Santa Barbara Symphony program notes April 15-16 2023: Beethoven Dreams

Visit the Santa Barbara Symphony

Visit conductor Nir Kabaretti’s website

Visit composer Ella Milch-Sheriff’s website

Visit Santa Barbara’s Ensemble Theatre Company website

Read my review of the April 15 2023 concert

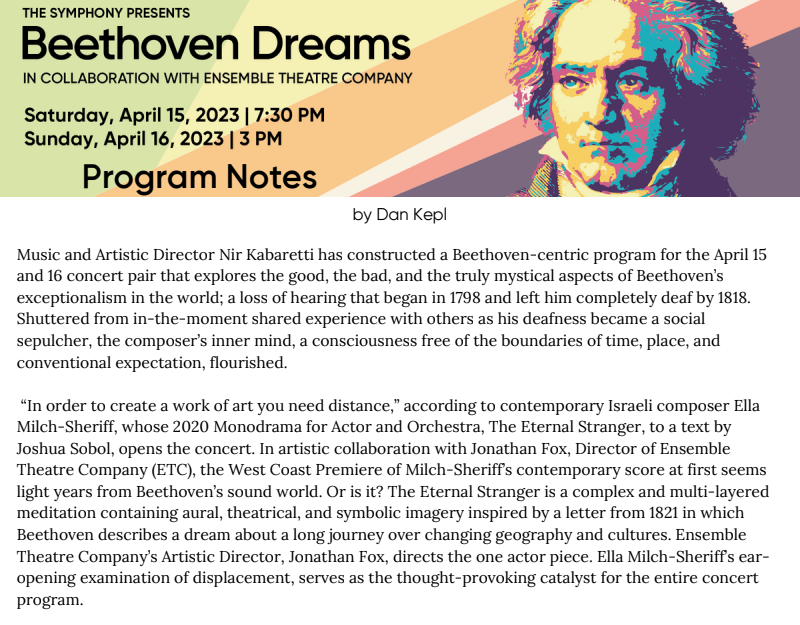

Beethoven Dreams

Music and Artistic Director Nir Kabaretti has constructed a Beethoven-centric program for the April 15 and 16 concert pair that explores the good, the bad, and the truly mystical aspects of Beethoven’s exceptionalism in the world; a loss of hearing that began in 1798 and left him completely deaf by 1818. Shuttered from in-the-moment shared experience with others as his deafness became a social sepulcher, the composer’s inner mind, a consciousness free of the boundaries of time, place, and conventional expectation, flourished.

“In order to create a work of art you need distance,” according to contemporary Israeli composer Ella Milch-Sheriff, whose 2020 Monodrama for Actor and Orchestra: The Eternal Stranger, to a text by Joshua Sobol, opens the concert. In artistic collaboration with Santa Barbara’s Ensemble Theatre Company (ETC), the West Coast Premiere of Milch-Sheriff’s contemporary score at first seems light years from Beethoven’s sound world. Or is it?

The Eternal Stranger is a complex and multi-layered meditation containing aural, theatrical, and symbolic imagery inspired by a letter from 1821 in which Beethoven describes a dream about a long journey over changing geography and cultures. Ensemble Theatre Company’s Artistic Director, Jonathan Fox, directs the two actor narrative. Ella Milch-Sheriff’s ear-opening examination of displacement serves as the thought-provoking catalyst for the entire concert program.

A delicate thread of unusual tonal continuity links present and past; Milch-Sheriff’s mystical Beethovenian journey, and the next two Beethoven works maestro Kabaretti has chosen for this program, both composed during a burst of creative energy in 1805 and 1806. The Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 (1805-1806), with guest artist, pianist Inna Faliks, and the sunny Symphony No. 4 in Bb Major, Op. 60 (1806) express poignantly, Beethoven’s continued optimism in the face of a soul-crushing reality.

By 1821 Beethoven, now totally deaf and communicating with visitors by exchanging written notes, slipped deeper into an inner world of private thought and subconscious creativity. A stranger for the rest of his life except in memory, to the sounds and interactions of the outside world which for him had gone completely silent, he wrote his friend and publisher Tobias Haslinger on September 10, 1821, a letter that remained mostly unknown to biographers until recently.

Beethoven describes a dream about a very long journey “as far even as Syria, as far even as India, as far even as Arabia,” culminating at Jerusalem, where his friend the publisher greets him with an epiphanic but secret revelation. Beethoven includes a hastily sketched musical sequence in contrapuntal canon form, a dream-inspired conscious afterthought Ella Milch-Sheriff references subtly in The Eternal Stranger.

Israeli composer Ella Milch-Sheriff was commissioned by conductor Omer Meir Wellber in 2019 to compose a work commemorating Beethoven’s 250th birthday the following year. Empathizing with the composer’s increasing isolation from society because of deafness, searching for a contemporary text that might express that loneliness, Milch-Sheriff quickly discovered Israeli playwright and author Joshua Sobol’s poem, The Eternal Stranger, inspired by Beethoven’s mysterious dream letter from 1821.

“Whenever I compose for text, I become identified with its content - it becomes me,” Milch-Sheriff writes. “This work is about a stranger, a refugee, or any other person in a hostile environment with no legitimate reason to be rejected but the fact that they are different, look different, move differently, speak differently.” Milch-Sheriff continues. “The Beethoven dream letter and Joshua Sobol’s poem enabled me to use vast musical connotations from my home country of Israel and the sounds of my childhood; a mixture of Arabic music, Jewish music of all kinds (eastern and western) as well as the music of the old European world.”

With an Ensemble Theatre Company actor in silent, motionless repose on stage (Beethoven dreaming?) The Eternal Stranger begins in a mist of atavistic sonic mystery; low string and wind rumble under high string harmonics create a mood of spooky divination. As the score becomes more colorful, with oboe and bassoon narratives and denser wind/brass textures, the sleeper awakens and begins to move about the stage, reciting Joshua Sobol’s first stanza: “On a shore where a wave from the stormy ocean tossed him. Seeking to grasp the ways of the people there, the masters of the land. They take him for a misanthrope. He can see it . . . by the looks in their eyes.”

A waltz-like section, increasingly frenzied, colors the narrator’s response: “I am not a misanthrope! On the contrary! I love people, I also love animals, plants, and the woods; All of nature.” A new section, an ironically fateful and darkly orchestrated march to Sobol’s words, “My mother’s language is buried in me. Her voice in quietude is calling to me,” produces The Eternal Stranger’s musical apotheosis; a flash of emotionally paralyzing high string angst, followed by an uncanny calm, the narrator reacting to the event with his only prop, a hand drum, “Letting the dead people be resurrected in a dream!” Finally, a brief but terrifying orchestral maelstrom, fabulously conceived and magnificently orchestrated by the composer, explodes then dies away to the final words, as also at the beginning of the narrative, “A man is observing people . . .”

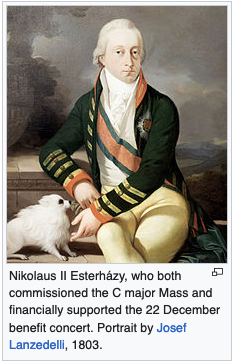

Whether in cahoots with the composer, or simply as the result of a novel personal programming notion, conductor Omer Meir Wellber, who commissioned The Eternal Stranger, chose to link without break Milch-Sheriff’s work to Beethoven’s Mass in C Major for a video performance at Teatro Massimo in Palermo: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMQVk4ZZtHA – a marvelous artistic maneuver that bonded nineteenth century Beethoven to the twenty-first century, exactly the purpose of composer Ella Milch-Sheriff’s Monodrama. For the West Coast premiere of The Eternal Stranger in Santa Barbara, the last bar segues directly as well, this time to the solo piano passage that opens Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4.

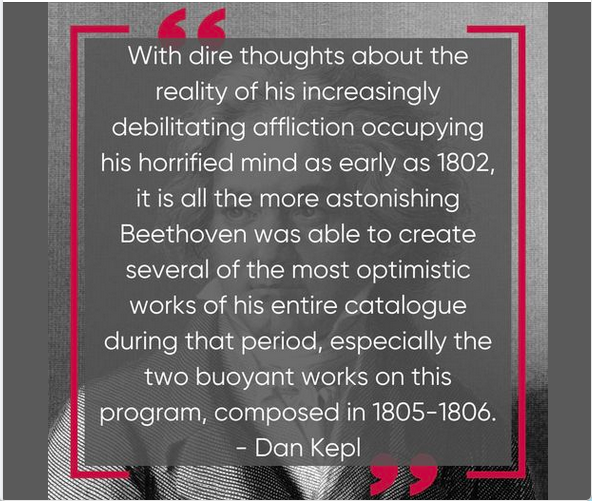

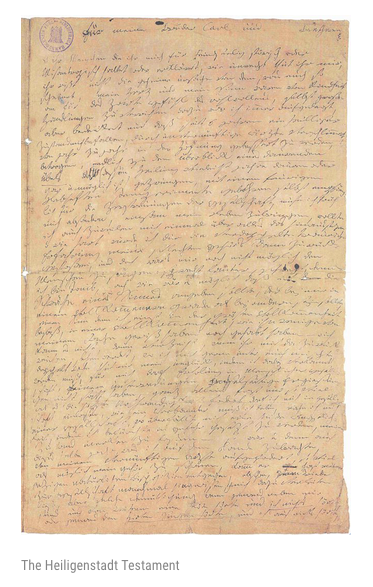

Dated 6 October 1802 and referred to by historians as the Heiligenstadt testament, Beethoven (1770-1827) penned a note to himself he kept secret the rest of his life – a stream of consciousness rant about his agony at being so offhandedly misunderstood because of his hearing loss, which he managed to keep secret for several years. It reads in part: "O you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you.” With dire thoughts about the reality of his increasingly debilitating affliction occupying his horrified mind as early as 1802, it is all the more astonishing Beethoven was able to create several of the most optimistic works of his entire catalogue during that period, especially the two buoyant works on this program, composed in 1805-1806.

The Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 (1805-1806) was premiered in Vienna in 1808, as the Napoleonic Wars were beginning to tear Europe to pieces. The composer, not yet totally incapacitated by his hearing loss, was able to function as piano soloist for the concerto’s debut. The first movement, Allegro moderato, is unique and visionary, from its quiet opening solo piano statement, echoed softly by the orchestra, to the extended orchestral section immediately after, the pianist remaining still during that section before the two protagonists engage each other in narrative, their various virtuoso musical jousts and cadenzas choreographed carefully by the composer.

The second movement, Andante con moto, with its forceful, even sternly judgmental opening orchestral sequences, the piano a meek supplicant in response to each, eventually yields to the piano’s more eloquent plea for calm and reason. The admonition motive diminishing, emotions ebb and flow. Reveries and sighs, both orchestral and in solo piano, suggest struggle and denial. The movement reaches exhausted resignation, then segues Guignol-like, into an off-the-string orchestral gallop that erases all previous doubt, and presents the third movement, Rondo vivace, at a jolly pace. Bravura exchanges between soloist and orchestra embellish the thematic material cleverly, Beethoven squeezing every drop of developmental possibility from his tunes – a triumph of compositional invention and colorful orchestration.

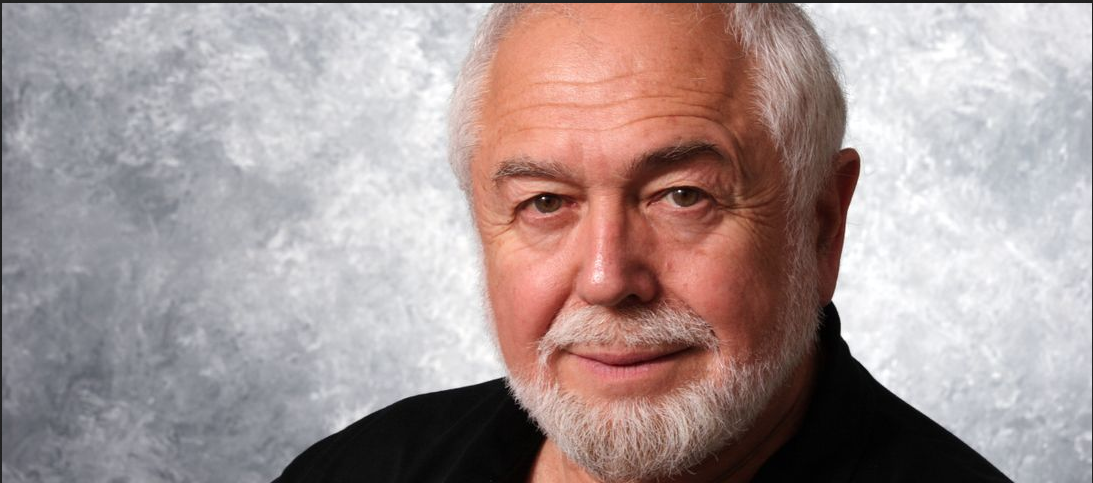

Ukrainian-born pianist Inna Faliks is Professor and Head of Piano at UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. “Adventurous and passionate” (The New Yorker), she has established herself as one of the most exciting, committed, communicative, and poetic artists of her generation, a champion of the standard repertoire as well as genre-bending interdisciplinary projects by contemporary composers. A writer as well as world-traveling concert pianist, Inna Faliks’ musical memoir, Weight in the Fingertips was published in 2023.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in Bb Major, Op. 60 (1806) was premiered in Vienna in 1808 on the same four-hour long program as his Piano Concerto No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, and the Choral Fantasy – a gala benefit concert on behalf of the composer.

Mixed reviews greeted the Symphony No. 4. It’s first movement, Adagio – Allegro vivace, clearly an homage in structure at least to the opening sections of Haydn’s late symphonies, its slow introduction inching hesitantly toward a sudden tidal wave of vigorous energy and change of mood, may have seemed a bit old fashioned to the audience. Nevertheless, the Allegro vivace section is one of the most inventive in the symphonic repertoire; bright and youthful, with unpretentious dollops of happiness – a sparkling musical jewel.

The second movement, Adagio, which Hector Berlioz declared to be the work of the Archangel Michael, is a strangely awkward lullaby, its odd and emphatically repetitive dotted rhythmic figure morphing over time and compositional development into a noble hymn - courage in the face of adversity? The last bars settle into the sound imagery of a woodland idyll akin to the ambiance of the Symphony No. 6, Pastorale (1808); a fond memory of the composer’s many happy walks in the German countryside, whose intimate sounds would soon be lost forever to his ears.

If the first stage of grief is denial, the years from Beethoven’s hearing loss diagnosis (1798) to his Vienna benefit concert in 1808 might arguably represent this first phase of the composer’s seven-stage grieving process over hearing loss. Interestingly, his compositions during this span of years, despite debilitating prescience about the inevitability of the future, are disarmingly optimistic, full of energy, innovation, color, and heroic valor. Denial? Cover up? Whatever the motives behind these compositions, subconscious or otherwise, they all speak magnificently to the composer’s resolve in the face of adversity.

The two last movements of the Symphony No. 4, Menuetto – Allegro vivace, and Allegro ma non troppo, are the musical embodiment of youthful hope, resilience, and vigor. Playfulness is king-of-the-mountain in both movements, but particularly the last, which begins at a thrilling tempo, then barrels forward with additional breathtaking speed and energy. Clever compositional nods to Haydn – Mannheim rockets, coy rhythmic and harmonic dodges – charge this happy musical cyclone toward a full throttle finish, notwithstanding one last sneaky Haydnesque deception just before the sudden and much faster last few bars. Out of adversity, strength!

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Download a PDF of the program notes

Composer Ella Milch-Sheriff

Beethoven's publisher Tobias Hasliger to whom he wrote about his mysterious dream in 1821

Santa Barbara Ensemble Theatre Company Artistic Director Jonathan Fox

Joshua Sobol, Israeli playwright and author of The Eternal Stranger

Download a PDF of Joshua Sobol’s text to The Eternal Stranger

Conductor Nir Kabaretti

Pianist Inna Faliks

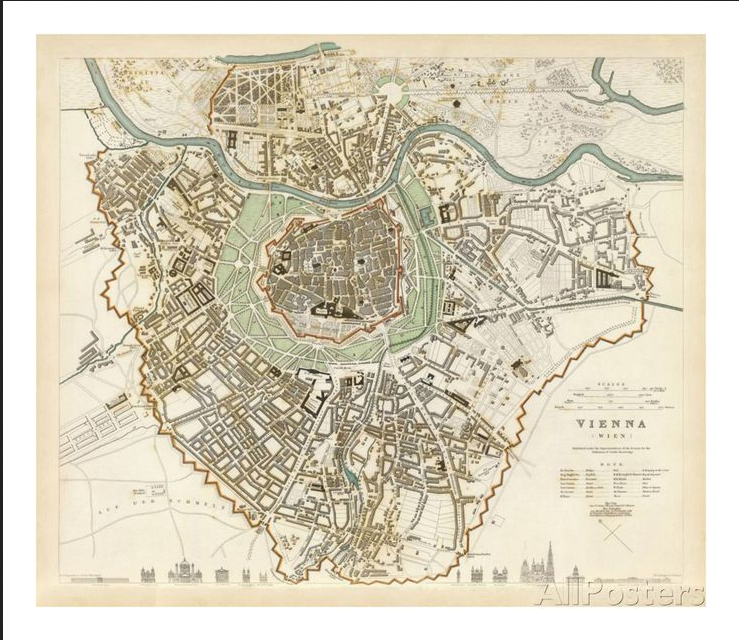

Map of Vienna circa 1808

Theater an der Wien where the December 22 1808 four-hour long gala benefit concert for Beethoven took place