Santa Barbara Symphony program notes May 13-14 2023: Platinum Sounds

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit violinist Philippe Quint’s website

Visit composer Jonathan Leshnoff’s website

Read my review of the May 14 2023 performance

Platinum Sounds: The Symphony Turns 70

The May 13-14 2023 concerts celebrate the orchestra’s 70th anniversary season with a particularly thoughtful program. Conductor Nir Kabaretti looks at juxtapositions; past, present, and future. Opening with a work commissioned by the orchestra to mark its 60th birthday, American composer Jonathon Leshnoff’s Concerto Grosso (2012), Kabaretti next turns the spotlight on a guest artist who last appeared with the orchestra in 2017, Russian-born American violinist Phillipe Quint. Felix Mendelssohn’s cheerfully enigmatic Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1838-1844) is the centerpiece for Quint’s return visit. Bringing the concert to a properly platinum close, maestro Kabaretti channels the Classical Period (Mozart, Haydn) through the lush, late romantic polyphony of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 (1855-1876).

Baltimore-based American composer Jonathan Leshnoff (1973-) has become one of the most widely performed composers in the world. Described by the Baltimore Sun as “cohesively constructed and radiantly lyrical,” Leshnoff’s enormous portfolio of symphonies, oratorios, chamber music, and concertos have consistently satisfied concert audiences without compromising compositional integrity for popular accessibility.

After conversations between conductor Nir Kabaretti and the composer, the Santa Barbara Symphony commissioned Leshnoff in 2012 to compose a work that would feature several of the orchestra’s principal players. Concerto Grosso in the Baroque Style, modeled after the Baroque concerto grosso form, was given its premiere in Santa Barbara’s Granada Theatre on March 16-17, 2013.

Highlighting ten principal soloists from the orchestra during its four movements, the first movement, Allegro, features two violin soloists in a perfectly crafted 21st century tip of the hat to Vivaldi, Bach et al. The second movement’s simple instruction, quarter note = 60, indicates its dirge-like tempo and temperament, offering solo and chamber ensemble moments to a unique combination of four soloists - cello, trumpet, trombone, and horn - a fascinating timbral cocktail.

The third movement, dotted quarter note = +128, gives florid compositional attention to the principal flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon chairs with various solo and chamber music combinations. Flighty and fun, its pleasant tune flows through the wind soloists and orchestral accompaniment like a rolling wave. The fourth and last movement of Concerto Grosso, Finale, brings all ten soloists together for what the composer described on stage before the premiere in 2013 as a “Stravinsky pep, that just keeps it running through to the end.”

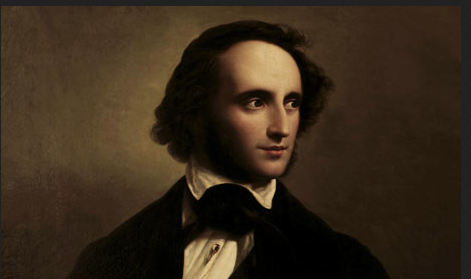

With his appointment as conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1835 composer, pianist, organist, editor, and conductor Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), threw himself into the musical life of the town, founding its music conservatory, editing the prestigious Leipzig music journal, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, conducting at the city’s opera house, and championing the music of Schubert and Schumann. Little wonder he died young there, at the age of 38.

Contemplating composing his first violin concerto after consultations with his Gewandhaus Orchestra concertmaster, Ferdinand David, Mendelssohn initially sketched out in 1838 what would become his Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64, finally premiering the multiply revised final product with the orchestra and David as soloist in 1845 – two years before the composer’s early passing. The Violin Concerto was an instant success with the public and violin virtuosi alike, remaining at the top of the repertoire, to this day.

Bubbling for the most part with Puckish jollity and lightheartedness – a fascinating echo of the energy and optimism of his incidental music three years earlier to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1842), the Violin Concerto, his last composition in the concerto genre, is also reflective and subtly enigmatic. While the Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream is in E Major, a jolly key, two years on, Mendelssohn needed E minor as the expressive tonal nimbus for his Violin Concerto; a musical metaphor perhaps, for his increasingly fragile psychological as well as physical health toward the end of his life.

The first movement, Allegro molto appassionato has the soloist playing with the orchestra from the very first bars, an innovation that must have excited audiences at the time, as it still does today. A gorgeous melody, tempered in moody reflection with a touch of ironic sadness, comes and goes between recurrent bursts of cheerful energy. A final, nearly manic cadenza before a last romantic interlude, is followed by a speed fest of virtuoso writing for orchestra and soloist that brings the movement to an exhilarating close.

The slow movement, Andante – Allegro non troppo, is the cipher that discloses a deeper story. A lonely solo bassoon tone is suspended in the silence between first and second movements, a prescient umbilical connection of emotional subtexts, and an eerily and completely unique musical special effect. A gorgeous, somewhat yearning waltz-like tune begins the movement with compelling certainty. Surges of romantic sighs prepare the scene for increasingly passionate ascending sequences from the soloist, answered in-kind by the orchestra. The movement settles finally, into a Peaceable Kingdom of exhausted calm.

The last movement Allegro molto vivace opens with a few lingering dramatic sighs from the earlier movement, before a martial but elegant brass fanfare announces a new quadrille and with it, a return to the lively pace and frolicsome charm inspired by the composer’s early music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The concerto ends in a hail of virtuoso solo fiddling and orchestral brilliance.

Russian-born violinist Philippe Quint (1974-) studied at the Special Music School for the Gifted in Moscow, making his debut as a concerto soloist at the age of nine. Immigrating to the United States in 1991 to study at The Juilliard School, Quint earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees there. He is now an American citizen. Philippe Quint has appeared with orchestras around the world, including his appearance with the Santa Barbara Symphony in 2017 playing Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, and Astor Piazzolla’s, The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires. The artist plays a 1708 “Ruby” Antonio Stradivari violin, a loan from the Stradivari Society, a philanthropic organization based in Chicago.

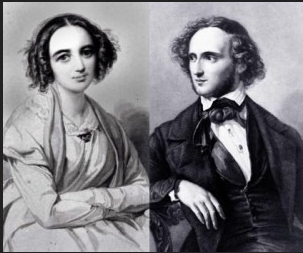

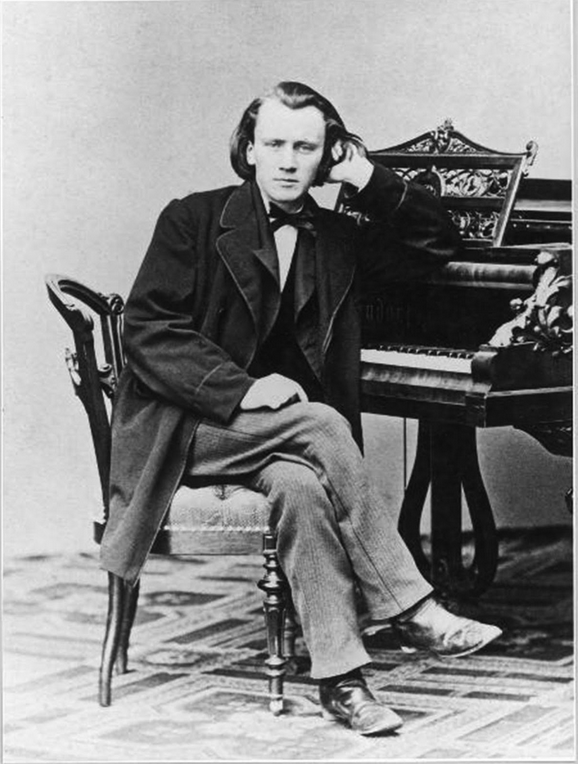

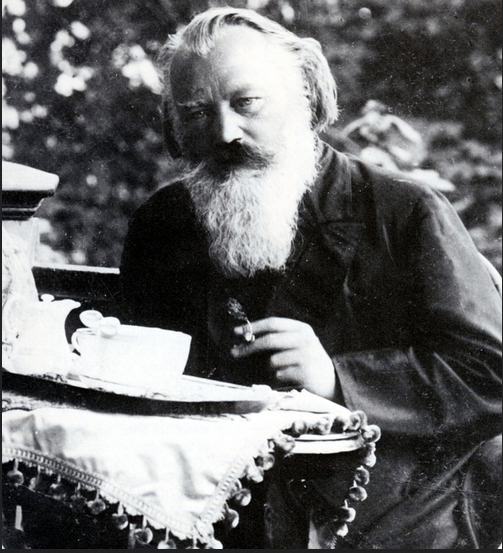

For Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) the 1850’s, when he was in his late teens and early 20’s, were fraught with passion, rejection, and self-doubt. The young genius ran with an impressive crowd, including Felix Mendelssohn, and Clara and Robert Schumann among others. Falling hopelessly in love with Clara, Brahms even moved in with the Schumann family to help with their growing flock of children and Robert’s increasing mental instability; a ruse of course on Brahms’ part, to be closer to the source of his lifelong infatuation. Clara, grateful for the handsome young Brahms’ support, nevertheless was quite clear with him about the impossibility of a more intimate relationship.

Brahms began sketches for his Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 in 1854, just two years before Robert Schumann’s death at age 46 in 1856, and after an earlier attempt at a symphony that morphed into his Piano Concerto No. 1, in D minor, Op. 15 (1858). It took the composer another 22 years of revisions, re-writes, doubt, and hesitancy, before he allowed a first performance of the Symphony No. 1 in 1876.

While Mendelssohn’s seven-year long Violin Concerto project can be comfortably attributed to the composer’s practical desire to create a virtuoso masterpiece for the ages (he succeeded), Brahms’ several re-writes and delays in finishing and finally producing his sometimes troubling and arduous, ultimately triumphant Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68, are more difficult to decode.

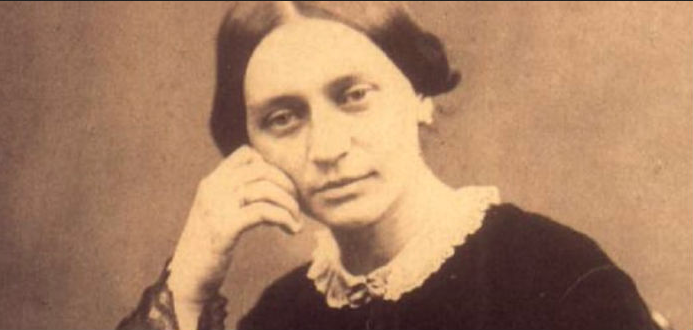

Clara Schumann looms large as the secret emotional backstory for this work; a gossamer and reticent presence to be sure yet possessing a powerfully intoxicating intellectual and sexual attraction for the composer. After Schumann’s death, Clara remained a widow for the rest of her life, as the Victorian age dictated. Brahms too, remained single, his passions and disappointments expressed in his music.

With its harsh opening bars and insistently pounding fate rhythm on timpani, the first movement, Un poco sostenuto – Allegro, begins in a state of catastrophic predilection. There are eye-of-the-storm calms in an otherwise anxious first movement, but a building wave of orchestral sighs regenerates the tempest, time and again. Finally, in exhausted resignation, the movement an enormous, nearly stand-alone tone poem on romantic angst, settles like the Titanic at the nadir of its plunge, in dark, uneasy quiet.

Nothing short of a love song, the second movement, Andante sostenuto, is a prayer of longing that builds to an ecstatic, bittersweet-tinged soliloquy of adoration and unrequited love. Near the end of the movement, a horn and fiddle duo of nearly unbearable delicacy like the movement itself, is one of the tenderest accounts of heartbreak in the repertoire.

A leisurely walk in the woods is the opening imagery of the third movement, Un poco allegretto e grazioso, a mood that eventually morphs phoenix-like through several orchestral sighs toward a noble theme of magnificent breadth and optimism, then back to the woodland idyll of the beginning of the movement, this time slightly tinged in subtle apprehension, preparing the listener for the dramatic emotional opening section of the last movement, Adagio – Più andante – Allegro non troppo, ma con brio – Più allegro.

The movement’s long title indicates the sturm und drang of its several moody episodes, but with the introduction of the main theme in strings, Brahms announces a change of psyche, the beginning of an orchestral tsunami of spiritual triumph that reaches its ecstatic peak with the introduction of a stunning brass choir tune that propels the movement to its hair-raising final bars.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

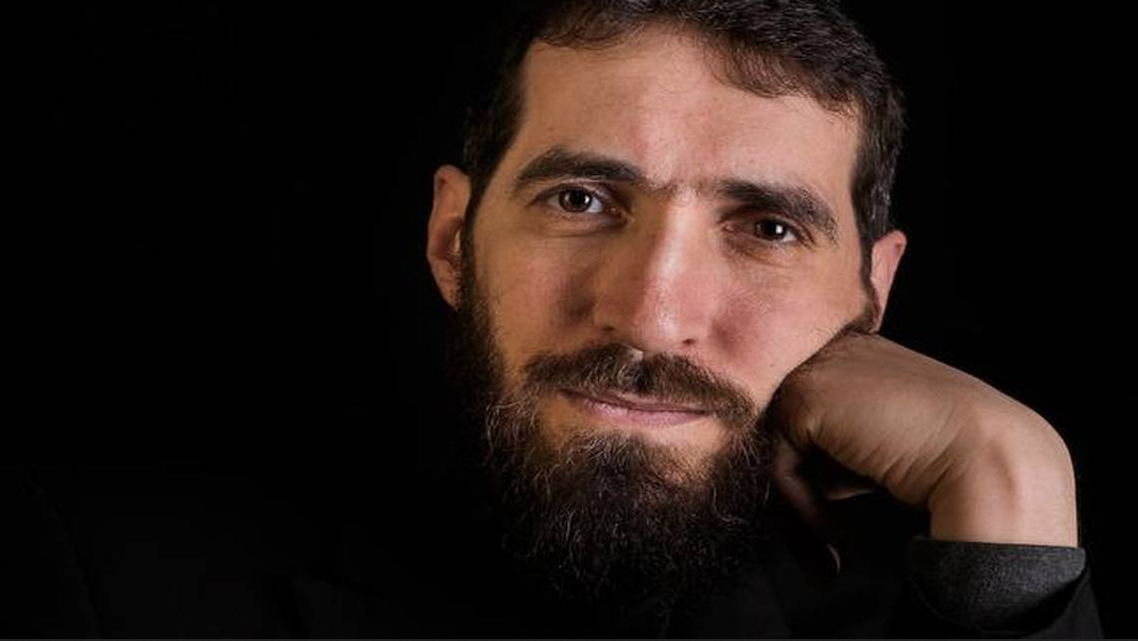

Conductor Nir Kabaretti

Download a PDF of the program notes

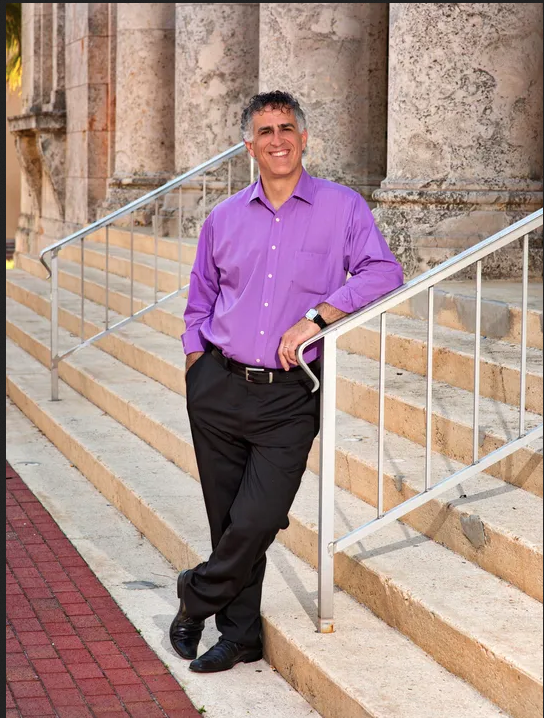

American composer Jonathan Leshnoff

Violinist Philippe Quint

Violinist Philippe Quint | VC 20 Questions Interview

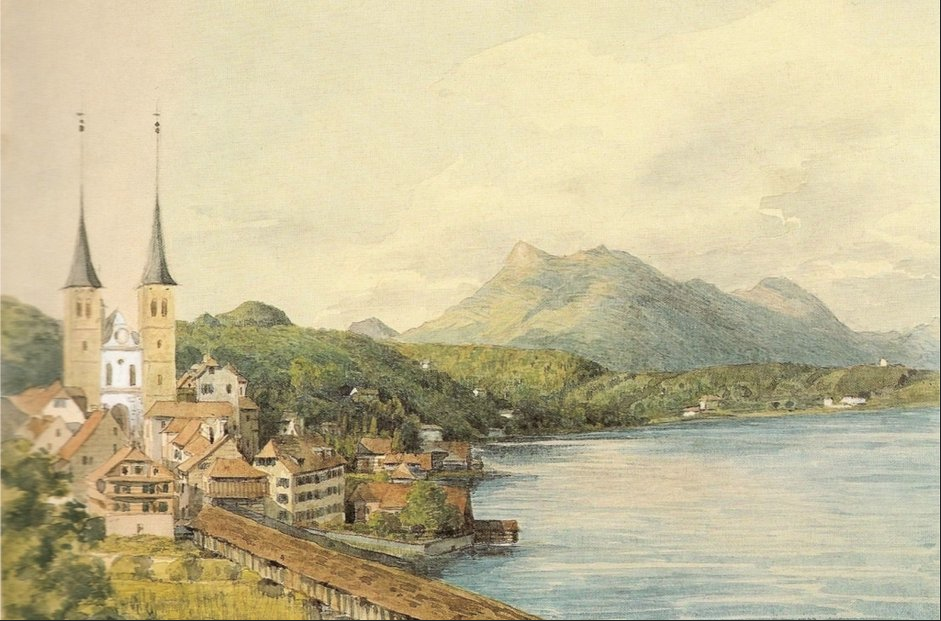

Mendelssohn's watercolor View of Lucerne

Felix Mendelssohn

Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn

Johannes Brahms in his 20s

Robert and Clara Schumann

Clara Schumann never remarried after Robert Schumann's death

Brahms remained single the rest of his life