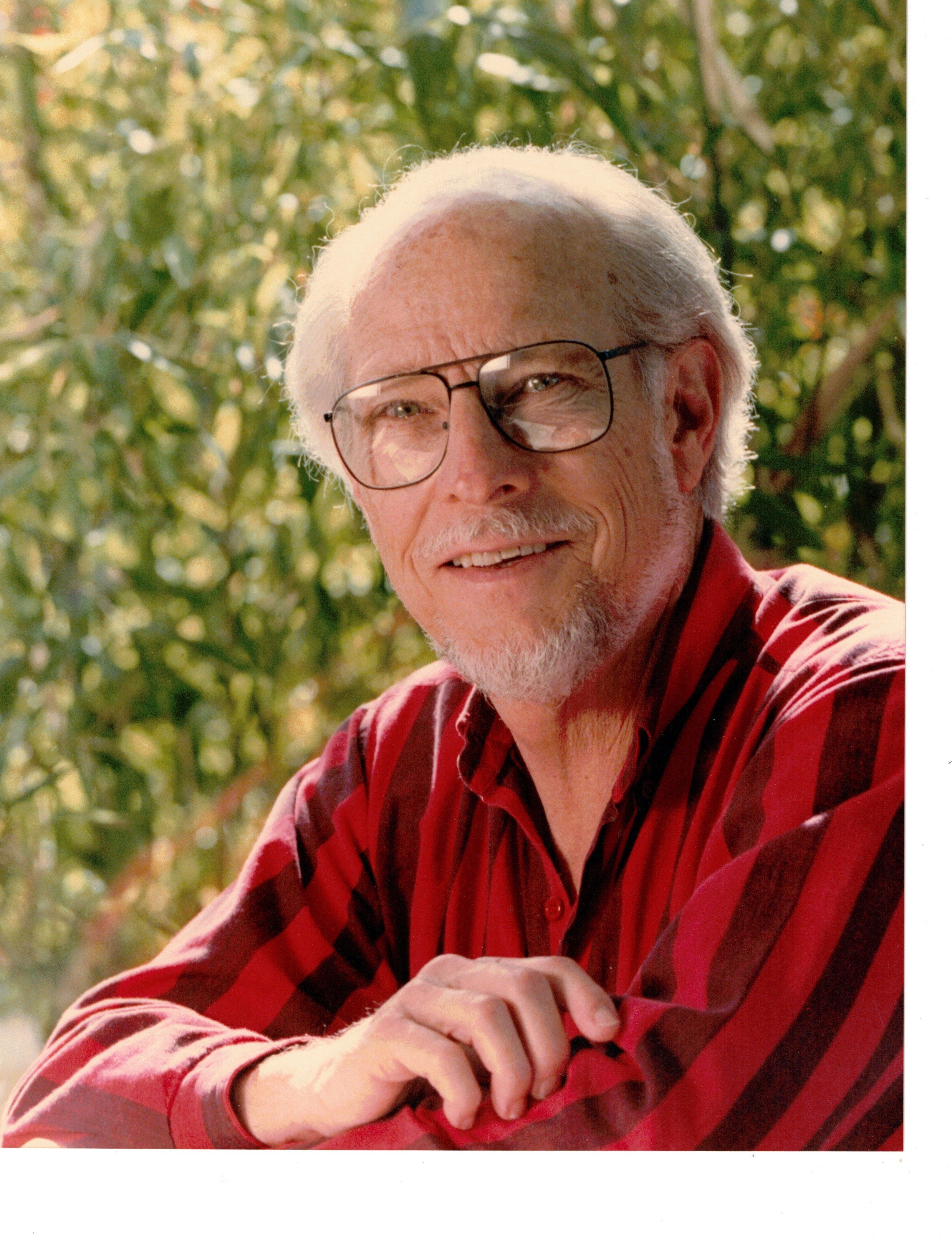

A CHAT WITH AMERICAN COMPOSER JOHN BIGGS, 90 IN 2022, ABOUT HIS CAREER, HIS MUSIC

Read a brief biography of American composer John Biggs

A catalogue of John Biggs’ discography

The complete Consort Press catalogue of John Biggs’ music

American composer John Biggs invited me to his 90th birthday celebration concert in October, 2022. I had attended his 80th birthday event in the same Ventura (California) venue a decade earlier. Both concerts, then and in 2022, featured a wide variety of Biggs’ chamber works, including new pieces he composed for each ten-year milestone.

The ambiance on both occasions was of friendship and sharing. Professional musicians, including members of the extended Biggs family, played his music together wonderfully, and with palpable fondness.

“Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter.” ― Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

I hitched a ride from Santa Barbara to Biggs’ 90th birthday concert with a professional cellist recently retired, who had enjoyed a substantial career playing in orchestras throughout the Bay Area, and has known the composer for decades.

During the 40 minute drive we discussed in particular, the Cello Sonata to be heard that afternoon, with its gorgeous slow movement, Larghetto. The secondary discussion going on silently in my mind was about Biggs’ lyricism in general - passé, or de rigueur?

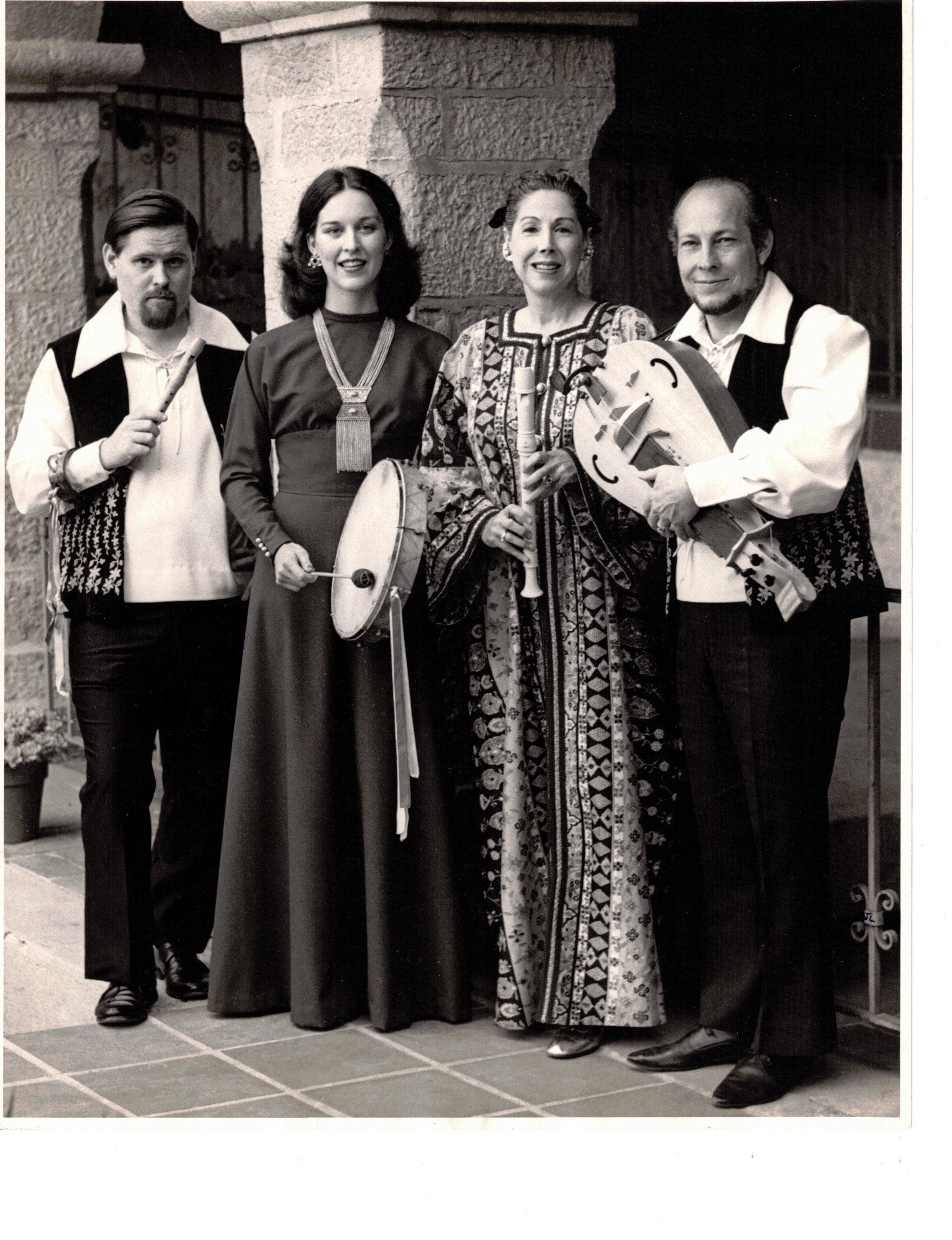

I met John Biggs for the first time around 1969-1970, when I interviewed him for a long forgotten - I certainly don’t remember a word of the piece - article for the Santa Barbara News-Press. I was 21 or thereabouts, Biggs was living in Santa Barbara with his wife at that time, soprano Salli Terri.

They were in the middle of a California Mission Music project and tour, the John Biggs Consort performing works composed expressly for the California mission system and its musical needs; masses, antiphons, preludes, postludes and the like.

Works by Spanish, but also New World composers of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, who were active in California in those days, were thoroughly researched - resurrected is a better word - and performed by the John Biggs Consort, often for the first time since the 1780s.

Soon after that interview, I began my professional career as a conductor, training at the California Institute of the Arts and Trinity College of Music, London, which led to gigs in Seattle for a decade or more, conducting for Seattle Festival Ballet, Seattle Wind Ensemble, and Seattle Debut Orchestra. Wearing my hat as an entrepreneur, I also brought the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival to Seattle during the summers of 1979 and 1980. In short, I lost touch with southern California and John Biggs.

Back in Santa Barbara in the early 1980s, it wasn’t long before I was having a serious look once again at Biggs’ music, in particular his Symphony No. 2, which I contemplated conducting with the American Collegiate Symphony in London in 2003.

Biggs and I reconnected, and I have had an opportunity since, to see and review performances of his opera Ernest Worthing, based on Oscar Wilde’s play, The Importance of Being Ernest, and the Symphony No. 2, among other works performed in recent years in his new sphere of musical influence, Ventura/Ojai. Hats off to Ventura College, for championing Biggs’ works.

The premiere of Biggs’ Concerto for Violin and Classical Orchestra, which took place in Santa Barbara in the 1990’s, violinist Nina Bodnar whom I’d known since she was nine (!) having just returned to Santa Barbara after a stint as concertmaster of the Saint Louis Symphony (1989-1995), found me eavesdropping at the dress rehearsal before the debut.

The beauty of the quiet tête-à-tête between composer and soloist, was watching John Biggs allay Bodnar’s misapprehensions by example of his profound knowledge of the instrument. Nina Bodnar’s first experience with the new work became much more comprehensible for her as a result. A delight to watch the exchange, I listened and learned. The beauty of Biggs’ confidence in his musical vision was also an E-ticket to enlightenment about his craft.

The Second Symphony, which I know intimately from a conductor’s point of view is like all of Biggs’ works, unmistakably American, influenced at some deep, internal level by uniquely personal sonic structures and harmonic language - his own voice - molded and shaped by several mentors and colleagues: Stravinsky, Copland, Sessions, Piston, Diamond, Bernstein, Creston, Persichetti, Dahl, Harrison et al.

I reviewed the Santa Barbara Symphony premiere some years back (Betty Oberacker was piano soloist and later recorded the work) of Biggs’ Variations on a Theme of Shostakovich for Piano and Orchestra, and have listened to much of his chamber music output over the years as well, while considering repertoire for the Santa Barbara Chamber Music Festival (2003-2008), which featured American music exclusively.

All of us in professional classical music and other intellectual art forms, know very well the continuous struggle to be seen, heard, or read; the perennial contest between pulp fiction and literature, popular music and art music, works of substantive visual effect, and wallpaper. It’s a lifetime hustle in a world that is hellbent on cultural illiteracy. John Biggs is no stranger at 90 to that struggle,and his thoughts on the future of the arts, while sobering, sound a necessary warning.

“Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you! Let nothing be lost upon you. Be always searching for new sensations. Be afraid of nothing.” ― Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

Daniel Kepl | Performing Arts Review

Daniel Kepl chats with American composer John biggs, who was 90 in 2022

SANTA CLARA RIVER

Symphony No. 2

The John Biggs Consort

Variations on a Theme of Shostakovich (USA)

BIGGS Larghetto

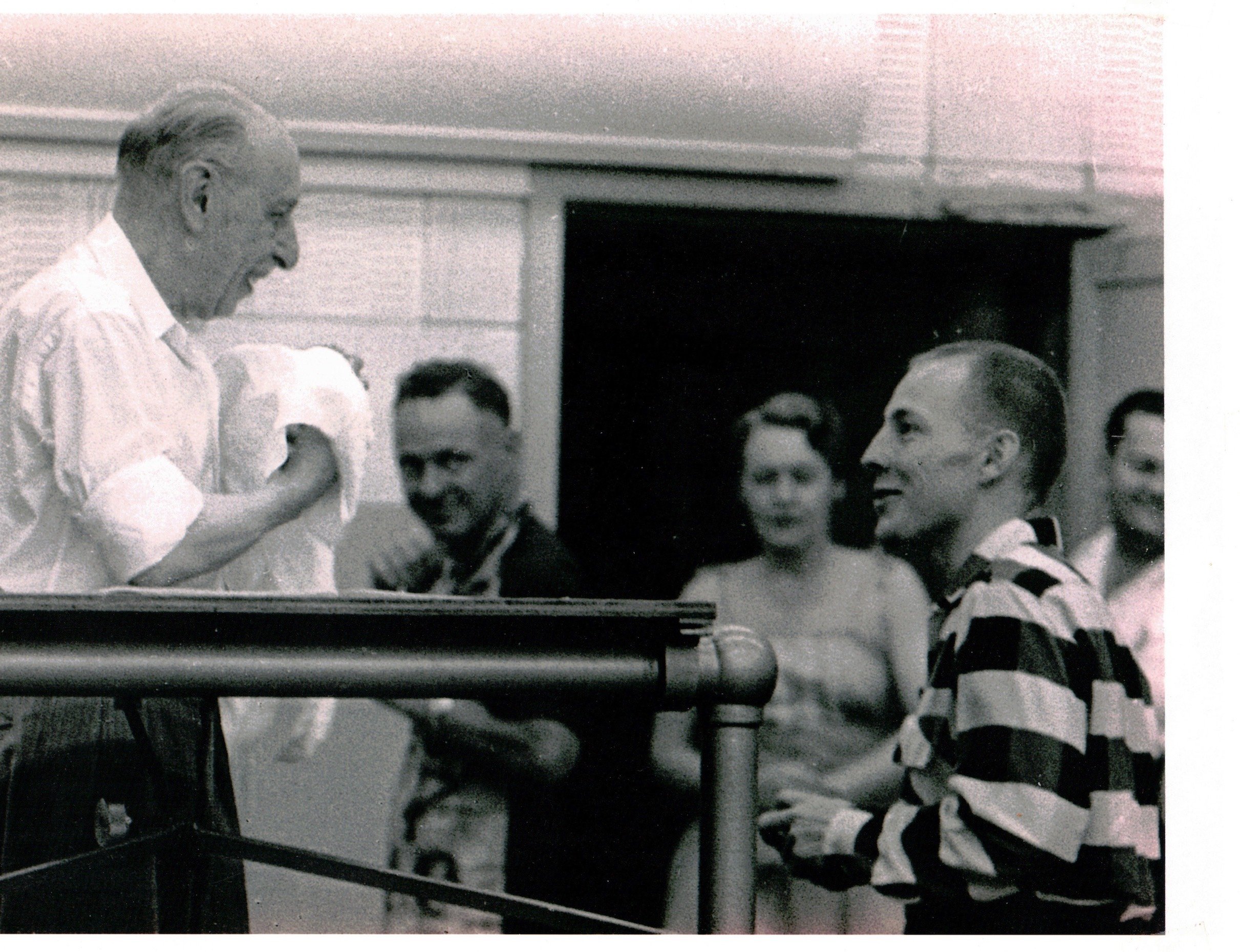

Composer Igor Stravinsky meets John Biggs

InventionForViola