestra.

The brief third movement, El regreso – The Return, depicts an imagined return to Spain by the traveler years later to confront his past, which segues without pause into the fourth movement, Jota-Finale. Initially in a light mood, the concerto ends with a dramatic confrontation between soloist and orchestra (the traveler and the outside world) as the immigrant realizes that one can never return to the same place. What was left long ago, is lost forever.

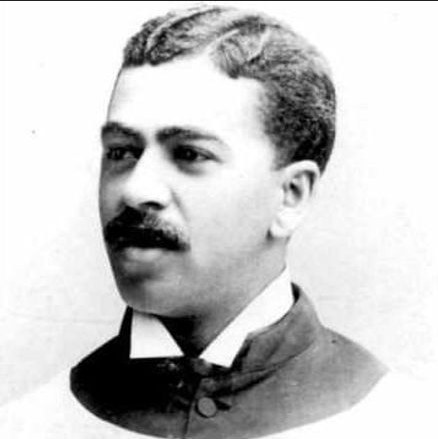

Violinist/conductor Guillermo Figueroa is the Principal Conductor of the Santa Fe Symphony, Music Director of the Music in the Mountains Festival in Colorado, and the Lynn Philharmonia in Florida. He has served as Music Director of both the New Mexico Symphony and the Puerto Rico Symphony. At The Juilliard School, his teachers were Oscar Shumsky and Felix Galimir. His conducting studies were with Harold Farberman in New York.

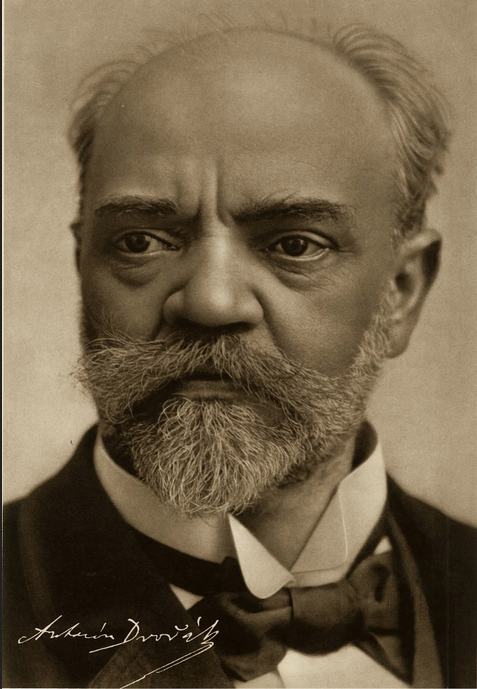

Bringing the program’s immigration saga full circle, philosophically as well as musically, maestro Kabaretti has programmed Czech composer Antonín Dvořák's musical masterclass on the subject, the Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 From the New World, composed in 1893 while the composer was in America (1892-1895) serving as director of the National Conservatory of Music (1888-1920) in New York City.

Invited by the National Conservatory’s founder, Jeannette Meyers Thurber, a philanthropist who championed the rights of women, people of color, and the handicapped throughout her life, Dvořák experienced first-hand during his five- year stay, an America that was prosperous post-Civil War, and poised to become, for better or worse, a great power on the world scene. The promise of the Statue of Liberty’s pledge was still fresh. Immigration to America was at an all-time high in the 1890’s.

Westward expansion, thanks to the transcontinental railroad, was opening the interior of the country to vast new settlement lands. The United States, having won its “Indian Wars” with a final slaughter of Native Americans at Wounded Knee (1890), was on the cusp of its Imperialist moment; wealth in resources, commerce, and human energy was clearly visible everywhere Dvořák travelled.

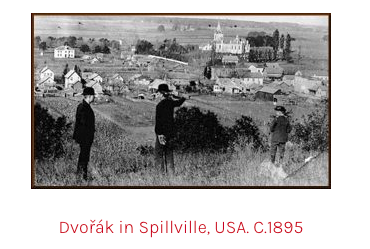

At Jeannette Thurber’s suggestion, the composer titled his eye-witness musical snapshot of America, “From the New World,” completing the Symphony No. 9 during his second year in-country (1893) literally completing the manuscript in the middle of nowhere, tiny Spillville, Iowa, whose population in 2020 was only 385, but which had a thriving, if also small Czech immigrant community in the 1890’s

A stunning musical diary of what he saw and heard, but more importantly, what he intuited from the vibrant and rambunctious new republic, Dvořák’s is a narrative not so much about the immigrant journey to America, as the positive impact of immigration on the vibrancy of American democracy; a reverse musical postcard to the Old World, from the New.

Commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, the New World Symphony was premiered by the orchestra on December 16, 1893 and has been popular the world over ever since. In an interview with the New York Herald the day before the premiere, Dvořák minced no words. “I am satisfied that the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called the Negro and Indian melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America, and your composers must turn to them.”

In the standard late romantic symphonic form of four movements, From The New World is entirely Dvořák’s original music. “I have not actually used any of the [Native American] melodies,” he said during another interview at the time. “I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of the music, and using these themes as subjects, I have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, counterpoint, and orchestral color.”

The first movement, Adagio – allegro molto, especially its rousing horn tune, exemplifies the vigorous young nation of possibilities and energy the composer witnessed during his travels in America. The second movement, Largo, with its iconic English horn solo, is the key to understanding the deeply human subtext of the work. The composer decided on that instrument’s color because it reminded him of the famously bittersweet baritone voice of his African American composition student at the National Conservatory, Harry Burleigh (1866-1949). Burleigh was instrumental in developing a characteristically American classical music genre. His ideas had a profound influence on Dvořák’s thoughts about the importance of African American and Native American musical culture as the founding stone of the “New World” experience.

The third movement, Molto vivace, opens with a lively quadrille which eventually melds into a charming original folk tune inspired, according to the composer, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, Hiawatha: To the sound of flutes and singing, To the sound of drums and voices, Rose the handsome Pau-Puk-Keewis, And began his mystic dances. The last movement, Allegro con fuoco, is a visionary musical anticipation of the American century ahead; a heroic toast to the success of the greatest immigrant experiment in human history – the United States.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the program notes

Santa Barbara Symphony program notes November 19-20 2022: Wisdom of the Sky, Water, Earth

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit composer Cody Westheimer's New West Studios website

Visit pianist Alessio Bax’s website

Read my review of the November 19 2022 concert

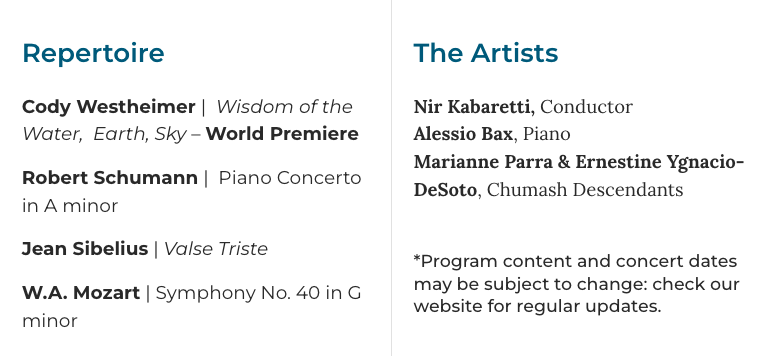

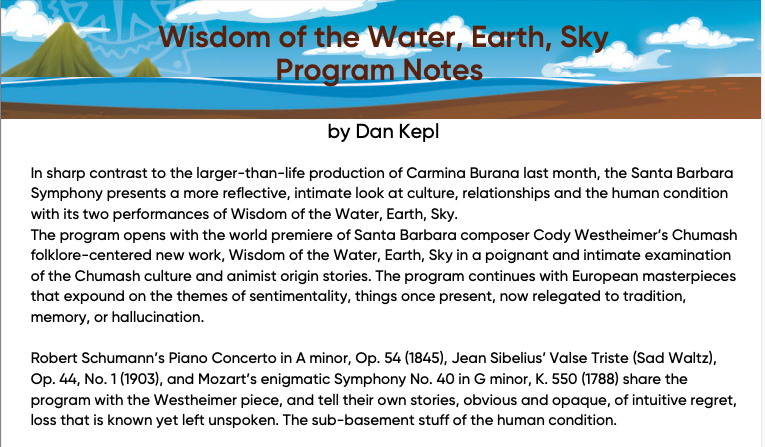

Wisdom of the Sky, Water, Earth

A dusting of bittersweet sadness worries conductor Nir Kabaretti’s musical choices for the November 19 and 20 concerts. Partnering with the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History and the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, the world premiere of Santa Barbara composer Cody Westheimer’s Chumash folklore-centered new work, Wisdom of the Sky, Water, Earth, is an examination of the tribe’s culture and animist origin stories. European masterpieces on the program also address loss; things once present, now relegated to tradition, or memory, or hallucination.

Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54 (1845), Jean Sibelius’ Valse Triste (Sad Waltz), Op. 44, No. 1 (1903), and Mozart’s enigmatic Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 (1788) share the program with the Westheimer piece, and tell their own stories, obvious and opaque, of intuitive regret, loss that is known yet left unspoken. The sub-basement stuff of the human condition.

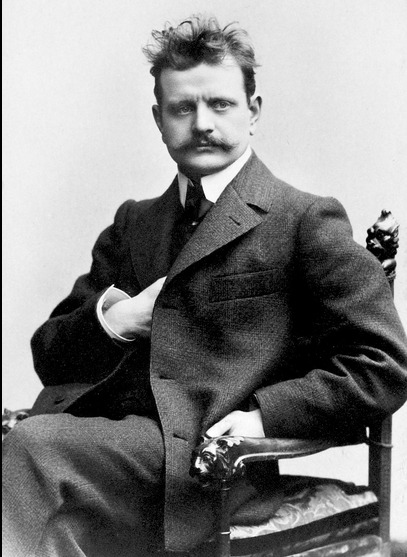

Robert Schumann’s gift to his beloved Clara, the Piano Concerto in A Minor, cannot escape, for all its energy and celebration, the poignant presence of self-doubt, perhaps a foreknowledge in 1845 the year of the concerto’s composition, of the inevitable outcome of the composer’s debilitating struggle with depression and insanity that ultimately led to his suicide in 1856. Jean Sibelius’ Valse Triste (Sad Waltz), Op. 44, No. 1 (1903) is a heartbreaking tale of loneliness, aging, and abandonment. It is also one of the most beautiful short works for small orchestra in the repertoire.

An alcoholic, Sibelius knew of sadness, and the melancholy tonal temperament of Valse Triste is, like the composer’s alcoholism, a slow waltz with death. Mozart’s “Great” G minor Symphony No. 40, K. 550 (1788) composed three years before his passing in 1791, gives up some of its secrets in plain sight, like its key of G minor, a red flag for tonal sadness. Like the A minor tonality in the Schumann concerto, these two minor keys are used with purpose by composers to express unhappiness. In 1788 Mozart’s bills were a tsunami, while ticket sales for his performances were slacking off; plenty of reason to be bummed.

Santa Barbara-born composer Cody Westheimer (1979-), whose first serious orchestral composition was premiered by the Santa Barbara Symphony when he was 17, has an impressive portfolio of music he has composed for feature films, documentary series, and iconic sports events, like his Tour de France theme on NBC. While at USC's Thornton School of Music he composed the music for nearly 40 short films, and graduated Magna Cum Laude in 2001, while concurrently completing USC's Film Score Certification program. Since then, he has written hundreds of hours of music for independent narrative features, documentaries, network and cable television shows, movies, and video games.

Now living once more in Santa Barbara, Westheimer is an avid environmentalist, land preservationist, and nature photographer, in addition to his work as a composer. Westheimer has engaged with the Chumash people on various environmental projects over the years. The commission to compose a World Premiere piece of musical and narrative art honoring the Chumash and their rich heritage of ancient Wisdom of the Sky, Water, Earth, is a particular honor for the composer.

Through-composed like a tone poem, Wisdom of the Sky, Water, Earth has six discernible sections within its one-movement format: Introduction; Water: Dolphin; Earth: Deer; Earth: Squirrel; Sky: Hawk; and Epilogue. “The music is sculpted by my perception of their personalities,” Westheimer explains of the four animals and their profound messages to mankind. Each Chumash parable will be read in English and Chumash by tribe descendants, Marianne and Ernestine. “These Chumash people’s stories have served as creative inspiration for my music and have tremendous relevance today,” Cody shared. “The first people on this land got it right, we must learn from and honor their legacy.”

German composer Robert Schumann (1810-1856) enjoyed a major career as a music critic, literary authority, and virtuoso pianist in addition to his output as a composer, but his path to success was slow to kick in and short-lived. A child of the Napoleonic catastrophe in Europe (1803-1815) he experienced the destruction, displacement and chaos, both psychological and physical, wrought by the nineteenth century’s first world war. Wellness and career became a constant struggle for the composer, ending sadly, in insanity and suicide by 1856.

Studying piano with Friedrich Wieck, Schumann fell rather compulsively in love with Wieck’s daughter Clara, herself a brilliant concert pianist/composer. In her father’s eyes, Schumann was not financially adequately stable to marry and support his daughter, refusing entreaties to permit marriage. A battle royale between Robert Schumann and Friedrich Wieck wracked its way through several years of nastiness and litigation. Finally in 1840, Robert and Clara married.

Finished in 1845, the composer’s wedding gift to his wife, the Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, is one of the most widely performed piano concertos in the repertory of the Romantic period. The first movement, Allegro affettuoso, was played publicly as early as 1841, and is a stand-alone powerhouse of abundant melody and gushing passion in adoration of his wife’s tremendous talent.

Still, interrupting at least one of several churning passages of exhilaration, a nearly funereal tune in oboe and horns, soon dispelled but nevertheless haunting; a “nagging headache” of premonition, as the composer would describe the first onset episodes of his mental collapse.

It’s hard to imagine a better way to express love between two people than the second movement of the work, Intermezzo – Andantino grazioso, which breaks all previous rules about what a second movement in a three-movement concerto from that period should be. Traditionally slow, quite often an Adagio, Schumann expresses his love for the beloved Clara with a lighthearted and flirtatious movement, gushing, swooning, taking walks in the park hand in hand, the musical imagery is unmistakable.

The movement segues like butter on hot toast directly into the last movement, Allegro vivace, which confidently states the composer’s love for his wife in grand postnuptual manner, particularly the magnificent coda and last big brass chord at the very end, à la Berlioz.

Pianist Alessio Bax has been a regular and favorite guest artist in Santa Barbara for several years. Settling in the United States in 1994, Bax lives in New York City with his pianist wife, Lucille Chung and daughter Mila. He has been a member of the piano faculty at Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music since 2019. Awarded an Avery Fisher Career Grant in 2009, and four years later both the Andrew Wolf Chamber Music Award and the Lincoln Center Award for Emerging Artists, Bax tours throughout the world on a regular basis as a chamber music colleague and concerto/recital soloist.

Originally one of a six-movement set of incidental pieces for small orchestra Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) composed in 1903 for a rather gruesome play, Kuolema (Death), by his brother-in-law Arvid Järnefelt, Valse Triste (Sad Waltz), Op. 44, No. 1, immediately took on a life of its own as an independent concert piece, and has remained popular to this day.

Despite its rather depressing portrait in music of a bittersweet last waltz shared with already dead friends who appear during the final delirium of a dying woman’s life, Valse Triste begins delicately, and sustains beautifully, a languorous, sadness-tinged waltz tune that mesmerizes. There are occasional bursts of energy as the woman tries to maintain her failing energies, then a final, frantic dervish before the dying woman collapses and the piece fades away. Easily among the most famous and frequently performed of his works, Sibelius was cheated of his royalties for Valse Triste.

Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) likely died of renal failure exacerbated by the stress of his last, poverty-chased years. As the programmatic superstructure of this Santa Barbara Symphony concert pair so poignantly illustrates, stress, unhappiness, regret, and loss often produce great art. Mozart’s last years, while troubled, saw the creation of a considerable number of his most compelling masterpieces, including the Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 (1788), composed three years before his death.

Like so many artistic works created by humans under personal or cultural stress, the opposite emotion is often expressed. The Symphony No. 40 is a masterpiece of joy and innovation on its surface, though tinted in the colors of the more introverted, darker tonality of G minor. There are other subtle indicators of a troubled subtext, including readily identifiable orchestral sighs that characterize the rhythmic pulse of the first movement, Molto allegro, and the solemn pace and funereal dotted rhythms of the second movement, Andante. The third movement, Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio, while delightfully animated and light, is concurrently insistent and aggressive, mellowed only by the delicacy and slower tempo of the movement’s Trio section. Segueing immediately into the last movement, Finale – Allegro assai, Mozart creates another of his signature compositional finale’s, sparkling with brilliant jollity, clever invention, and intricate contrapuntal devices.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the program notes

Santa Barbara Symphony program notes October 15-16 2022: Carmina Burana - Song, Dance & Symphony

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit State Street Ballet

Visit choreographer William Soleau’s website

Visit Santa Barbara Choral Society

Visit Quire of Voyces

Visit Music Academy Sing! Children’s Chorus

Read my review of the October 15 2022 concert

Carmina Burana – Song, Dance & Symphony

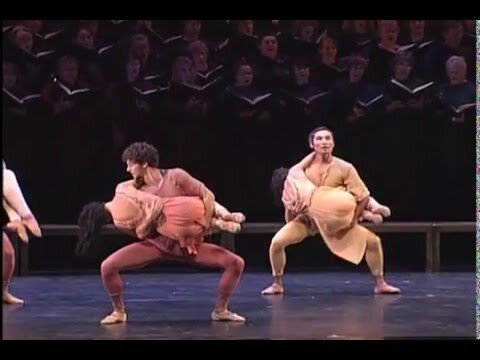

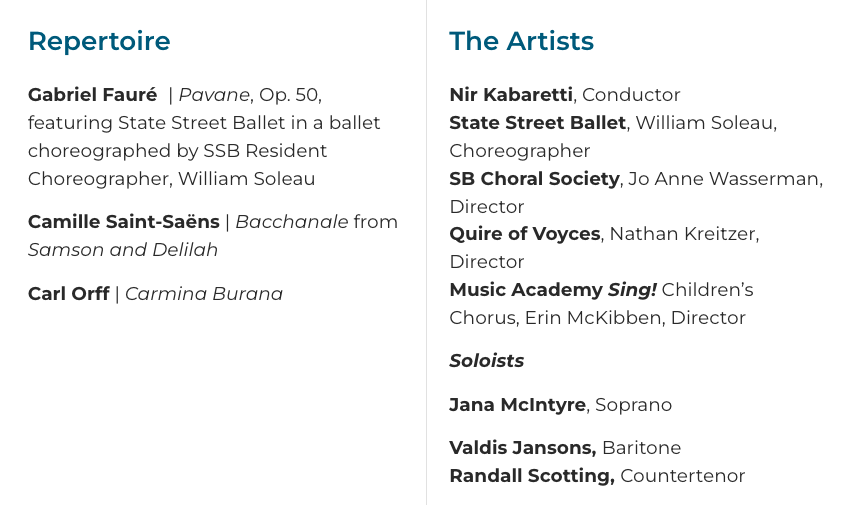

Decadence is fun, as Santa Barbara Symphony Music and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti demonstrates with an exhilarating season-opening curation of music celebrating the launch of the orchestra’s 70th season. In collaboration with State Street Ballet and The Granada Theatre, also featuring the Santa Barbara Choral Society (Jo Anne Wasserman, Director), Quire of Voyces (Nathan Kreitzer, Director), and the Music Academy’s Sing! Children’s Chorus (Erin McKibben, Director), there’s good reason to party hearty after two years of intermittent lock downs and empty theaters. The opening concert of the 2022-2023 Santa Barbara Symphony season October 15 and 16 also rekindles a cherished collaborative tradition between the city’s major music, dance, and choral groups that began in 2015 with the first co-production of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana.

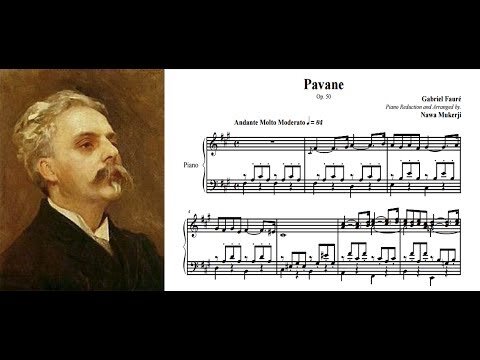

The party begins in leisurely manner, with one of French composer Gabrielle Fauré’s most popular works, the Pavane in F-Sharp minor, Op. 50 (1887). Performed by orchestra, chorus, and dancers in the manner of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes production of 1917, State Street Ballet Co-Artistic Director and Resident Choreographer, William Soleau, has crafted new choreography for the piece. Waxing decidedly more sensuous, maestro Kabaretti and the orchestra follow the Pavane with a bacchanale, Camille Saint-Saëns’ pulse-quickening, natives-in-heat scene from his opera, Sansom and Delila (1877).

The Fauré and Saint-Saëns are but warmups for the blockbuster grand finalé of the concert, German composer Carl Orff’s monumental paean to fate, fortune, springtime, eroticism, and roasted swan, Carmina Burana (1936). Dusting off and refreshing William Soleau’s choreography from the 2015 collaboration, this reunion will find the various participating ensembles eager to make music again as a collective. It’s no secret the Symphony, State Street Ballet, Santa Barbara Choral Society, Quire of Voyces, and Sing! Music Academy Children’s Chorus are prepared to deliver an exciting performance that will be long remembered.

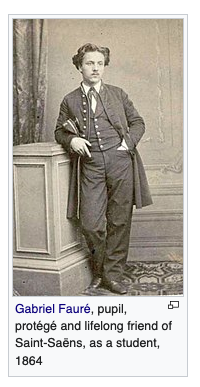

Inspired by the Medieval Spanish processional court dance of the same name, the Pavane in F-Sharp minor, Op. 50 (1887) by French composer Gabrielle Fauré (1845-1924) quickly became one of the composer’s most popular works. Originally a piano piece, Fauré envisioned additional exposure and cash flow by arranging the Pavane for other instrumental groupings including orchestra. Dedicating the piece to his patron, Elisabeth Comtesse Greffulhe, Fauré decided to glam it up a bit more, adding an offstage chorus singing forgettable verses by the Comtesse’s cousin. Fauré even allowed for the possibility of dancers, should his patron have relatives in the Paris Opera corps de ballet.

Kabaretti, seeing advantage in the unique forces at his disposal for this concert, has staged Pavane as it has seldom been seen and heard, with members of State Street Ballet onstage to interpret Co-Artistic Director William Soleau’s new choreography, and an offstage chorus to bring full circle, Fauré’s grand vision for the piece.

It's a small world, and maestro Kabaretti enjoys exploring human connectedness in his programming. French composer Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) was a musical prodigy, making his debut as a concert pianist at the age of ten. A virtuoso organist as well, though he didn’t like church gigs much, the composer payed the rent for most of his life primarily as a freelancer teaching piano to among others Gabrielle Fauré, writing music and theater reviews, and composing.

At first a champion of nineteenth century modernity, particularly the music of Wagner and Liszt, the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) in which Saint-Saëns served as a member of the French National Guard, soured his enthusiasm for things Germanic. His music became more conservative, melancholy, and occasionally outright cynical, focusing internally as well as nationalistically on French composers including his student Gabrielle Fauré.

In 1877 Saint-Saëns achieved a personal composing milestone with his opera Samson and Delilah. Parisian audiences and critics of the Victorian era trashed the opera for daring perhaps obscenely, to portray Biblical characters. Ironically, and on the recommendation of Liszt, the opera was staged successfully that same year in Germany. A Paris production in 1890 finally won French public acceptance, and Sansom and Delilah has since become the composer’s most famous and popular opera.

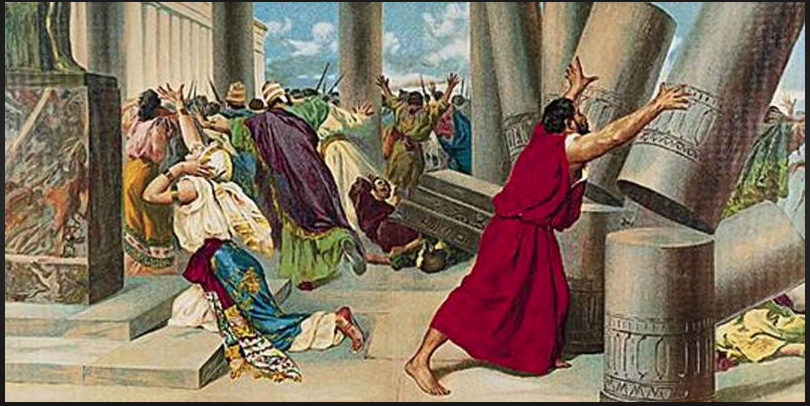

The Bacchanale scene from Samson and Delilah takes place near the end of Act III. A choreographic scene of slithering dance debauchery for the opera’s corps de ballet, scantily clad revelers led by Delilah herself, celebrate the downfall of Samson, losing themselves to the intoxicating percussion-driven dance of triumph and lust. The chained and humiliated Sansom musters one last surge of strength and brings down the Philistine temple upon himself and his godless torturers. The famous “snake charmer” tune which mesmerizes and motivates the entire scene, has become an eponymous tune of seduction.

Munich-born German composer Carl Orff (1895-1982) like Fauré and Saint-Saëns, was traumatized, psychologically and physically, by war. Saint-Saëns was a member of the French National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War, Fauré fought for the French during World War I, Carl Orff, descended from a distinguished German military family, was conscripted into the Imperial German Army in 1917, receiving severe injuries in a trench collapse.

During the Nazi regime and through World War II Orff remained in Germany, composing prolifically, while ducking membership in the Nazi Party. His 1936 masterpiece for chorus, soloists, and orchestra, Carmina Burana, one of a triptych of choral works using original texts from the 11th to 13th centuries examines cynically, bothersome issues Orff himself had lived through during the First World War, Weimar Republic, Germany’s Great Depression, and the rise of fascism: fickle fortune, equally fickle wealth, drinking, gluttony, gambling, lust, and death.

Immediately popular after its debut at Frankfurt Opera in 1937, Orff’s “scenic cantata” was performed throughout Germany before World War II, and after the war worldwide. Consisting of 25 movements, divided into five major sections (a musical structure like a giant wheel of fortune), Carmina Burana is the musical progeny of an Orff concept, Theatrum Mundi – music, movement, and speech, connected to an action on stage. With conductor Nir Kabaretti’s leadership from the podium and William Soleau’s beautiful choreography important ingredients in the mix, these performances of Carmina Burana by the Santa Barbara Symphony, State Street Ballet, Santa Barbara Choral Society, Quire of Voyces, and the Music Academy’s Sing! Children’s Chorus will fully realize Orff’s Theatrum Mundi purpose for the work.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the program notes