Your Custom Text Here

Read Harvey Thurmer’s biography

Visit Miami University College of Creative Arts

Read my review of Thurmer’s recording of György Kurtág’s Kafka Fragmente, Opus 24

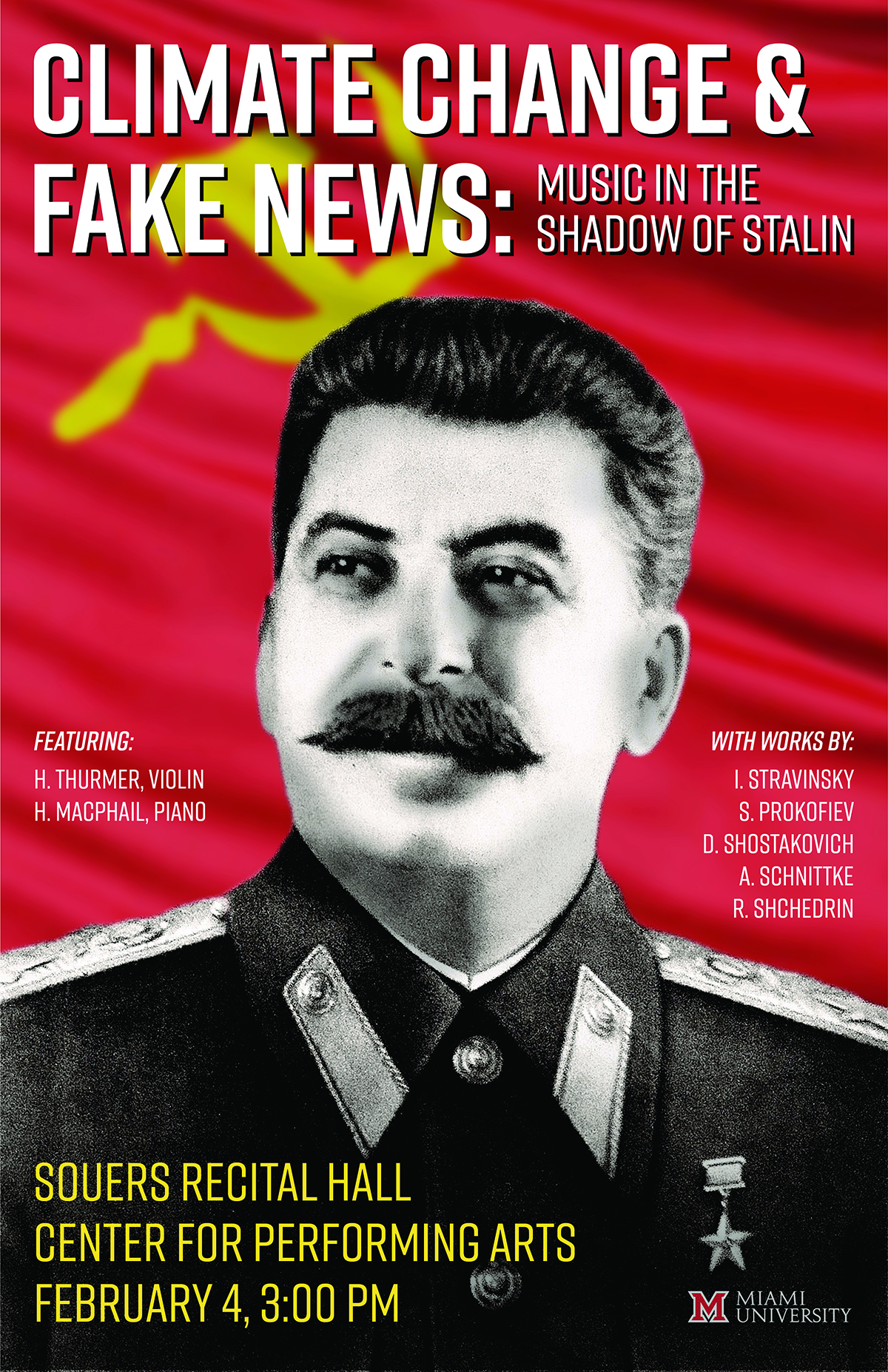

Violinist Harvey Thurmer, New England Conservatory grad and a member of the string faculty at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio presented a fascinating and all too relevant lecture recital at Souers Recital Hall on the MU campus February 4th 2018 which illuminated tellingly, the double-edged sword of life for creative artists in a totalitarian state. With collaborative pianist Heather McPhail Thurmer presented a program titled Climate Change & Fake News: Music in the Shadow of Stalin; powerful musical examples by Russian composers Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Schnittke and Shchedrin of truth speaking to power - carefully.

With immaculate musical taste and necessary historical backstory between pieces, Thurmer began his program with Stravinsky’s Pastorale (1907). Clearly a nostalgic chestnut from the composer’s youth in Imperial Russia before the Revolution, Harvey played this accidental memoir of a happier time with melancholic warmth. Prokofiev’s Solo Sonata, Opus 115 (1947) followed in similar though more haunted, post-WW II character. A treat because it is not often performed, the Opus 115 is an homage to Bach in some ways, full of cheerful counterpoint and devil-may-care insouciance. Liberated from the printed page by Thurmer’s clear understanding of color and imagery, enhanced by the violinist’s expert articulation and finely honed intonation, spiced with a soupçon of Russian gemütlichkeit, the sonata is guardedly optimistic in an otherwise ashen post-war landscape.

Thurmer makes clear in his chat from the stage the next piece, Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata No. 1, Opus 80 (1938-46), has quite a different story to tell. Wary is the overall feeling of this sonata as Stalin’s increasingly ruthless treatment of his own people, especially intellectuals, made silence a survival tactic during the timeframe of its composition. Musically haunting, this sonata does not dare speak to power, instead illuminating totalitarianism, intolerance and oppression in graphic tonality and stunning subtext. Thurmer and McPhail pulled out all the stops on this one — colors deep as the subconscious, beautiful as black sapphire; quiet, treacherously difficult but powerful whisper runs on fiddle; spine-chilling journeys down harmonic pathways as obtuse as guessing friends from enemies must have been at the time. A powerful performance by both artists.

Shostakovich’s Preludes Opus 34, No. 10, 16, 24 (1931-33) arranged by Dimitri Tziganov, offered narrative opportunity with every note of Thurmer’s interpretation: wistful, tenuous, intuitive. Schnittke’s First Sonata (1963) performed by Thurmer and McPhail with intense emotional focus and mystical result, together with Rodion Shchedrin’s In the Style of Albeniz (1973), music by the Lenin Prize-winner that for all its Iberian pretense is unnervingly paranoid, macabre and acidic, rounded out the Climate Change & Fake News program, reminding the listener that despite the appalling psychological insult of thugs like Stalin on the creative spirit, art does in the end, triumph.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Read Harvey Thurmer’s biography

Visit Miami University College of Creative Arts

Read my review of Thurmer’s recording of György Kurtág’s Kafka Fragmente, Opus 24

Violinist Harvey Thurmer, New England Conservatory grad and a member of the string faculty at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio presented a fascinating and all too relevant lecture recital at Souers Recital Hall on the MU campus February 4th 2018 which illuminated tellingly, the double-edged sword of life for creative artists in a totalitarian state. With collaborative pianist Heather McPhail Thurmer presented a program titled Climate Change & Fake News: Music in the Shadow of Stalin; powerful musical examples by Russian composers Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Schnittke and Shchedrin of truth speaking to power - carefully.

With immaculate musical taste and necessary historical backstory between pieces, Thurmer began his program with Stravinsky’s Pastorale (1907). Clearly a nostalgic chestnut from the composer’s youth in Imperial Russia before the Revolution, Harvey played this accidental memoir of a happier time with melancholic warmth. Prokofiev’s Solo Sonata, Opus 115 (1947) followed in similar though more haunted, post-WW II character. A treat because it is not often performed, the Opus 115 is an homage to Bach in some ways, full of cheerful counterpoint and devil-may-care insouciance. Liberated from the printed page by Thurmer’s clear understanding of color and imagery, enhanced by the violinist’s expert articulation and finely honed intonation, spiced with a soupçon of Russian gemütlichkeit, the sonata is guardedly optimistic in an otherwise ashen post-war landscape.

Thurmer makes clear in his chat from the stage the next piece, Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata No. 1, Opus 80 (1938-46), has quite a different story to tell. Wary is the overall feeling of this sonata as Stalin’s increasingly ruthless treatment of his own people, especially intellectuals, made silence a survival tactic during the timeframe of its composition. Musically haunting, this sonata does not dare speak to power, instead illuminating totalitarianism, intolerance and oppression in graphic tonality and stunning subtext. Thurmer and McPhail pulled out all the stops on this one — colors deep as the subconscious, beautiful as black sapphire; quiet, treacherously difficult but powerful whisper runs on fiddle; spine-chilling journeys down harmonic pathways as obtuse as guessing friends from enemies must have been at the time. A powerful performance by both artists.

Shostakovich’s Preludes Opus 34, No. 10, 16, 24 (1931-33) arranged by Dimitri Tziganov, offered narrative opportunity with every note of Thurmer’s interpretation: wistful, tenuous, intuitive. Schnittke’s First Sonata (1963) performed by Thurmer and McPhail with intense emotional focus and mystical result, together with Rodion Shchedrin’s In the Style of Albeniz (1973), music by the Lenin Prize-winner that for all its Iberian pretense is unnervingly paranoid, macabre and acidic, rounded out the Climate Change & Fake News program, reminding the listener that despite the appalling psychological insult of thugs like Stalin on the creative spirit, art does in the end, triumph.

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Daniel Kepl chats with violinist Harvey Thurmer

Stravinsky | Pastorale arr. Dushkin

Commentary 1 before solo prokofiev

Prokofiev | Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 115 | Moderato

Commentary 2 before prokofiev op 80

Prokofiev | Sonata op. 80 | Andante assai

Commentary 3 before Shostakovich

Shostakovich | Four Preludes arr. Tsyganov | No. 10, 16, 24

Commentary 4 before Schnittke

Schnittke | Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano | Allegretto, Largo

Commentary 5 before Shchedrin

Shchedrin | "In the Style of Albeniz", for Violin and Piano | Con Passione

Read my review of Thurmer’s 2003 recording of György Kurtág’s Kafka Fragmente, Opus 24